| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

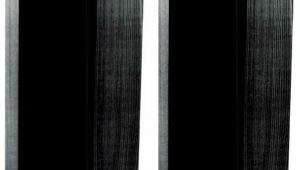

Hales Design Group Concept Five loudspeaker Page 3

Part of this can be attributed to the fact that the Five's tonal balance is intrinsically lean. Paradoxically, this leanness is not associated with a lack of extension—the Concept Five does reproduce well down into deep bass territory. Paul Hales may very well be right that many listeners, myself included, have become used to the excess bass resonant energy he attributes to bass-reflex enclosures, but I'm not just comparing the Fives to other speakers. I am not unfamiliar with live music, and one of the most seductive qualities of live sound is that sense of slam in the lower octaves that is more physical than aural. You could almost call the Concept Fives a cerebral speaker. They sure aren't earthy, rich, elemental, Zorba-like. No, they're more like Zorba's English employer—clear on everything, but stiff and a tad removed.

Footnote 1: Interestingly, after a day buried in Grove and Meyer and Cooper's The Rhythmic Structure of Music, the article that got closest to the point was Martin Colloms's "Pace, Rhythm, and Timing," published in the November 1992 Stereophile, Vol.15 No.11, pp.76–97.

But more than that, I felt that the Fives didn't swing easily. That sounds vague, I realize—that's one reason I saved the point for last. "Swing" is all but indefinable. I know that because I spent a good part of today looking up definitions, in the hopes that they would help clarify my point. You want to hear from The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition?

"swing v 10 Music a To have a subtle, intuitively felt rhythm or sense of rhythm. b To play with a subtle, intuitively felt sense of rhythm."

How about The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, edited by Barry Kernfeld?

"(1) A quality attributed to jazz performance. Although basic to the perception and performance of jazz, swing has resisted concise definition or description. Most attempts at such refer to it as primarily a rhythmic phenomenon, resulting from the conflict between a fixed pulse and the wide variety of actual durations and accents that a jazz performer plays against that pulse. However, such a conflict alone does not necessarily produce swing, and a rhythm section may even play a simple fixed pulse with varied amounts or types of swing. Clearly other properties are also involved, of which one is probably the forward propulsion imparted to each note by a jazz player through manipulation of timbre, attack, vibrato, intonation, or other means; this combines with the proper rhythmic placement of each note to produce swing in a great variety of ways."

Does that help? The key point in every definition of swing that I came up with—and I'm sparing you several pages' worth—is that swing's essence is personal and not clearly definable.

So how can I criticize a speaker for lacking something I can't even define? Because we all know it when we experience it. Notice that the consensus is that swing is not that swing doesn't exist, but that it's resistant to definition (footnote 1).

I can point to a few examples. "The Lover," from Medeski, Martin & Wood's Friday Afternoon in the Universe (Gramavision GCD-79503), should move along with a sense of slam from Chris Wood's acoustic bass, augmented by John Medeski's growling B-3. Wood plays hard, and there's a lot of string slap and monster bottom end pushing the song along. The Hales' leanness robbed the piece of its sense of impact—where the bass seems to push against the organ and just butt the melody forward. However, I must also say that I have never heard the acoustic surrounding Billy Martin's drums better portrayed. The thing is, "The Lover" isn't about where Martin's drums were recorded, it's about the collision of a big, lumbering beat with a fat, greasy riff—colored by the drummer's skittering polyrhythms. I think you lose the song's soul...er, funk...er, soul when you reduce its essential elements.

Sonny Rollins's "St. Thomas" is another song that beguiles through its swinging—in this case, Caribbean—lilt. The melody ain't much, but it has lasted because of its rhythmic charm. When Joshua Redman included "St. Thomas" in his set-list two years ago, it was a declaration that he'd come to play. Taking on the master improvisor using his own signature piece showed guts. As recorded on Live at the Village Vanguard (Warner Bros. 45923-2), it was a showstopper. Redman took the song through unaccompanied cadenza after unaccompanied cadenza in a breakneck display of playful bravado that should bring you to your feet even when listening alone at home. Usually. With the Hales, it sounded flatter than I know the performance to be. The gross dynamics were there, as was information concerning pitch-phrasing, duration of notes, and vibrato; however, something vital in the extreme rhythmic complexity of Redman's improvisations upon the melody didn't communicate itself to me.

Do I have a theory about why swing was MIA with the Concept Five? Kinda. I suspect that the Five's tonal leanness, allied with some degree of dynamic compression in the bottom end, robs some music of vital, intangible rhythmic momentum. Much of swing is dependent upon extremely subtle distortions of the common pulse; blur those distinctions and you flatten rhythm. For what it's worth, that's what I think was going on.

So much speaker, so little time

In certain respects the Hales Concept Five is the equal of any speaker I've ever heard. Paul Hales's design brief—to build an affordable reference loudspeaker—is a worthy one, and you've got to respect what he has accomplished toward that goal. If you value that U-R-There sense that the performers exist between your loudspeakers, then the Fives are barking up your tree. They are uncolored and transparent throughout most of their frequency range. They have few peers when it comes to the presentation of the human voice—or voices. In all of those regards, I truly enjoyed auditioning these speakers.

Possibly because of the high standards they set in so many areas, I found their shortcomings extremely frustrating. They need to be played on the loud side of realistic loudness levels. Purists may find this a mark of their accuracy, but I found that sometimes I just wanted to turn them down—but at reduced levels, the Fives are unengaging. I missed a degree of low-end body that I know exists in live music, finding the speakers thin-sounding in their bottom octave and a half. And, to my ears, they flattened some of the subtle sonic cues that contribute to the sense of swing and that I, for one, could never live without.

I suspect that a truly excellent loudspeaker lurks within the ingredients of the Hales Concept Five. I wait for Paul Hales to bring it forth.

Footnote 1: Interestingly, after a day buried in Grove and Meyer and Cooper's The Rhythmic Structure of Music, the article that got closest to the point was Martin Colloms's "Pace, Rhythm, and Timing," published in the November 1992 Stereophile, Vol.15 No.11, pp.76–97.

- Log in or register to post comments