| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Hello - that format is damn near dead! Oh, thats right, its copy protected. That makes it worth doing.

"We're not in the business of screwing with people's memories or trying to annoy people," Gibson says with a nervous laugh that tells you he's read his name, perhaps in unflattering contexts, on the Web. He's aware that the recordings of such artists as Otto Klemperer, Sviatoslav Richter, and Jacqueline Du Pré are held sacred by many. While it may not be a matter of life and death, the passions are still fervent: screw up Herbert von Karajan's Wagner recordings and you'll face a swarm of Web wrath. Butcher Bruckner and the chat-room denizens will come a-creepin'.

"People are very fond and very protective, if you like, of their favorite recordings. That's a historical thing, really, isn't it? People grow up with something—it's the first record they bought or the first record they fell in love with—and they feel very sort of personally responsible for it. And you can understand that—I have particular favorite recordings as well. We're just re-presenting EMI's fabulous back catalog."

Of course, giving the core classical catalog its first high-resolution remastering job amounts to more than a mere re-presentation. In the first batch of ten Signature Collection SACD/CDs to be released in the US and Europe—a small percentage of the 100 released so far in Japan, the market this project was originally conceived for—a familiar recording like Du Pré's famed reading of Elgar's Cello Concerto for example, does sound appreciably more alive than in its long-available CD edition. By all accounts, Gibson and the Abbey Road crew have done a wonderful job on this series. The book-style packaging for each release, which includes a 40-page color insert of notes and photos, is similarly successful. Ten more hybrid SACDs in the Signature Collection, variously listing for between $22 and $27, depending on the outlet, will be released in November.

"It's a little bit like restoring a film frame by frame. Or cleaning an old master painting," Gibson says of remastering these recordings, some of which are over 60 years old. "You're trying to remove the layers of grime that have accumulated, and get back to the colors that the artist saw when he'd finished the painting in the studio. You're just trying to ease away some of the things that get in the way of hearing the music as the artists heard it when they recorded it."

As a Bruckner symphony that he's transferring to digital plays in the background, Gibson explains that, in contrast with the tape libraries and inventories of recording parts at most labels, EMI—which has wisely never allowed the Beatles' recording library to leave the secure confines of Abbey Road Studios—has been presciently meticulous over the years in the storage of the rest of its recorded archive. Housed in a purpose-built structure in West London, EMI's vault contains everything the label has ever recorded, from the earliest 78rpm records to the latest hard-disk drives.

"When we started this project for Japan, it was specifically for Furtwängler's recordings," Gibson says. "Now the period of recording for those was sort of 1940s–50s, so it straddled the end of the 78rpm era and the beginning of the analog tape era, so there were issues with sourcing the right original masters for some of those." He goes on to say that less than 10% of the Signature Collection is sourced from 78s. "Because these recordings have been worked on over the years, we are sort of familiar with the archives and what's there, and we were able to actually discover one or two tapes of Furtwängler that hadn't been used before, so we were able to use better sources for certain recordings: one of the Beethoven symphonies, I think, and the Brahms Violin Concerto, done live in Switzerland. That was a very early tape, from 1949, with Yehudi Menuhin.

"For the majority of the core catalog stuff that you see on Signature, these are all LP master tapes, well documented. Sometimes you will find that there is a question over the provenance of a particular, say, copy tape. So if it says it's a copy tape, then you say, 'Well, okay, so where's the original? Why isn't the original used?' That's when you need to do a bit of digging. When I say digging, basically we have files for each recording, which were put together at the time of the recording by the engineer and the producer and the editors. And they contain a variety of information, often useful information for us today, in terms of what EQ was used, when the LP was cut, and comments from the producer saying, 'I want this movement 2dB louder and this movement 4dB quieter.' So when the tape is played, [we can] take that into account."

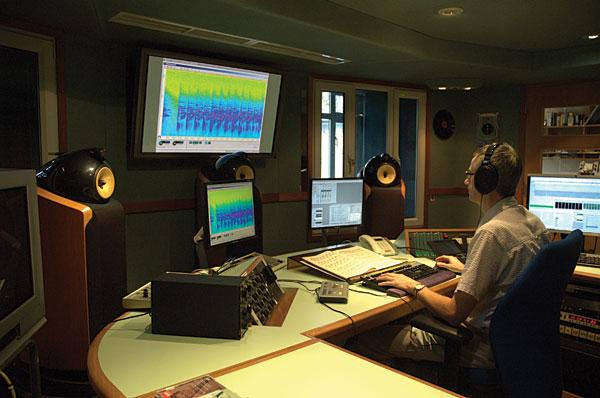

The shedding problems associated with aging, ¼" two-track tape are well known, and that's where the ears of Gibson and his fellow mastering engineers, Ian Jones and Andrew Walter, come in. Classically trained as an organist and pianist, Gibson has been a mastering engineer at Abbey Road since 1990, during which time he's worked on the 2009 remasterings of the Beatles' back catalog, the Beatles version of the video game Rock Band, and the Harry Potter soundtracks in 5.1-channel surround and two-channel stereo; he also mastered Alexandre Desplat's score for the film The King's Speech for CD release.

"You make the transfer [using the Prism ADA-8 Converter], you hear it while it's transferring onto digits, and then you work through it on our digital editing system here, line by line, with the score. We fix the things that need fixing, and where we can, we make a reference to previous CD versions, possibly the original LP release, and get a feel for the sound this recording has had in its previous incarnations.

"On an analog tape, you've got joins, you've got edits, the tape is cut and spliced together. Sometimes the analog edits, despite the best intentions and skills of the editors in the past, sound a little bit less than seamless. There's a bump or a jump, so we hear that [and] we can fiddle around digitally and make that join more seamless—get rid of any bumps and pops and clicks and things. Analog dropouts, where there's a little bit of gunk or something on the tape and there's a slight loss of high frequency—that's where you notice it, particularly in the ambience, and you hear a slight dropout in the left channel or the right channel or both channels—we can fix that by interpolation or using a software tool and make it seamless again, join it up. Some of the things we worry about, frankly, some people wouldn't even notice. But because it's going to be out on a hi-rez format, we took the trouble to remaster to the best possible standard. With all of these sorts of changes—improvements, if you like—the bottom line is, you don't affect the recording. If it affects the music, you don't do it, or you've got to find a compromise."

I've purchased about 10 SACDs from the new EMI re-release range, and I have found them extremely disappointing. Other companies such as Pentatone, Mercury and Sony Columbia have released older analog recordings to SACD ... simply doing a direct transfer from the master analog tapes direct to DSD ... and the results have been simply phenomenal, with warm, clean, beautiful analog sound, that is noticeably superior to the CD versions that preceded them. Even Universal / Deutsche Grammaphon have switched from using 24bit/96kHz to using direct analog to DSD for all their new re-releases (via Emil Berliner Studios) on SACD.

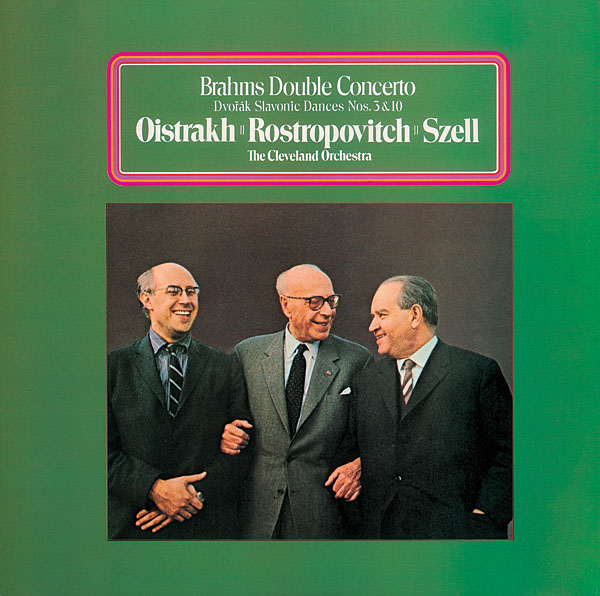

By contrast, the EMI discs I have tried sometimes have noticeably harsh distortion (e.g. the Brahms Double), have harsh digital sound, and peculiar sonics. Elgar's Sea Pictures with Dame Janet Baker sounds like it truly has had all the life sucked out of her ... I've never heard poor Dame Janet sound so utterly strangulated. Poor thing. The 1980s CD version is far superior, and that is a rather sad outcome, given the inherent advantages of SACD which have been wasted here.

Since other labels have success in their transfers, and EMI's results are in my view a fail, it would appear the blame lies entirely with the absurd process EMI use, described in the article. Instead of just going direct analog to DSD, they apparently do some convoluted set up with analog to 96/24, masses of processing, then back to analog, then to DSD. Bizarre. Defeats the whole purpose of using SACD/DSD.

I would agree that the presentation is excellent, though the booklets are difficult to extract the discs from, and likely to scratch them in the process. The only recordings I have been pleased with are the pre-1955 Schubert Dieskau releases, and I have no idea why these are successful, and the post-1955 releases are not.

To state the obvious, EMI needs to go shopping.

******

I loved reading the detailed synopsis of why the various remastering methods were chosen. Customers DO care, because it tells them about the things that matter to the content creators.

What's curious is that when someone takes an original tape master and cuts a new LP or does a direct digital transfer sans digitally editing, the customer praise is nearly universally positive. EMI and others seem to have this vast wish list of perfecting things that they can't deny themselves of, with variable results ensuing. And then wonder why customers question them. Really?

Just think of all the time it took to create new masters. Golly, they must have been in terrible shape.

Mr. Gibson wants to say that simply threading the tape and doing a straight transfer would have resulted in lower overall quality, but of course that won't be proven here. The further notion that customers don't know what they're talking about is unfortunate. How can there be such a chasm between what we hear and what they hear?

Listening aside, I'm comfortable questioning the veracity of taking an analog format and transcoding it several times, something I hope Abbey Road would normally agree with.

Tape to SACD is like taking a homeless person who has not showered in about 10 years and putting them in a new Armani suit.

These recordings are not highres even if they are on SACD, or sampled to 24/96 flac for download.. Nice container (the Armani suit) but the BUM still stinks (Tape)

Mark Waldrep

http://twit.tv/show/home-theater-geeks/126

I'm afraid your reference links don't convince.

Mr. Waldrep makes very fine recordings but he unfortunately succombs to passing judgment on what good sound is by labeling various technologies as either "HD" or not "HD." He talks little about sound and more so about technical benchmarks and that's worrisome. I nevertheles of course respect his years of experience and results.

At best, "HD" (he uses that label frequently) is a marketing designator, like all acronyms a descriptive shorthand for various levels of technical acheivement digital accomplishes.

The underlying assumption is that something "HD" reaches higher than the norm, higher than the average, and oh my yes, professional analog has done that for many decades!

If anything, kevon27, you both actually have it backwards. I suggest listening more and kvetching about "analog's limitations" a little less.

Also, the marketer in me finds the cd covers for the reissues a missed opportunity. Others have done a much better job packaging reissues. I always like to see the original album convers transferred to full CD jackets. That's just me though, others might not care.

Nick

One of my customers pinged me this morning asking about this article and whether it's "snake oil". I read the article and then the comments...I'm surprised to see a couple of links to my site and a piece that Scott Wilkinson did a a while back.

Thanks kevon27 for bringing up the very real issues surrounding the whole remarketing of old, decidedly standard definition (if 50 dB of dynamic range does it for you deckeda...then fine) on any format...let alone going to DSD, which I regard as capable of doing CD resolution very well, but has very serious limitations. DSD was abandoned by Sony in 2007 for good reason.

My whole point is that "HD" should NOT be a "marketing designator", it should actually be associated with a certain level of quality as much as Ultra HD Video is. It should not be appropriated by anyone wanting to market old as new again. For example, what is HD-Radio (64-96 kbps...a good mp3 files is 128-256!), what is HD Windex, HD Skin, HD sunglasses...it goes on and on.

As I have written repeatedly (I do so daily at RealHD-Audio (dot) com), like what you like. It is the ultimate experience that matters most...including vinyl and analog tape. If analog tape works for you and you want to purchase $500 albums, then nobody can argue with you.

But "HD" is not a relative improvement, it means fidelity that eclipses the potential of those formats (CDs, vinyl LPs, analog tape) in terms of dynamics and frequency response and other important specfications. I have placed 12 examples (of various genres) of real HD-Audio that you can download and compare to analog tape at RealHD-Audio. If you don't ever heard real HD-Audio, you can't talk about it.

As for EMI's choice to issue SA-CDs of their catalog...it's wrong headed in so many ways. If they really want to take advantage of audiophile's seeking "perfect" physical versions of their catalog (because of the irreplaceable performances), they should follow Universals lead and adopt "High Fidelity Pure Audio Blu-ray" as their delivery format.

I may be a late SACD adopter, and late catching up to these EMI reissues, but I just got my first: Carl Schuricht'a Bruckner 8 & 9 and it is fantastic - great performance, great sound, great packaging, great price at $19.99 - what's not to love? I'm hooked, I want more