| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Klaus Heymann: A 20th-Anniversary Chat with the Founder of Naxos

When Hong Kong–based music lover and electronics-equipment distributor Klaus Heymann (footnote 1), now 70, first began organizing classical-music concerts as a way to boost sales, he had no idea he would end up founding the world's leading classical-music label. But after starting a record-label import business and meeting his future wife, leading violinist Takako Nishizaki, the German-born entrepreneur sought a way to promote her artistry. First he founded the HK label, which specialized in Chinese symphonic music (including Nishizaki's recording of Butterfly Lovers, the famous violin concerto by Chen Gang). Next he established Marco Polo, a label devoted to symphonic rarities.

Footnote 1: Stereophile last published an interview with Mr. Heymann in February 2000.—Ed.

By 1986, when his Pacific Music had become the biggest international classical distributor in Southeast Asia, Heymann envisioned a budget-priced CD label that would offer his Southeast Asian customers classical CDs at the same price as LPs. Naming the new label Naxos, after the Greek island long associated with art and culture, he released the first five of an anticipated 50 titles. Then, on discovering that the major labels had virtually no interest in entering the bargain market, Heymann seized one opportunity after another to expand his vision.

In an interview last summer, as Naxos celebrated its 20th anniversary, Heymann told Newsday International that his label is now in the position to survive and thrive without selling CDs. Wondering if Naxos was planning to stop selling CDs, I contacted the label's former US publicist, Mark A. Berry, to arrange a chat. A week later, Heymann and I spoke via Skype (footnote 2).

Jason Victor Serinus: In Alexandra Seno's Newsday International article of July 30, 2007 [], you're quoted as saying, "We could live very comfortably if from tomorrow we never sold another CD."

Klaus Heymann: What I was trying to say is that our revenue from other sources is now big enough to let us not only survive but lead a healthy, profitable existence. Of course, we don't want to lose the physical sales, which are still the daily bread and butter. But if it all went away, and we had to live solely on download revenue from our streaming library, licensing, ring tones, and all the other stuff, we'd still be extremely profitable—maybe more profitable than we are now.

JVS: Maybe more profitable? Are you losing money on CDs?

KH: Basically, on most new recordings, especially with orchestral material that's in copyright, we nowadays don't recoup our investment. We record to broaden our catalog and make more stuff available.

JVS: Your catalog of over 2500 titles is amazingly rich. Sometimes it seems as though you intend to record every piece of classical and new music ever written. Do you record some pieces simply so they can be recorded and available to libraries, and as an act of love and dedication? I would think that some of these titles can't possibly make you money.

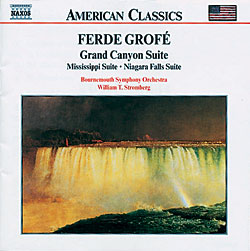

KH: [Laughs] The repertoire policy is quite diverse. There are many factors we consider when we make a recording. Number one is, we want to have a well-rounded catalog of all really important standard repertoire. You will not believe it, but there are still gaps in our catalog. We don't have all the Haydn masses, for example, so they are being recorded over the next three years. We don't have all the Mozart masses. We don't have the Haydn piano trios. We just finished all the Monteverdi madrigals, and are now starting on the Gesualdo madrigals. There are chunks of repertoire that we haven't yet recorded that are essential for any company that claims, as we do, to be a complete classical label. Second, we have a lot of big series underway: Schubert songs, Schumann songs, Liszt piano music, Scarlatti piano sonatas .†.†. all these have to be continued at a reasonable pace. Third, we have all the national series that are going on: Spanish Classics, Japanese Classics, American Classics, and so on. Those series have to be fed.

Then we have a very substantial business of licensing music to educational book publishers. To feed that market, very often we have to look at what's still missing in the history of classical music. If you buy Grout and Palisca's A History of Western Music [Norton], it comes with CDs whose music is supplied by us. The music may not all come from Naxos—we license from other labels—but basically the music that comes with music-appreciation books and music-history books nowadays is normally supplied by Naxos. Someone at Naxos is now going through Grout's history and marking down every work he makes note of, because we plan to record every work mentioned in the book. Whether the title sells or not is really not essential, because we make money from licensing and other applications.

Then we need music for the Naxos Music Library. It's an essential resource. I meet people who can't imagine life without it. You have access to 20,000 recordings at the click of the mouse, complete with playing times, music notes, and, soon to be added, instrumentation. Whether you like the sound quality or not is another issue (footnote 3). So we record works for the library. Before doing so, we also look at what the other labels have recorded that is needed for the service. We may decide not to record something because we already have access to it for the library and licensing.

Then we need music for the Naxos Music Library. It's an essential resource. I meet people who can't imagine life without it. You have access to 20,000 recordings at the click of the mouse, complete with playing times, music notes, and, soon to be added, instrumentation. Whether you like the sound quality or not is another issue (footnote 3). So we record works for the library. Before doing so, we also look at what the other labels have recorded that is needed for the service. We may decide not to record something because we already have access to it for the library and licensing.

Other projects are brought to us by artists or orchestras who want to record certain things. We accept several but not all of them. Then we have to keep our house artists busy. We have people with whom we have a long-term relationship. These include Marin Alsop, JoAnn Falletta, Ilya Kahler the violinist, and quite a few others. They often have ideas of what they'd like to do, some of which we accept. We have to keep them happy.

Then there are relationships with festivals. We do all the productions for the Rossini Festival in Germany, which means we'll eventually have all the Rossini operas in our catalog.

In other words, there are a great variety of reasons why we record a work.

Footnote 1: Stereophile last published an interview with Mr. Heymann in February 2000.—Ed.

Footnote 2: When Heymann called my landline using Skype, he mildly berated me for not taking advantage of Skype's free computer-based phone service. While offering lame apologies, I decided not to tell him that I don't even own an iPod.

Footnote 3: NaxosMusicLibrary.com claims, "The standard streaming rate of 64kbps produces near-CD quality. If you have a broadband Internet connection, you can choose 128kbps for a quality equivalent to CD. If you have a dial-up Internet connection, the music is streamed at 20kbps, which is equivalent to FM sound quality." This is untrue. While 128kbps is standard for Internet downloads, it is relatively easy to hear the difference from CD quality (1100kbps on MusicGiants). In John Atkinson's opinion when I discussed this interview with him, "192kbps is better but not much so. You need 256–320kbps to get sound quality that will fool some of the listeners some of the time that they are listening to CD." As for 20kbps being FM quality, "Only if you have a piece of wet string for an antenna and live in a multipath forest."

- Log in or register to post comments