| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Music in the Round #24

Good things come in threes, they say. Well, three-channel power amps suit me just fine. My main component rack is at the back of the room, so I split power duties between a two-channel amp under the rack to drive my rear-channel B&W 804S speakers and, way at the front, either three monoblocks or a three-channel amp for the front three B&W 802Ds. I do this to ensure that the timbre of the front three channels is consistent. The outstanding performance of the Simaudio Moon W-8 dual-mono power amp (Stereophile, March 2006) almost tempted me to go with a stereo amp and a monoblock, but voicing and balancing a multichannel system with equanimity makes me want as much simplicity as possible. I guess manufacturers and users see it the same way; many new three-channel amps are coming on the market.

Footnote 1: "Monaural" literally means "single-eared," which may be fine for listening, but we prefer "monophonic" when referring to single-channel products.—Ed.

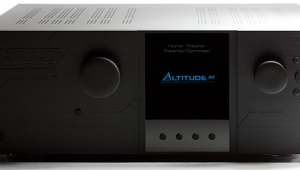

I first saw the Mark Levinson No.433 at the 2006 CEDIA Expo, and immediately asked about getting one for review—I'd never had a Levinson amp in my system, and this one seemed perfect for my setup. It looked relatively sleek and compact for its impressive specs, and besides, I just wanted it. (All specs are listed here.)

ML calls the No.433 a "triple monaural" amp because each channel is supported by its own power supply consisting of a 684VA transformer and 48,000µF of filtering and storage (footnote 1). Each channel has balanced and unbalanced inputs, is fully balanced through all the voltage-amplification stages, and is built on its own Arlon PC board, which is supported and connected to its individual power supply by bus bars of oxygen-free copper. Fault sensing includes detection of DC on the output, excessive output current flow, over- or undervoltage at the AC input, and unsafe temperatures anywhere in the amp. In addition, ML says that there's a controlled clipping circuit that both prevents the output devices from saturating and, by a wave-shaping action, eliminates HF harmonics that would be generated by clipping. Real-world bottom line: The No.433 costs $10,000, puts out 200Wpc into 8 ohms or 400Wpc into 4 ohms, and weighs 122 lbs (55.5kg).

So it was with great effort that I single-handedly maneuvered the No.433 into place between my front left and center 802Ds. The handles on the rear panel were a big help, and transferring the cables from the Bel Canto REF1000 monoblocks was a snap. I used the No.433's XLR inputs, so it was necessary to first remove the pin 1–3 shorting straps and save them for future use of the amp's RCA inputs. The No.433's output terminals have big-eared plastic nuts that let me clamp down the spade lugs firmly but easily. Of course, the nuts are plastic only on the outside; gold-plated, high-current, custom-made parts make the electrical connections. Also on the rear panel are a Power/Save mode switch, two 1/8" remote trigger jacks, an RS-232 port, two Link2 communications ports, and a switched IEC AC input.

On the front panel, below the Mark Levinson logo, is an LED that indicates the amp's operational status: Off = AC off; Dim = Sleep with power supply off, only supervisory circuit active; Slow Blink = Standby with power supply on, voltage gain stages powered, output stage off; On = On with everything fully operational. In Sleep mode, the supervisory circuit draws less than 15W, compared with draws of 75W in Standby and 375W in On—even with no signal. To lessen my contribution to global warming, I kept the amp in Standby most of the time it was not being used, even though it had formerly been my habit to leave all my amps on all the time. If I was going to be away for the weekend, I let it Sleep.

Below the LED is the Standby button and the AC Power switch. Operation begins with pushing the Power button once, then Standby once, to shift the No.433 from Sleep to Standby. After a two-second delay, the Standby switch toggles the amp between Standby and On. Press and hold it and the amp goes to Sleep. It worked just that way, and although the LED will also indicate various fault conditions, I failed to evoke any. Nor did the No.433 produce excessive heat or any fan noise—it has no fan. Despite its size, power, and appetite for current, the No.433 is a fully domesticated device.

I used the No.433 briefly with Pioneer S-1EX speakers that I reviewed in March, but it spent—still spends—most of its time running the B&Ws, which it did superbly. At first I heard little difference between the No.433 and the other amps on hand, and that was as it should be. Products as refined and demanding as these shouldn't offer widely divergent tonal or dynamic presentations. But as I listened to a widening range of music, the particularities of the Levinson became apparent.

First, the No.433's dynamics and transient response were beyond reproach. Although rated at only (!) 200Wpc, the Levinson was easily as potent, subjectively, as any amp that has passed through this system. Chalk this up to its sophisticated balanced circuitry, its individual power supplies for each channel, or whatever else contributes to its 122 lbs, but the supposedly power-hungry 802Ds never asked for second helpings. The soundstage was as wide as I've ever heard with these speakers, and satisfyingly deep.

The No.433's midrange clarity was its forte, and served recorded voices very well. From baritone to soprano (I'll deal with the basses next), the Levinson allowed both the B&W 802Ds and Pioneer S-1EXs to seem just a bit more revealing and empathetic than before. It wasn't so much a highlighting or midrange emphasis as a complete lack of grain or confusion. Next, I noticed that I could consistently discern, at relatively low SPLs, details in the bass that I had heretofore heard only at much higher volume levels. Again, this was not due to any bass emphasis, or to changes in speaker position or acoustics, but to the No.433's ability to give shape to sounds that could otherwise be obscured by what was going on in the midrange and treble. One result of this was that the low end of deep voices that descend to the frequencies where room modes begin to have their pernicious effect were not differently colored from the upper end of their range. The very lowest bass was equally tight and potent.

It was in the high frequencies that the No.433 most distinguished itself from the other amps on hand. The clarity of its midrange seemed to carry on up through the highest frequencies without restriction or loss of resolution. With the 802Ds, the result was extremely satisfying—the No.433 opened up the soundstage while taking nothing from the defining qualities of the bass and mids. I doubt I would have made such a determination with earlier 800-series speakers from B&W, but the smoothness of the 802D's diamond tweeter, particularly as it approaches the crossover frequency (4kHz), combined with the No.433 in a way that was a revelation.

That revelation occurred when I put on Christoph Eschenbach and the Philadelphia Orchestra's new SACD of Saint-Saëns' Symphony 3 (see sidebar, "Recordings in the Round"). From the very soft beginning, I could hear individual instrumentalists and "see" exactly where each was seated. As the forces gathered, there was no loss of such specificity or balance, even in tuttis. Add the organ-pedal tones in the second movement and, again, there was an expansion of the tonal and dynamic palettes, but with no compromise of the rich detail. I was transported.

The No.433 might seem a bit bright in direct comparisons with other amps, but, as I've emphasized before, you can't make a completely objective determination of a product's accuracy with only subjective tools and no primary references. With the Pioneer S-1EX speakers as well, the No.433 created an impression of transparency and lightness, but it was as if the otherwise excellent mids and lows played less of a role in defining the sound's character. Perhaps this was due to the difference between the B&Ws and the Pioneers' more highly damped bass tuning. The Bel Canto REF1000 monoblocks, despite their power, had a bit less slam than did the No.433 with either speaker, but they provided a remarkably satisfying spectral balance with the Pioneers, much as the Levinson and the Classé CA3200 did with the 802Ds. I continue to waffle about whether I preferred the Levinson or the Classé with the B&Ws. The Levinson made them sound tighter and quicker, while the Classé made them sound a bit more warm and rich. Given my experience and my current room acoustics, I'd go for the Levinson No.433, but the difference in price is substantial: $10,000 for the Mark Levinson No.433 vs $6000 for the Classé CA3200. I can think of a lot of other ways to spend $4000.

Back to Bassics—JL Audio's f113 Subwoofer

The arrival of Christoph Eschenbach and the Philadelphia Orchestra's spectacular new SACD of Saint-Saëns' Symphony 3 drives me to say a bit more about JL Audio's Fathom f113 subwoofer (see "Music in the Round," November 2006). Because I listen to music, not movies, in my main system, the f113 is not called to duty every day. If fact, most of my listening is in two-channel stereo, for which there's no easy way to do optimum bass management in this all-analog system. But after my first listen to this disc, I got myself off the couch—I had to hear it with the sub.

The disc is 5.0-channel, so I tried two ways: 1) I hooked up the f113 in parallel with the L/R channels and used the built-in LP filter to roll it in from 40Hz down. Then, 2) I used the Bel Canto PL-1A's bass management to set all of my speakers to Small. The latter might seem suboptimal (sorry) because the crossover to the sub is fixed for all channels at 80Hz, and a lower crossover frequency is more effective with the B&W 802Ds. Nonetheless, I greatly preferred that configuration; in this room, the f113 is a vastly superior reproducer of low bass than even the quintet of B&W floorstanders.

The disc is 5.0-channel, so I tried two ways: 1) I hooked up the f113 in parallel with the L/R channels and used the built-in LP filter to roll it in from 40Hz down. Then, 2) I used the Bel Canto PL-1A's bass management to set all of my speakers to Small. The latter might seem suboptimal (sorry) because the crossover to the sub is fixed for all channels at 80Hz, and a lower crossover frequency is more effective with the B&W 802Ds. Nonetheless, I greatly preferred that configuration; in this room, the f113 is a vastly superior reproducer of low bass than even the quintet of B&W floorstanders.

In 5.0 channels, the Saint-Saëns was no less than glorious (see above), and the organ was powerful, rich, and distinctive in its colorations. In fact, it was simply the best-sounding recording of this piece that I had heard. But, like Oliver Twist, I wanted more, please, sir. With the f113 rolling in below 40Hz, there was added authority and weight in some, though not all, of the organ-pedal passages. It was thrilling, but not all that different from the unaugmented 5.0 sound.

With the invocation of bass management, with which I passed the low end over to the f113 below 80Hz, there seemed to be a dramatic expansion of the entire soundstage and an increased definition of the extreme bass, to go along with the enhancements noted above. At several points in the second movement I could barely hear the organ, but I could feel it through my feet—and this in a steel-reinforced concrete building. Who knows what others in the building might have thought was going on?

Why was this so? I think there are two reasons. First, the f113 is simply capable of more output with less distortion below 40Hz. Second, the f113 is equalized to be more linear in this region. I didn't measure the B&W 802Ds, but if the unequalized f113 showed a highly irregular response in this room, odds are that the 802Ds, positioned as they were for maximal imaging and midrange smoothness, probably had a low-end response that looked like a view of the Alps. Bass management simply deleted this and passed along those frequencies to the equalized and powerful f113. The result? My entire system, good as it was, has been pushed another step forward by yet another example of complementary advances in software and hardware. Now I need to rethink all of my connections to permit better and more frequent use of the JL Audio Fathom f113...

Next Time in the Round

Having distributed my Stereophile card to many prospects at the 2007 Consumer Electronics Show, I hope lots of juicy stuff will soon arrive. The Audio Research MP-1 and the Cary Audio Cinema 11 pre-pros are next in the queue, along with some more discussion of equalization. As for recordings, the spate of multichannel SACDs continues. See you in July.

Footnote 1: "Monaural" literally means "single-eared," which may be fine for listening, but we prefer "monophonic" when referring to single-channel products.—Ed.

- Log in or register to post comments