| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

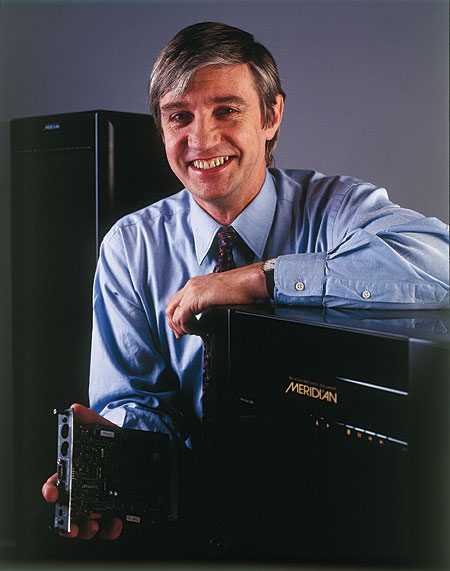

Bob Stuart: The Prime Meridian

There are many colorful characters, many high-profile movers and shakers, in high-end audio, but there are only a few whose influence extends far beyond the promotion of their own brands. One of this exalted and mighty handful is Robert Stuart, chairman and technical director of the UK's Meridian Audio.

Softspoken, with a disarming smile and a puckish sense of humor, Bob Stuart has been at the helm of Meridian ever since he and the outstanding industrial designer Allen Boothroyd cofounded the company as Boothroyd-Stuart in 1977, and in the last 15 years has quietly taken on a much larger role in the industry. In 1994, with DVD-Video on the horizon, Stuart chaired a pressure group, the Acoustic Renaissance for Audio (ARA), which aimed to make sure that the film industry and the electronics companies didn't forget about audio quality in their rush to offer a new video format. These efforts were rewarded by the inclusion of the two-channel, high-resolution, 24-bit/96kHz audio option in the DVD-Video standard, which made possible the DVD-Audio disc.

Meridian was the only UK company to become a member of the DVD Forum, the body that determined the DVD specification. In what he calls "the lossless summer" of 1998, Stuart and his team showed the DVD Forum how Meridian Lossless Packing could make multichannel 24/96 audio possible, and MLP was adopted as part of the DVD-Audio standard. And after this, Stuart became deeply involved in the process of formulating the requirements for a new high-resolution video carrier.

Meanwhile, back home in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, the expanding Meridian had already outgrown its new factory, which had been ceremonially opened by then-Prime Minister John Major in 1996. In 2004, the company acquired its present, very large and impressive, headquarters and factory building, which had been built for the short-lived TAG McLaren Audio operation. Scaled to TMA's grand ambitions rather than to its actual needs, this superb modern facility came complete with anechoic chamber, EMC test suite, and several purpose-built listening/screening rooms with full acoustic treatments—although, as Stuart says, "We did tweak all the rooms. We certainly made it sound like we wanted it to!"

When I spent an afternoon there with Bob Stuart some months ago, he talked of Meridian's recent life-changing deal with Faroudja, new formats, and the future. But the first topic to come up was the state of the CD-player market.

Bob Stuart: It's certainly alive and well where we are, Steve. The new audio formats haven't produced a catalog of any size. If you are a music lover, you have no choice but to listen to CD, or to download it in some awful format.

When DVD came along, we could and we did make DVD players that played back CD very well indeed—but a dedicated CD player is always better than one that does other things, no matter how hard you try. There are also people who want a CD player because they actually don't want video—the customers who say, "I don't want a DVD player in my house, I just want to listen to music."

Now, the Meridian 800 DVD machine is a fabulous DVD player, but it's also a really good CD player. But nevertheless, when I took out the DVD functions, when I took out the ability for it to make a picture, the sound quality on CD got better. It's all about refining and refining. No matter how well you design something, if you can remove a potential source of interference, it'll get better.

That's how we did the 808. It's the most musical machine—you put a CD on it, you just get lost in the music. Because it has no glare, it is tremendously open—deep, tremendous space—it's really, really easy to listen to. And that's the kind of sound that Meridian has always headed for. Absolutely locked: the sound of real instruments in real space.

Steve Harris: So 16-bit is enough, then?

Stuart: No. It's not enough. On some recordings you can hear the limitations of that. More the limitations of the 44.1kHz than of the 16 bits. Sixteen bits give you a 90dB dynamic range. If the recording is properly made and the A/D converter's good, and at the mixing or mastering stage they didn't forget to dither it properly, within the window between the peak level of the music and the noise floor of the recording venue, then the hiss of correctly done 16-bit audio is around the room-noise level—sometimes it's above it, and that's a problem. But 44.1kHz, there's no doubt that that was a bit mean at the top end, and on certain instruments, violins and so on, you can hear that—just a little edge sometimes, which comes from that sample rate.

We make it a lot better in our player because we say, "Well, okay, there's nothing we can do about the way the recording was made, but we don't have to compound the error by using more and more and more filters at this speed." So in the 808 we upsample in resolution terms so the player is in fact playing back at 176kHz/24-bit. And that gives a much smoother sound than playing back at 44.1kHz. If the recording's well done, it's okay.

More bits would be helpful. Back in the late 1980s, we did a lot of work on noiseshapers. And we made A/D converters that could be used for making CDs—a lot of the Stereophile discs, for example, used the Meridian 518 or 618 noiseshaping processors, and a lot of recordings from people like Tony Faulkner—they'd start with 20-bit and then use our processor. So you can get more than 16 bits' effective dynamic range on a disc. But to play that back, you have to have a player that doesn't do stupid things, and 99.999% of players will truncate a signal. Our players won't. So if you've got a beautifully made recording, you can actually get more than 16-bit anyway. But you can't get more than 44.1kHz.

The recordings with the 518—listen to some of the ones that John Atkinson did, or Tony, they're breathtakingly clear. It's a question of how close the microphone is, how important the 44.1kHz is. For a lot of natural acoustics, chamber music, things like that, it's less of an issue. But if you're right in close—like that thing we were listening to here this morning, where the microphone is clearly stuffed into the bell of the saxophone—switch to 96kHz recording and it's better.

But we believe that we should provide the best instrument for people to enjoy a music collection. People say, well, "This is better," or "SACD can do this," or "DVD-Audio can do that"—but if you can't find a recording by the artist you want of the piece you want, it's a nonstarter.

Harris: Even if CD sales are healthy, Meridian's primary focus today is the home theater market. In mid-2005, Meridian signed an exclusive worldwide agreement to manufacture and distribute one of the most respected and innovative video-technology brands.

Stuart: When we were approached by Faroudja, we'd worked with them over a number of years at shows. They'd put up an exhibition and we'd give them a sound system, and we'd use their projector in our booth, stuff like that, so we kind of knew each other. And they just said that what they were looking for was the company that matched their brand in audio, the company that did the best quality, that could market the product.

- Log in or register to post comments