| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

John Doe is great.

My wife's favorite album is "A Year in the Wilderness."

Few people make albums about isolation and loneliness sound as appealing as John Doe does. That's what Doe has achieved with his latest solo release, Fables in a Foreign Land (LP, Fat Possum FP 18001). Set as a song cycle in the 1890s, the album's 13 songs reflect Doe's penchant for dust-and-diesel storytelling, within an acoustic-trio format. It's "telling stories and playing music around the modern campfire," Doe said in an interview.

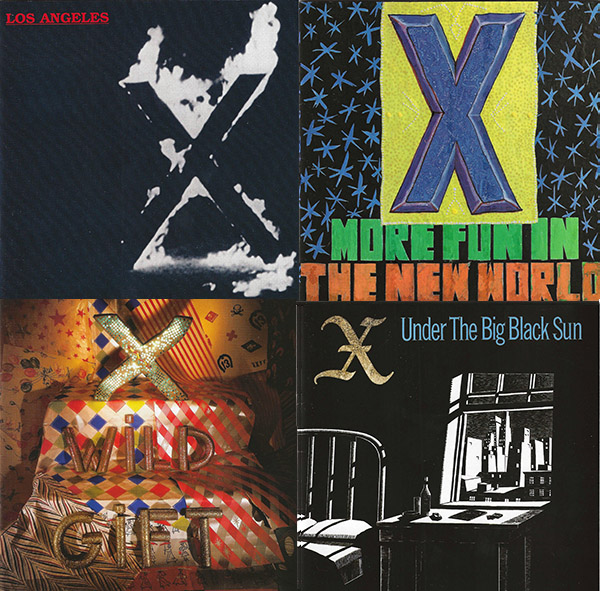

Doe's mining of what some call the "dark folk" vein during the latter portion of his solo career hearkens back to his roots in X, the Los Angeles–bred iconoclast punk band he co-founded in 1977. Though X could be raw and confrontational, the band had killer vocal harmonies and a rockabilly-tinged sonic edge. X caught the eye and ear of Ray Manzarek, cofounding keyboardist of the Doors and long-established LA rock royalty, who produced the band's first four albums (footnote 1), providing some recording lessons in the process.

"What Ray brought to us was validation," Doe reflected, as we chatted before our recent interview. "He was a bona fide rock star with one of the coolest bands I thought ever was, especially as a teenager. He also taught us what's most important in a recording: a good performance! If you don't have a good performance, even if you add all kinds of bells and whistles, it's still gonna sound bad. It's not gonna sound convincing, because you're really just making a record of what you did in the moment."

What Doe has been doing for nearly six decades of recording has been, in essence, to extrapolate the title of a 1986 documentary about the band: to take unheard music and make it be heard. When I suggested that, Doe answered, "I'll take that compliment, but that title was probably inspired by T. S. Eliot."

Doe is correct: The title of that documentary, The Unheard Music (footnote 2), comes from Eliot's Four Quartets (footnote 3). A passage from "The Dry Salvages," part of Quartet No.3, ends with "music heard so deeply / That it is not heard at all, but you are the music / While the music lasts." Under his own name and under the rubric of the still-vibrant X, Doe is making music to last a lifetime at least. In our interview, Doe explained his use, in Fables, of an acoustic-trio format, the relationship between vocalists and microphones, and a change to the wording in the X classic "Los Angeles." The interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Mike Mettler: Tell me how you work with your label, Fat Possum, to get what you want on vinyl.

John Doe: Oh, let's see. They do a specific master for vinyl, which is critical. They also have a good history with both Steve Berlin and Dave Way (footnote 4). I trusted them, and it turned out great. When I got the reference disc, it was good to go.

Fat Possum built their business plan on R. L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough—that's my kind of company (footnote 5). Can you imagine saying, "Here's my business plan. I'm gonna base it on two guys who are in their 50s and 60s that nobody knows—but they're amazing"? [Laughs] It's like, "Yeah, that's cool." It just means you're going with your heart and your intuition, not some logical, thought-up, premeditated nonsense.

Mettler: I read that you and your fellow members in the John Doe Folk Trio recorded Fables in a Foreign Land live in the studio in Austin, Texas, with all of you in the same room working face to face. Is that correct?

Doe: Yes. It was all done at Public Hi-Fi, the studio built and run by Jim Eno, the drummer from Spoon. It was COVID time, nobody was touring, and we had a year and a half to figure out how we wanted it to sound.

When it came time to record, I asked Steve Berlin of Los Lobos if he would be part of it, and he said yes. Then I asked my friend Dave Way, whom I've worked with many, many times, and he said yes, too.

We all set up in there: Me [vocals and acoustic guitar], Kevin Smith [upright and electric bass], and Conrad Choucroun [drums and percussion], all looking at each other. There were no headphones. There were just a bunch of mikes and a ton of bleeds, so we had to play. And we had to play really, really good.

God bless all those classic rock records, but thank goodness we're many years away from Steely Dan. There's just not a hair out of place on those records. You wind up thinking, "What the hell? Where's the juice? Where's the messiness?" So, it was pretty rewarding to just record and know that this is the way it's gonna be.

Mettler: I see your working with Fat Possum as a seal of approval from an artist who's been on major labels in the past but can now feel more invested in—not as a numbers act or a sales generator, but as a real, creative person.

Doe: Yeah, well, I haven't had that double-edged-sword label choice to make in some time, and God, am I relieved.

Mettler: Fat Possum also brought the first four X albums under their wing, in 2019, for reissue.

Doe: Yes. We got back all those masters for the first four records, and in April 2020, they also put out the newest X record, Alphabetland, because—well, because we could! We had finished it, and we were thinking about putting it out in September, but they said, "Screw it! Let's just put it out now. We've got a captive audience. Everyone's at home. Everyone's wishing they had something to do." I thought that was really cool of them.

Mettler: When you're listening to a mix with your producer and engineer, do you have a picture in mind of what needs to be captured?

Doe: I rely on Dave Way to know that. We tried a bunch of different things, and then I said, "Yeah, that's the one," and we went with that.

Mettler: Can you give me a sense of the proximity of the three of you in that room? How far apart were you? How was the album recorded?

Doe: Oh, it was maybe 10 to 12 feet. We did put up one baffle, between Conrad's drums and me. The one thing we did do is, we'd record it on tape, dump it down to Pro Tools, and then we would cut between takes. Like, if there was a one- or two-measure section where there was a bum note, we'd cut it. I've been told they did that on jazz records like those done by Rudy Van Gelder. Conrad has great time, so all the takes were about the same speed, and we could do that kind of editing with the sound.

Mettler: I've watched the video clips you shot for three of the songs on Fables; they are in black and white. There are some color sequences in "El Romance-O," but you are living in black and white there.

Doe: That's true. I'm super-grateful that Gilbert Trejo, who's done a bunch of other videos, was willing to work on that. We just loosely talked about having some sort of a story between a mentor and an apprentice, where the apprentice becomes the mentor and the mentor just sort of fades away. That's what happens to people who are unreliable. Liars. That's what mentiroso means in Spanish: a liar.

Mettler: In the "Never Coming Back" video, you're standing in front of a cool-looking microphone. Was it just used in the video, or was it used during the recording sessions?

Doe: I didn't use that one in the recording, but I use it live. It's from a new company called Ear Trumpet Labs. They make microphones designed for bluegrass groups and more acoustic settings, but you can get right up on it, and it works. It's got a big diaphragm, so it's got a little bit more oomph. I've used it live several times, and it's a really great mike.

Mettler: In the video, it appears halfway down your chest when you're standing in front of it. Maybe it was positioned that way for the visual framing. When you're actually singing into a mike, are you "right up on it"?

Doe: Oh, it totally depends on the mike. With recording mikes, you have to be a good 6" away from them. But with most traditional live mikes, you're right up on them and touching the windscreen.

Mettler: Johnny Mathis once told me he had a specific distance for any microphone in any studio. He wouldn't do it any other way.

Doe: Ah, and just think of what he was going for, with that most magical voice—ever! Anyway, that was a big factor in our choice of going with Public Hi-Fi as the studio. They're very technical, but they still have that "raw" sound and great mikes and outboard gear. I leave it to the professionals, but I still know the difference.

Footnote 2: The 1986 documentary was directed by W. T. Morgan.

Footnote 3: T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets was published individually between 1936 and 1942, and subsequently made available in book form in 1943.

Footnote 4: Berlin, Way, and Doe are the album's co-producers; Way also recorded and mixed it.

Footnote 5: Fat Possum Records was founded in 1991. Blues artists R. L. Burnside (1926–2005) and Junior Kimbrough (1930–1998) were among the label's most prominent early signings.

John Doe is great.

My wife's favorite album is "A Year in the Wilderness."

Really worth people's time!