| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Luxman M-800A power amplifier Page 2

But even from a cold start, the Luxman M-800A made music with extra doses of smoothness and unforced ease that the MF kWs lack. And, like the MF kW750, the Luxman seemed to have no difficulty whatsoever driving my Wilson MAXX 2s. Not for a moment during the many months the Luxman was in my system did I sense that it was coming close to clipping or sounding strained—this from an amplifier that outputs only 120Wpc into 4 ohms, compared to the kW750's 1100Wpc.

Nor did the M800-A have any trouble maintaining a firm grip on the MAXX 2s' bass bins. The bottom end was a bit warmer and lusher than my reference kWs, but not at all soft, loose, or sluggish. Kick drums and electric bass had appropriate attack, body, and impact, while acoustic bass sounded full-bodied, woody, and nicely balanced between the attacks of the player's fingers on the strings and the response of the instrument's large, hollow body. The lower register of the acoustic piano was draped in a fine layer of transparent velvet that didn't soften or mute the hammers' attacks.

The M-800A had enough low-frequency extension and drive to reproduce the spaciousness and full weight of the performing spaces of live recordings made in large and small venues, while never submerging lower-register instruments in the soup—something that warmish-sounding amplifiers can sometimes do.

The Bill Evans Trio's Waltz for Debby produced the sensation of the Village Vanguard's space and its deep corner stage with a solid, holographic image of the trio dramatically emerging from a backdrop of aural black velvet (45rpm LPs, Analogue Productions, out of print). Handclaps sounded appropriately fleshy and not at all soggy, and while Paul Motian's shimmering, dazzling cymbal work was somewhat less brash and metallic than through the kWs, it didn't sound softened or muted, and had a sweet, chimey ring.

The Luxman's sound was definitely on the warm, velvety side of the great sonic divide, but this has been achieved without sacrificing immediacy, transparency, or transient clarity—and, most important for the listener, without inducing boredom or lack of interest. A warm sound can do that. Warmth can induce comfort, but too much warmth can make you want to open the sonic window and let in a cold, refreshing slap in the face.

But warm isn't necessarily the same as smooth. Cool-sounding amplifiers (and cables, for that matter) can also sound too smooth, but warm-sounding amplifiers usually suffer from a homogenized smoothness that sacrifices the sharpness of transients. The result can be over-romanticized massed strings that become a congealed, sticky mass, instead of having the more accurate real-life quality of sounding simultaneously "feathery" and edgy, and revealing the fact that multiple bowed instruments are being played.

In my system, the M-800A effectively managed the massed strings of familiar recordings, producing sufficient feathery edge and delineation of individual instruments, as well as a fine sense of the "massed" part of massed strings—the easier part for a warmish-sounding amplifier to produce.

Among the M-800A's best qualities was its reproduction of the human voice—in rich, three-dimensional images that balanced throat and chest sounds with textural suppleness and believability. The intimacy of a new 45rpm, 180gm vinyl edition of Julie London's Julie Is Her Name is truly astonishing (mono, Liberty/BoxStar). Her voice hovers with come-kiss-my-neck believability, backed by Barney Kessel on guitar and Ray Leatherwood on bass. I could "see" London standing behind the microphone—the sound is so convincing, it's what you'd expect to hear before it reaches the mike. This classic of sultry swing was definitely more believable through the Luxman than through my reference amps, which produced a somewhat less vivid, less velvety image of London, though with a somewhat greater volume of surrounding air.

Yet while the M800-A was firmly on the warm side of neutral, it also managed to communicate the obnoxious qualities of bright, spotlit recordings without covering up their character by making them sound pleasant. The Luxman's harmonic presentation was as fundamentally correct as I've heard from any amplifier, tube or solid-state. And in addition to its notable tonal and textural balance, the M-800A developed the sense of "continuousness" I usually associate with tube amps, especially those with tube rectification.

The Luxman produced notably deep, superbly organized soundstages, on which it placed compact, solid, believable images. The stage width was slightly narrower than that thrown by my reference kW monoblocks, especially with familiar live recordings. However, this was a very minor shortcoming.

A big surprise was this 60Wpc amp's ability to reproduce macrodynamics—it seemed to fully render large-scale dynamic contrasts. Side 1 of Lorin Maazel and the Cleveland Orchestra's recording of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess contains some short orchestral bursts that the M800-A managed brilliantly (LP, UK Decca). The sound of dice hitting the stage was reproduced with just the right combination of hard, percussive edges and wooden floor; and the bordello's pseudo-tack piano, while not as well rendered as by my reference amps, had an appropriately metallic tinkle through the Luxman.

For whatever reason, the M800-A did less well with this recording's lowest-level microdynamic details, which it reproduced with a mild sense of compression. While the Luxman was notably quiet and produced jet-black backgrounds, the male chorus's ghostly, nearly whispered singing just before "Summertime" sounded somewhat forward, instead of sneaking up to surprise me as it usually does. Overall, the M800-A's production of low-level dynamic contrasts and its delivery of fine, low-level details suffered somewhat in comparison with the Musical Fidelity kWs. In the big picture, however, this proved a very minor issue. When soprano Leona Mitchell hit her first round, pure, appropriately piercing, nonmechanical note in "Summertime," I got the full measure of the M-800A's rendering of the female voice: stunning.

The M800A remained in my system for several months, during which every kind of music pulsed through it. I ran it both single-ended and in balanced mode using two preamplifiers: the MBL 6010 D (which I reviewed last month) and the darTZeel NHB-18S (which I reviewed in the June 2007 Stereophile). I also ran it fully balanced through Luxman's C-800f preamp, which has been voiced similarly to the M800-A. For my tastes and in my system, I found the Luxman-Luxman combo too smooth and insufficiently detailed. I preferred either the MBL or the darTZeel preamps, both of which are leaner and, to my ears, more detailed. They're also a lot more expensive.

After I'd spent a few weeks noting the M800-A's velvety-smooth overall tonal personality, the solidity of its images, its coherent, stable soundstaging, and—especially—its smooth musical flow, the amp simply blended into the landscape of whatever music I was listening to (though it continued to make its presence known throughout the summer by the prodigious amounts of heat it threw off!).

Back to the Musical Fidelities

When it was time to ship the M800-A to JA to be measured, I reinstated my reference Musical Fidelity kW monoblocks in the system and, after an appropriate break-in period, played some of the same LPs and, via a Sooloos music server, CDs.

The big kWs' soundstage was taller and wider but not deeper than what the Luxman had produced. The MFs' low-level dynamic contrasts were notably more expressive, but large-scale dynamic swings sounded remarkably similar through both, which surprised me. The big kWs produced more air and sparkle on top than the Luxman, but were also somewhat drier overall, less fully realized from top and bottom, and couldn't match the M800A's rich, velvety midband.

Conclusion

At first glance, the Luxman M-800A appears to be an expensive, underpowered amplifier best used with sensitive, easy-to-drive loudspeakers. I found that not to be the case. Its ability to double its power output with each halving of loudspeaker impedance made it suitable for driving even loads as difficult as the Wilson Audio MAXX 2. Still, it would be best to consult the importer before buying, to make sure it's up to the task of driving your speakers.

On a Higher Note's Philip O'Hanlon claims that two M800As run in bridged mode can each deliver four times as much power (240W into 8 ohms), and produce explosive dynamics at both ends of the scale, for a vast improvement in the resolution of inner detail and even greater bass solidity and extension. I believe him! But two of them would cost $32,000, and a single M-800A was already plenty good in all those areas.

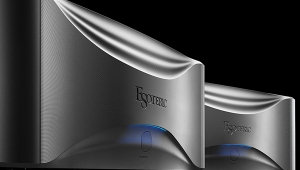

The M800-A's build quality, fit'n'finish, and appearance are up there with the finest I've seen—and its binding posts are among the most convenient and secure I've tried. And unless your system is warm and soggy and you're looking for relief, the M-800A's sound leaves little to be desired. If your system's sound is anywhere from analytical to lean, and you want a touch of sonic cushioning without falling into soft springs, the M-800A may be what you need. It presents its case seamlessly and effortlessly, with no significant negatives other than heat. I never thought I could be satisfied driving the MAXX 2s with such a low-powered amplifier. But I can.

Philip O'Hanlon once imported Halcro amplifiers, which I could respect but never love. I can love and respect the Luxman M-800A—even the next morning.

- Log in or register to post comments