| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Listening #136 Page 2

The new model's vacuum arm moves more slowly, requiring about 70 seconds to traverse an entire LP side. (Older Monks machines do it in just over 50 seconds.) The nylon vacuum nozzle has a new shape, better suited, according to Jonathan Monks, to the slower platter and vacuum-arm speeds. And whereas the thread supply and its spooling mechanism are hidden from sight in the older, more expensive Keith Monks models, the discOveryOne keeps its thread aboveboard. With my own sample, the feeding of fresh thread into the system was not automated—I had to remember, after washing each side, to give the spool a little turn. Having lived, some years ago, with Loricraft's own very fine version of the basic Percy Wilson record-cleaning machine, in which the thread mechanism is also manual, I can say with confidence that that is no big deal.

Footnote 4: The SevenArts pressing looks different, too: Groove spacing is unlike that of the later pressings, and messages are inscribed on both sides' lead-out areas: "Hi, James" and "That's all, folks." The early cover also lacks the superfluous text advertising the singles "Fire and Rain" and "Country Road," although it appears there may be some overlap—ie, pressings made from the later, inferior master whose covers also lack the sales blurb.

As received from the factory, the Keith Monks discOveryOne was a nearly plug-and-play device. After wrestling the cabinet out of its shipping carton—the discOveryOne is, somewhat surprisingly, larger than an original single-platter Monks machine—I needed only to slide the platter and the cleverly designed mat onto the direct-drive spindle; to remove the packing from around the waste-collection jar, which is housed in a compartment toward the left side of the enclosure, accessed through a toggle-locked panel; to remove the packing from around the vacuum arm; and to set the arm's "tracking force" in the usual manner. The last was the only tricky bit: The exit hose of the waste-collection system runs concentric with the arm's counterweight, and must be temporarily disconnected to keep it from fouling the arm's balance.

Behind the greenish door: bottles for spent fluid (left) and fresh fluid are tucked away inside (Photo: Art Dudley)

Although the discOveryOne comes with a handheld nylon-bristle brush, I elected, at first, to use my own short-nap Disc Doctor brush, in tandem with L'Art du Son record-cleaning fluid, which has been my reference for a number of years. I began by auditioning a few random portions of a recent thrift-store find, a complete set of Beethoven piano trios performed by the Beaux Arts Trio (Philips 6747 142): a nice if unspectacular collection, the latter quality evinced by the fact that Philips's cover-art department restricted their efforts to photographing a square piece of green burlap. All four discs were noisy as hell, and a portion of one had a few mild skips; visually, the only remarkable faults were fingerprints—enough to fill a Quantico closet, it seemed.

I followed my usual regimen of applying 3ml of L'Art du Son per side (a little more is required when starting with a completely dry brush) and gently applying the brush to the record while the platter is stationary, using more pressure and lots of back-and-forth scrubbing on the most apparently dirty portions. After that, the discOveryOne's vacuum system dried each side every bit as well as my older Monks machine, notwithstanding the new one's slower speed. In fact, the new machine was much better at removing the fluid from the outermost edge of the record before it could migrate to the other side; perhaps the slower platter speed is to thank for that?

The sound of the uncleaned Beethoven LPs was so awful that I was tempted not to bother; after their trip through the discOveryOne, the sound of the discs ranged between G– and G+, and the skippy side played without a hitch. (One wonders how thick a fingerprint has to be before it causes a stylus to actually exit the groove.)

A title from a record collection I bought last year yielded an even more striking improvement, and an even better story: At some point in time, its previous owner had picked up a used copy of James Taylor's Sweet Baby James, apparently for $1.25. The once-noisy record responded brilliantly to the Monks treatment, and the newly good sound—amazing sound, really—prompted me to do a bit of research. Mine turned out to be an early Warner Bros.–SevenArts pressing of the album, from a different disc master than the comparatively tinny-sounding pressings that followed (footnote 4). Ka-ching!

Soon after, I tried the discOveryOne's optional wet-wash upgrade, which comprises a reservoir jar for fresh cleaning fluid, a manually activated fluid pump (whose plunger proudly bears the original Mini Cooper windshield-washer icon), and an adjustable, swing-away cleaning-brush holder that dispenses fluid evenly across the record. Those bits are included in a model called the discOveryOne Classic ($2995), or can be added at any time to a discOveryOne by means of a user-installable kit ($795).

Coincidentally or not—a proviso I'll return to in a moment—my time with the upgraded machine yielded my best results: Three years ago, after my elderly neighbor Beek passed away, his family gave me a bunch of his records, including my prized copy of Charlie Parker's New Sounds in Modern Music Vol.1, Deutsche Grammophon recordings of Berg's Wozzeck and Lulu, a couple of Hoffnung collections, and, most promisingly, the original mono recording of Grieg's Peer Gynt Suite by Sir Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic (EMI ALP 1530). The wonderful laminated cover of the Grieg was intact, but the record itself sounded damaged beyond help. That "damage" proved to be dirt—dirt that gave in to a proper Monksing, with the brush physically aligned for a fairly stiff scrubbing, and using the latest version of the Keith Monks discOvery33/45 cleaning fluid, which very obviously contains vinegar. The Grieg is now quite listenable overall, with most portions sounding utterly new.

Faith in things uncleaned

I don't mean to waterboard a dead detainee, but the fact remains: To offer a truly definitive review of any record-cleaning product or regimen is next to impossible. Records aren't like dirty dishes or soiled clothes. The dishwashing liquid that does a superior job of dissolving burnt lasagna from casserole dish No.1 is very likely to do the same for No.20, and the detergent that removed the grass stains from your left sock is sure to do the same trick for the one on the right. But phonograph records can't be compared in the same manner, because no two can be presumed to be soiled—or damaged, for that matter—in the same manner or to the same extent.

And my disdain is well known for reviews in which the writer cleans a record with Product A, listens, cleans the same record with Product B, listens again, and then, on hearing an improvement, declares that B is superior to A. There exists a very strong possibility—some would call it a likelihood—that a second cleaning with product A would have produced the same result.

I can't know, but I can and do believe that some cleaning products and regimens are superior to others. Based on decades of collecting records, trying and buying various different cleaning products, and writing about phonography, I endure in the belief that a wet-wash, vacuum-dry machine in which the vacuum drying is accomplished with a thread-cushioned pivoting arm is the best way to do the thing.

So, yes: I'm impressed with the Keith Monks discOveryOne, simply because it cleans records every bit as well as the considerably more expensive Omni RCM Mk.VII—or any number of similar alternatives. The discOveryOne isn't as efficient as the Omni, nor is it quite so pleasant to use: The Omni is quiet, solid, well-made, and looks purposeful; the discOveryOne, while similarly quiet, isn't quite as solidly built, and portions of its cabinetry are held together with wood screws driven straight into rather thin pieces of dry hardwood, sometimes at angles that are less than straight-on. The toggle lock on its access door is a bit flimsy, with no structural element in place to limit the door's inward travel, and the dustcover—essentially the one that would have come with the Citronic turntable, and which does not cover the entire top of the machine, and is not held in place with hinges or by any other means—seems inadequate.

Still, for a machine of proven effectiveness to sell for less than half the price of its stablemates is a hell of an accomplishment, so I'm disinclined to quibble. The Keith Monks discOveryOne will be added to "Recommended Components" as an accessory of notably high value—and notable worth. Not only should this product be considered by any collector in possession of more than a couple thousand titles, but anyone who spends more than a few hundred dollars a year on low-price used vinyl should give it a serious look—before long, KMAW's new entry-level machine could pay for itself.

Iron-core porn

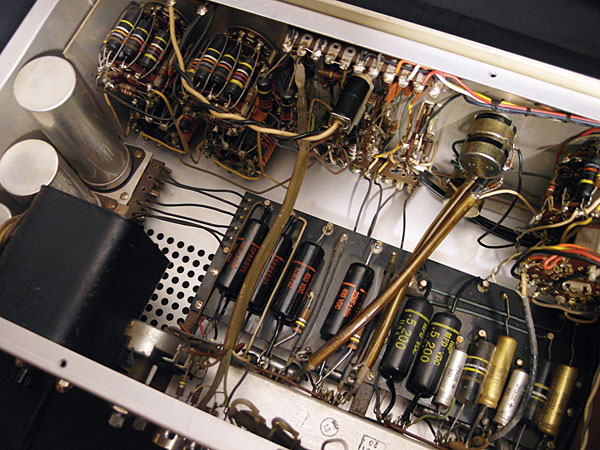

I close this month with a few photographs that amount to little more than pornography, God love it. This Marantz 7 preamplifier, built in 1964, was recently discovered in a multi-dealer antique bazaar not far from where I live, in upstate New York. (You do not want to know the price for which it was purchased. Take my word.)

A 1964 Marantz Model 7 preamplifier, recently restored (Photo: Art Dudley)

Many of the original Telefunken tubes were in place and tested surprisingly well, and the selenium rectifier stack at the heart of its power supply was also fine, but several capacitors leaked DC and needed replacing; local technician Neal Newman installed period-correct replacements, and did an amazing job of cleaning away a half-century of grime. Before it was shipped off to its new home in California, I listened to the 7 through Quad ESL speakers and was reminded anew of why vintage Marantz gear is held, throughout the world, in such high regard. And, as my British friends would say, it certainly looks the business.

The same preamp, seen from the rear (Photo: Art Dudley)

Inside the Marantz 7: "Don't be vague, ask for Sprague!" (Photo: Art Dudley)

Footnote 4: The SevenArts pressing looks different, too: Groove spacing is unlike that of the later pressings, and messages are inscribed on both sides' lead-out areas: "Hi, James" and "That's all, folks." The early cover also lacks the superfluous text advertising the singles "Fire and Rain" and "Country Road," although it appears there may be some overlap—ie, pressings made from the later, inferior master whose covers also lack the sales blurb.

- Log in or register to post comments