| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I'd be disappointed, and call that book incomplete. Yamaha, Luxman, Sansui, Pioneer and Kenwood were all competing for high-end credibility, too.

Thanks very much for the review!

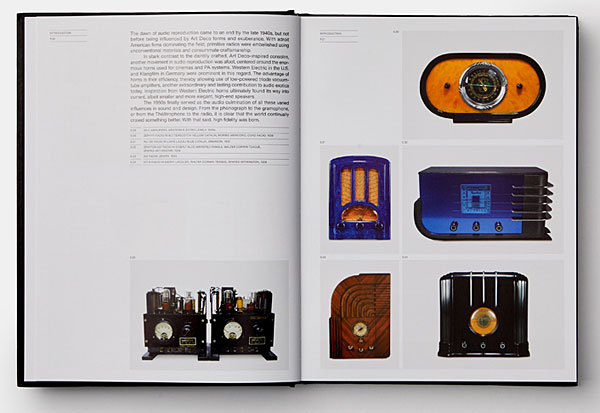

The ongoing evolution of hi-fi can be measured in any number of ways. Most obviously, we see that evolution in the technologies associated with our industry: in big breakthroughs—mono to stereo, tubes to transistors, analog to digital—as well as incremental improvements in materials and manufacturing techniques. Those and other refinements bring with them changes in sound quality—hopefully, but not always, improvements—but no less important to the industry are changes in form and design, which mirror developments in art, aesthetics, and fashion.

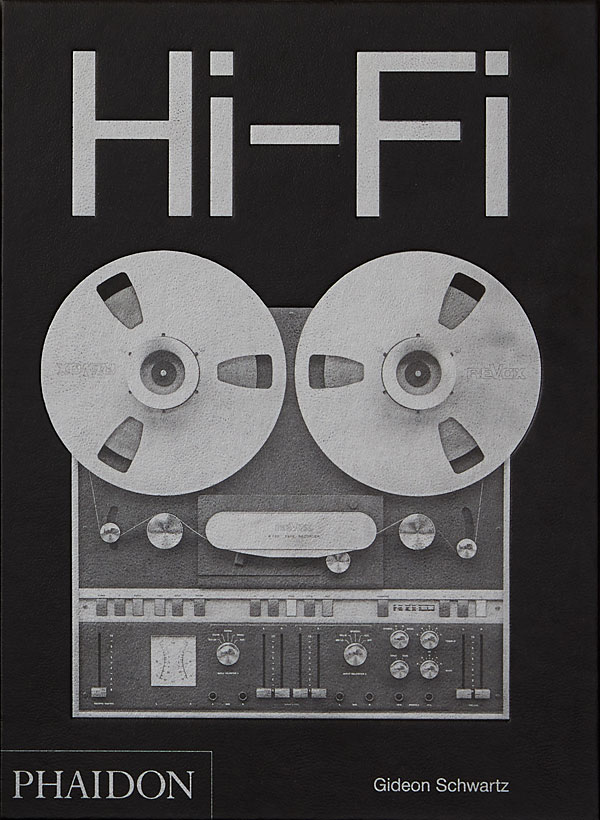

Audio's changing forms is the subject of Hi-Fi, written by Gideon Schwartz—proprietor of New York City–based audio salon/distribution company Audio Arts—and published by art-book specialists Phaidon, with photos collected from a wide variety of sources. Hi-Fi tells the story—or at least a story—of its titular industry, in mostly well-chosen words and stunning photos.

Hi-Fi offers well-known stories and conventional wisdom, especially in depictions of companies and industry figures, but there are some surprising insights. Did you know that the first music-streaming service started in Paris—during the 1880s? Schwartz introduces us to Clément Ader, a self-trained French inventor who filed a patent in 1881 for what he called the "Théâtrophone," which broadcast music and other performances out to listening stations and homes over phone lines. The technology was exhibited at the first International Exposition of Electricity, which was held in Paris. It was heard there by Victor Hugo. Schwartz writes that Marcel Proust heard it and signed up. The Théâtrophone was a success in Paris and got a foothold in some other European cities. Coming as early as it did, the Théâtrophone was not only the first music-streaming service: It was also, Schwartz writes, the source of "the first domestic audio replay." It wasn't a flash in the pan, either. Théâtrophone hung on for decades, fading only when the first form of wi-fi—radio—rendered it obsolete.

By the way, in the very same 1881 patent application, Ader invented stereo. You can read all about it in Schwartz's book. Schwartz's understanding of the culture of high-end audio first becomes apparent on p.13, where he writes, "Edison's phonograph was a purist's dream. Recording and playback could not have been more closely intertwined." Vibrations were recorded on Edison cylinders via a simple mechanical device and read the same way, inverted. Among audiophiles, that kind of immediacy has meaning. Those today who seek high-efficiency single-driver speakers, simple tube amps, and low parts counts would understand.

However, the simple Edison cylinder was soon superseded by another simple technology: the gramophone. And in Switzerland, music-box maker Thorens soon launched its own version of both machines. "Unquestionably Swiss in its micro-precision, sophistication, and elegant functionalism, the company forged the philosophical substrata for all of the country's future audio firms, as well as paving the way for companies worldwide," Schwartz writes. Schwartz understands us.

By p.18, Schwartz is already up to the 1930s and the creation of the first Zellaton loudspeaker, with its cones made from foil-covered lightweight foam, a construction technique that became an industry standard. (The German company Zellaton is still around—in fact, Schwartz is a Zellaton dealer. Two of the company's recent loudspeakers are pictured on p.248 of Hi-Fi.)

The 1950s were, to Schwartz, a decade of "Industrial Stereo Utopia." "This industrial emphasis on quality was unique," Schwartz writes, "since it was unencumbered by later influences such as cheaper manufacturing, Asian imports, planned obsolescence, and creative marketing. It is fair to say that the seeds of high-end audio were firmly planted in the 1950s, and these would yield the cottage high-end audio industry that occurred during the 1970s."

Hi-Fi is mainly about audio components as physical objects, and the 1950s "introduced the world to bold simplicity and uncluttered virtuosity in industrial design," taking cues from Modernism, Schwartz writes. New technology was paired with "austere functionalism," starting a design trend that continues today. Illustrating this trend are photos of Braun products from Dieter Rams and Hans Gugelot, familiar-looking turntables from EMT, Garrard, and Thorens, components from Fischer, Leak, and Marantz, and loudspeakers from Quad and Acoustic Research.

As he browses the decades, Schwartz injects quasi-technical discussions on the nature of sound and philosophical disquisitions on "The Truth About 'Faithful Reproduction,'" which lay out the debate between those who want accuracy and those who want beautiful sound.

The 1960s, for Schwartz, were the years when stereos got sexy. Hi-fi was accepted into the mainstream. New, less techy approaches proliferated. "The hi-fi became an aspirational product as portrayed in films and literature of the time—particularly among younger and more affluent single men." Hi-fi coverage escaped from audio-geek journals. Playboy perpetuated the idea that every man needs a stereo system and included reviews of new audio components.

But in the 1960s, the industry's economics were also changing. Even as America's collective wealth grew, and more people entered the hi-fi marketplace, price became more of a consideration, not less. Marantz found it couldn't make a profit on perfectionist products like its 10 B stereo tuner, undoubtedly the best of its day. Manufacturing shifted from an industrial aesthetic toward mass production. Newer, cheaper materials were used, not only plastic but also silicon. "Many of the early manufacturers that embraced solid state in the 1960s were not compelled by sound quality, as tube designs of the day actually offered superior fidelity," Schwartz writes.

Still, gorgeous audio objects were created then, including stereo consoles from Clairtone—I want one!—the aforementioned Marantz 10 B tuner, components from McIntosh, and loudspeakers from Bose, Klipsch, and Tannoy, plus the astonishing JBL Paragon loudspeaker by Arnold Wolf (p.83).

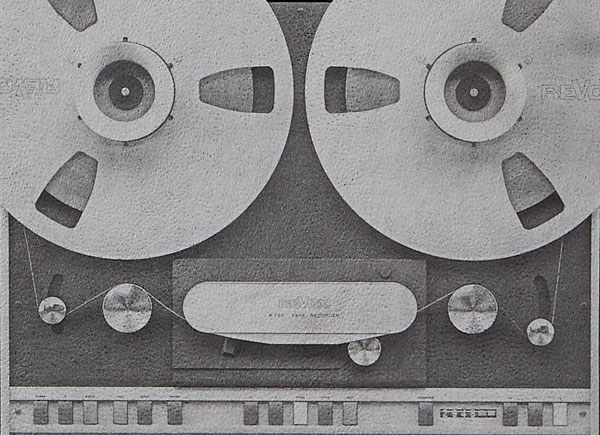

Schwartz describes the 1970s as the decade of "The Birth of High-End Audio," commenting that it "would not be entirely inaccurate" to "label the 1970s as an analog elysian fields." That may be, but this is where the text starts to lag: It seems that there's both more to say—more companies to write about—and also less: fewer compelling story lines. After spending several pages on tape—reel-to-reel and cassette—Schwartz moves on to discuss Mark Levinson, Audio Research, Threshold, Linn, Naim, B&W, and the first Magnepans and Infinitys, briefly telling each company's story and showing some of their products from that era.

For Schwartz, the 1980s was the decade of "High-End Audio in Full Bloom." Electrostatics and ribbon speakers come into their own. There's even a company I didn't know about: Swiss Physics. Founded by Mauro del Nobile, Swiss Physics housed its components "in piano-finish lacquered wooden cabinets, and to match the exterior's execution, the interior technical layout was pure Swiss beau idéal."

And then it's on to the compact disc player in its various guises, and then to the earliest DACs.

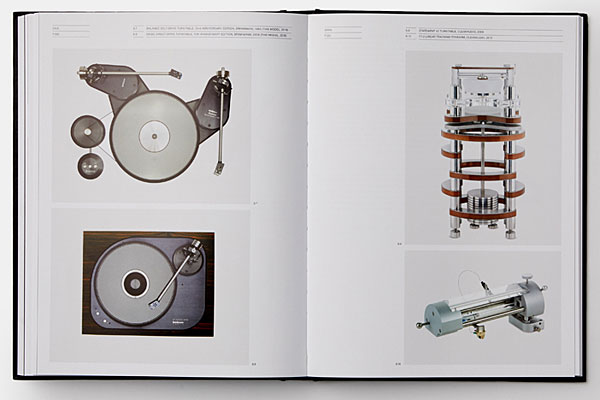

The theme of the 1990s for Schwartz was the "Return of the Vacuum Tube," featuring amplifiers from Kondo, Audio Note, Jadis, Lamm, Conrad-Johnson, and Fi; horns from Avantgarde and Acapella; and dynamic loudspeakers from Wilson, Sonus Faber, and Celestion. By the time we reach the final chapter, dubbed the "Post-Digital Analog Renaissance," the text is little more than a series of capsule profiles of the various audio companies—but the photos here document some of the most visually compelling designs in the book. There's turntable porn from Artisan Fidelity—their modified version of the Garrard 301—and Clearaudio: the Statement and its TT-2 Linear Tracking tonearm. There's a stunning shot from above of a Brinkmann Balance 'table, and a head-on shot of the magnificently odd R-evolution Meteor Stealth from Serge Schmidlin and Audio Consulting. Several pages cover cartridges, with photos of pick-ups from Koetsu, Miyajima, and Ortofon.

The book ends with half a dozen pages of tasty designs from our era, from Soulution, Magico, Zellaton, Thîress, and others.

Hi-Fi is a quick, easy, read—especially engaging in the earlier part, from eras when the industry was less crowded and with more room for longer, more engaging stories—with photos you'll want to linger over. It's true that, with patience, you could probably discover most of these images and more on the World Wide Web—but who wants to do that? Recommended, for solid writing, much of it interesting, and circa 300 well-reproduced, mostly color images.

I'd be disappointed, and call that book incomplete. Yamaha, Luxman, Sansui, Pioneer and Kenwood were all competing for high-end credibility, too.

Thanks very much for the review!

My mom owned a Magnavox console with a Benjamin Record- Changer ( could even play 16rpm. ), she was a performing soprano that rehearsed at our Detroit Home. I would come home for lunch, find out the Magnavox wasn't playing records and have it back up for that evening's rehearsals.

Mom's favorite Radio program was Adventures in Good Music by Karl Hass. So I had to maintain a functioning AM Radio Section of that Magnavox.

My mother never thought of herself as an audiophile but her 100% devotion to performing and listening has remained imprinted in my Synapses ( and pretty much all my children ).

For all these decades of Audio involvements I'd have to say that Audio's Greatness came when :

No.1) KEF build those magnificent LS3/5a drivers

and

No.2) Koetsu created it's outstanding Rosewood ( along with the rest of their range )

I have the feeling that the 1980s brought all the greatness that Analog will ever bring, which is plenty enough to keep a person's brain releasing ample dopamine when listening to the better recordings we had available.

Portability and Class D amplification are part of what makes Digital such a dominant format.

Audiophiles are in for a delightful future absentia the encumbrance of clumsy 33.3 with all of it's playback cult ritual.

Tony in N.H.

ps. I would buy my mother that Devialet Loudspeaker, she'd be thrilled.

Here is a link to an interview with Mr. Schwartz. He has a nice philosophy about music and hi-fi and is not a snob.

https://ca.phaidon.com/agenda/design/articles/2019/december/04/interview-gideon-schwartz-on-the-rise-fall-and-rise-again-of-high-end-hi-fi/

"Schwartz describes the 1970s as the decade of "The Birth of High-End Audio". Please excuse my ignorance,but if this is true, what of earlier times? JGH started the mag in 1962(same year I was born).Wasn't that High-End Audio? What am I missing?

I believe the term high end audio was only coined during the 1970s. Before that, everything was high end. In terms of purchasing power of the day, pretty much all audio equipment sold during the 1960s would qualify as high end. In fact, buying a table radio during the 1950s involved major financial outlay for a household. It was only during the 1970s that the Japanese started producing mass market audio equipment. The term high end was therefore coined to distinguish the "serious" gear from mass produced products.

The cost of LPs also followed the same path. The RCA Living Stereo, Mercury Living Presence, Decca SXL2000s of the early stereo era would cost a substantial chunk of someone's weekly income.

Hence, we still listen to these LPs, as well as use the old Quads, Leaks, Tannoys, Marantz, Macintosh, JBL, Altec etc. from the 1950s and 60s quite happily nowadays. If those were not high end, what is ?