| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

This is a spiritual-political masterpiece - and easily the best writing ever published in an audio magazine.

It was awful. In particular, it was impossible to toast just right: it was too thick, too doughy, just plain too big. I had learned a valuable lesson: Talking myself into wanting something isn't a good enough reason to actually buy it.

That lesson lasted until the next time I saw Thomas's Sandwich Size English muffins in the supermarket. I couldn't help myself. I thought, This is it: the perfect English muffin. I convinced myself that there must have been something wrong with that first batch. Or maybe I just hadn't tried hard enough to toast them properly: Obviously, the idea behind the product was perfect. So I bought them. And they, too, were awful. Once again, I'd learned my lesson.

Until the next time I saw Thomas's Sandwich Size English muffins in the supermarket. I thought, This is it: the perfect English muffin, and if there's something wrong with them, it's my fault, and I have to adapt. So I bought them.

This is how the minds of some audiophiles, myself included, tend to function.

But that's immaterial

Show me a hobby that revolves around consumer goods that most people consider nonessential, and I'll show you a hobbyist who believes there is no problem so great than it can't be solved by spending more money.

That's fine with me. I have nothing against capitalism, as long as it's sufficiently well regulated that children, the elderly, and the mentally unwell are protected from the Keatings and the Madoffs (and their families) who would steal and squander their last dollar, and as long as the currency to which the system is pegged is itself subject to reasonable protections. That said, one could argue that capitalism is a system in which seemingly wasteful purchases are inevitable, inasmuch as capitalism is a system in which the evolution of marketing strategist as a career choice was inevitable.

I no longer think that's a terribly big deal. In my youth, I was a scruffy, longhaired folkie who sang songs that extolled sharing and refuted the materialism of my elders. Naturally, there came a time when it dawned on me that those songs sounded better and were easier to perform when accompanied by a nicer—and more expensive—guitar, on which day sanctimony and I parted company. Thus ensued my own evolution: I turned into someone who believes that, up to and excluding expenditures that confound personal responsibility and/or are excessive to the point of obscenity (footnote 1), there is nothing wrong with owning something that makes you happy.

Of course, that can go terribly well or terribly wrong. In the latter category we have the Imelda Marcos shoe collection, the Thurn und Taxis jewelry collection, the Sultan of Brunei's automobile collection, and Graceland.

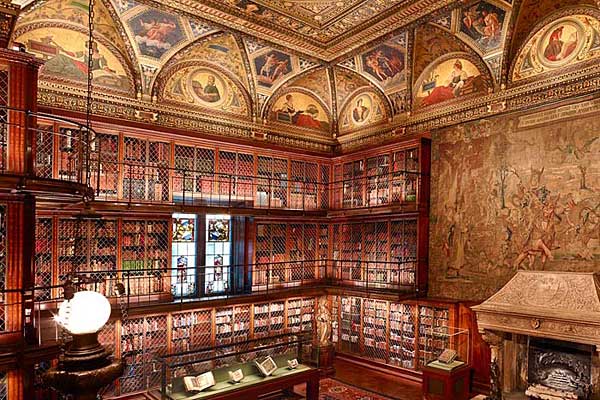

But when things go well, we get the Cloisters, the Frick Collection, and the Morgan Library & Museum (footnote 2)—to name just three jewels in Manhattan's crown. I mean that literally: We get them. All human beings who are free to travel without restriction and who can afford the modest price of admission are allowed to enjoy those tapestries, illuminated manuscripts, paintings, statues, rare books, and other collectibles, thanks to various generous people of privilege and their descendants (footnote 3). And that's not to mention the many wealthy collectors who loan, often indefinitely, their priceless violins, violas, and cellos to the best performing artists of the day.

Generous wealthy people with good taste and an appreciation for the arts: they do materialism right.

Let's get physical

So where does that leave collectors of LPs and 78rpm records? And what about those music lovers who've given up on physical media altogether, in favor of downloads and streaming? Is this a case of crass, old-world materialists vs those who would liberate works of art from their physical—and thus, to some extent, commercial—restraints? I know a few folks who share both of those points of view, but I don't think things are quite so simple. Consider that generous record collectors have made possible countless numbers of digital remasterings of rare recordings. Consider also that, in some genres, musicians whose livelihoods traditionally depended on back-catalog sales of their albums—and not just 99¢ downloads of singles—have been driven to the brink of financial ruin by the retreat from physical media.

And who really thinks that doing away with bricks-and-mortar record stores is anything but an awful idea? Sure, for some music purchases, downloading is great, just as buying physical media online can be great. But to buy all of your music via computer—as when able-bodied people order-in all their groceries and books and clothing and stuff—seems just a little bit off, in that Sunset Boulevard, keep-the-drapes-closed-all-day kind of way.

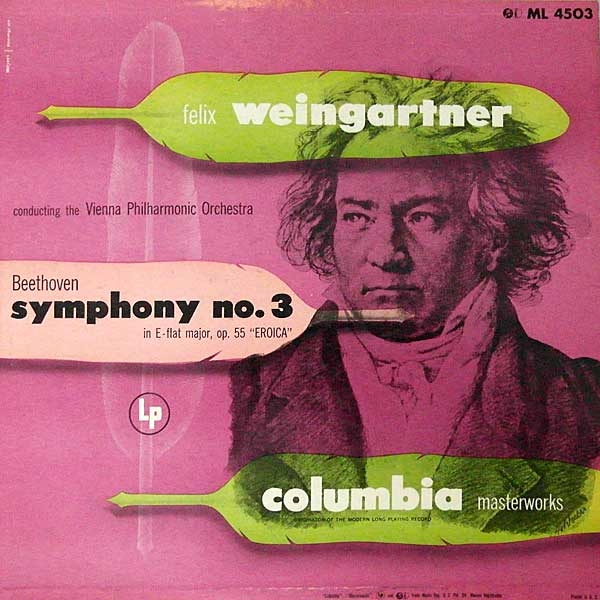

When talk turns to the debate between owning music on physical media and owning-but-not-really-owning music in download form, my mind wanders to a place and a time—Yonkers, New York, in the mid-1980s—when I discovered a used-book store that, for a while, also did a brisk trade in used classical LPs. Over the course of several months I began to lighten their inventory, a few records at a time, and I soon noticed a pattern: Many of the records I bought there came from a single collection whose original owner had stamped their jackets and boxes with his name. John Alan Hunt had obviously taken very good care of his records, and as a bonus had marked each one with the date he purchased it: a nice bit of context, especially for someone like me, who was, at the time, very new to the world of classical records.

Then, one day, I discovered another bonus: Among the John Alan Hunt titles I'd bought was Toscanini Conducts Wagner: two LPs packaged with a four-page booklet in a sturdy box decorated with Wagner's profile, embossed on a metalized sticker. As with many such multi-disc releases, the box also contained a 12"-square piece of corrugated paper, to take up space that might otherwise have accommodated another disc or a thicker booklet. (Not to be unpleasant, but as I came to realize over the years, there is just so much one can say about Toscanini's conducting style.) It wasn't until a few years after I'd bought that set that I happened to remove the corrugated paper—and discovered that John Alan Hunt had tucked behind it every newspaper clipping he could find that noted Arturo Toscanini's death, in January 1957. (According to Hunt's notation, he bought Toscanini Conducts Wagner in March 1955.) That sent me looking through other records I'd bought, second-hand and third-party, from John Alan Hunt, and hidden away inside some I discovered obituaries of other musical artists. Which was very, very cool.

That discovery altered my course, as a collector, in a couple of different ways. First, it led me to take up John Alan Hunt's "work" for myself—beginning in 1987, when I clipped from the New York Times the obituary for Jascha Heifetz and tucked it inside the boxed version of his 1959 recording of Beethoven's Violin Concerto. I don't know who'll have my records 30 or so years from now—whether my daughter or my friends or someone I've never met—but whoever it is, I hope they'll enjoy the ongoing necrologue.

Footnote 2: Just two blocks down the avenue from Stereophile's offices.

Footnote 3: Things can go nicely or things can go wrong, but things can also go weird—witness materialism's third stream, hoarding, pioneered by the infamous Collyer brothers, also of Manhattan.

This is a spiritual-political masterpiece - and easily the best writing ever published in an audio magazine.

Normally I'm not really big on bling, but the local Louis Vuitton store had an iPhone 7-plus case made to look like their steamer trunk, for only $1300 USD. I can't afford a Lambo, nor can I afford a $55k Sennheiser Orpheus, but I have a $1300 iPhone case, and my less-than-well-off friends are in awe of it.

On a more directly musical note (albeit my phone is my primary digital transport), I purchased a Mont Blanc "Miles Davis Edition" ballpoint pen for $770 today, and it's a beautiful pen with the pocket clip fashioned like a trumpet's valves. Makes a great gift!

Your purchases clearly demonstrate an astonishing level of refinement.

For most people, an ostentatious item would either be the outrageously expensive item that only the elite can afford, or a more common item covered in diamonds or gold. I had such an item, a Rolex President that I wore for 8 years, and while it was a great business investment, it has no purpose in my retirement.

Maybe I can help with two greetings, but it's hard to say for sure from this picture:

Nojserolecruij zre zyczenia—Misie - Najserdeczniejsze życzenia means something like - heartiest/warmest/best wishes - for name I'm no sure. It could be - Misia or Miecia,

Hedwig Imuilewski - it looks for me more like - Ludwig Chmielewski. But it's really hard to say from above picture.

Well said Art. But as a fellow LP collector* how could I disagree?

*It's nice to hold an album in hand, but the real reason is to hear the music.

Terrific piece, Art. I've enjoyed your work for many years, particularly your sense of humor. You manage to display your passion for our hobby without taking it too seriously. Like many subscribers to your magazine, I'm basically old school, pursuing my music listening on LP and CD. Downloads? Streaming? Never touch the stuff. The so-called "cool" factor in hi-fi via Playboy Magazine escaped me. It's the passion for the music and the gear, in that order.

What if we paid more for the services we receive? Just as benefactors supported artists, should golden- eared audiophile writers be financially preserved to entertain and guide us? We should acknowledge the time and money critics save us. And clearly, its important that your family has bread on the table.

Should we crowd fund our future guides like Stephen Meijas who has kindly returned? Stereophile is almost free now, how can he earn a living wage from subscriptions? Will advertisers step up?

Please teach him to squirrel away beautiful physical media to sell in the inevitable lean years. Just as I bought obsolete vinyl, I now buy CDs from thrift shops, especially those with beautiful hand made covers and artistic label prints. They fund my hifi habit a little, but I did have to learn to bake bread in my retirement.

Thank you for contributing to great journalism, and alerting us to threats to our lifestyle.