| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

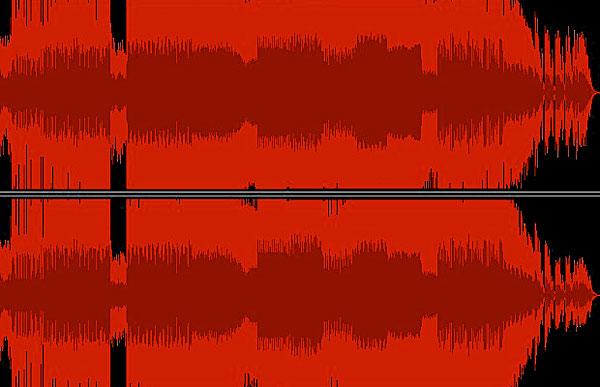

No natural sounds in life are compressed, why do it to the music we listen to.

Uncompressed music gives you space between the notes, these days everything is the same level (no space!!).

I believe it's done so Ipod etc users don't blow their eardrums or earphones up when dynamic transients are produce, because they would turn up the volume during uncompressed quite passages.

Cheers George (I hate compression of any sort, it should be banned)