| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

If it's between today's commercially viable, autotuned, dynamic-smashed sound, or musicality, I have no need to suffer contemporary tastes. The many decades of 20th century recordings, most of which I have yet to hear, I will enjoy without missing the current commercial oeuvre at all.

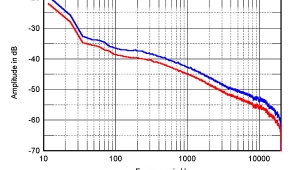

To suggest compression is about normalizing levels among tracks is a strange tack, at best. Radio station processing chains have been doing that for at least 50 years, and probably inured most to the absence of dynamic range.

Now excuse me, I have some listening to do. Those Edison cylinders are around here somewhere.