| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

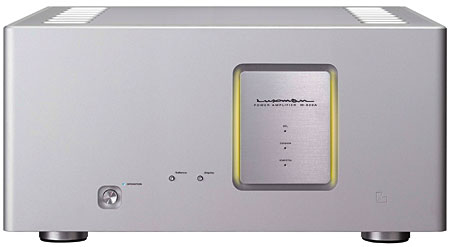

Luxman M-800A power amplifier

Founded in 1925, Luxman has long been one of Japan's most highly regarded audio manufacturers. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, Luxman's tube preamplifiers and power amplifiers occupied the top shelves of high-performance audio retailers, and to many older American audiophiles, the Luxman name is as familiar and esteemed as those of such storied American brands as McIntosh and Marantz. Luxman's combination of rich, warm sound, superb build quality, and indelible industrial design made its products fully competitive with other brands then considered among the world's best.

But, as with McIntosh and Marantz, Luxman was the subject of a series of unfortunate sell-offs and acquisitions that seriously wounded the Luxman name. In fact, Luxman and McIntosh both ended up being bought by makers of car stereos: McIntosh by Clarion, in 1990; and Luxman by Alpine, in 1984.

While McIntosh merely floundered, Luxman nearly went under, as Alpine dragged the brand name into mid-fi hell. A subsequent buyout by Korean giant Samsung was another giant step in the wrong direction, both financially and culturally. Happily for audio enthusiasts, private equity groups rescued McIntosh and Luxman in the early 2000s, allowing them to flourish while returning to their original mission statements. In Luxman's case, the engineering team's loyalty through the dark days allowed the company to introduce, in 2005, two products that had long been planned to celebrate the company's 80th anniversary: the C-1000f preamplifier ($30,000) and B-1000f monoblock amplifier ($48,000/pair).

The more recent M-800A stereo amplifier reviewed here ($16,000), and the matching C-800f preamplifier, are trickled-down versions of those highly regarded "80th Anniversary Commemoration" products. Still, $16,000 is hardly chump change, and 60Wpc into 8 ohms sounds like too few watts for the buck, no matter how well built the M-800A might be.

Build quality worth talking about

Weighing a hefty 107 lbs, the relatively compact (17.25" W by 8.8" H by 19" D) M-800A is among the most densely packed pieces of audio gear I've seen. It's also among the most tastefully and elegantly wrapped (the heatsinks are enclosed). The visual highlight of its thick, satiny faceplate is a "floating" aluminum inset with three tiny status lights, labeled, from the top down, BTL, Balance, and Stand By. Two defeatable uncalibrated bargraph power meters, comprised of yellow LEDs, nestle in the vertical grooves between faceplate and inset. A Standby/Operate switch dominates the main panel, which also includes a Display mode switch and an input selector that switches between single-ended and balanced modes.

Dominating the rear panel are two pairs of oversize, vise-like speaker terminals that can accept bare wires, bananas, or spades, and lock them more securely than everything other than the binding posts made by Cardas and maybe a few others. There are also pairs of RCA singled-ended and XLR balanced inputs, a main On/Off switch, a Bridge Tied Load (BTL) switch for bridged-monoblock operation, a ground lug, a 12V DC trigger, and an IEC AC jack. There's also a Line Phase Sensor button that's similar to the old—and very useful—Namiki Direction Finder. This lets you know if the live and neutral AC wires have been reversed at the wall socket. (It happens more often than you might think.)

A peek inside the M-800A reveals Luxman's obsession with build quality and their attention to the smallest details of fit'n'finish. The 16 output devices per channel are mounted to a large copper plate attached to each ample heatsink, to better dissipate the prodigious amounts of heat generated by this class-A amplifier.

If you visit the website of Luxman's US distributor, On a Higher Note, you can see close-up photos of these and other details of design and construction that make clear the attention paid by the designers. For instance, the Luxman engineers claim that an audio component's sound can be smeared by the green solder-mask dye seen on the surfaces of most printed circuit boards, and used by manufacturers to identify signal traces and the placement of resistors and other board components. They've come up with a material that can be peeled off the PCBs once the signal-path traces have been applied and the mounting holes punched. Gold plating of the PCB traces reduces resistance and prevents corrosion. Copper bus bars directly connect the power transformer's output to its storage capacitors, attaching with copper screws. Even the AC jack has been subjected to listening tests, with the result that Luxman uses solid brass plated with nickel, in turn plated with gold. Can you hear the difference? Anyone who's experimented with various plating materials on adjacent AC wall jacks will tell you, with absolute certainty, "yes."

Beauty without the Beast?

The greatest theoretical sonic advantage of class-A biasing, in which the output device's base current is set to permit constant current flow, is the absence of crossover distortion: instead of the upper and lower output devices each switching off every half cycle at the 0V level to hand over to the other (class-B operation), both output devices are always on. The downside is inefficiency and a tube-like production of excess heat. The usual result: a great-sounding, low-powered amplifier that runs very hot.

So while I was surprised when Philip O'Hanlon, founder of On a Higher Note, suggested I pair the 60Wpc M-800A with my Wilson Audio Specialties MAXX 2 loudspeakers, I wasn't at all skeptical: The Bow-Tied One also owns a pair of MAXX 2s, and his listening space is much larger than mine.

But how could such a low-powered amplifier effectively drive the Wilsons? In his "Measurements" sidebar accompanying my review of the MAXX 2s in the August 2005 Stereophile, John Atkinson found the Wilsons to have a sensitivity of approximately 89.7dB, and to be a "demanding load" of 4–6 ohms throughout most of the audioband, with a minimum of 2.25 ohms at 240Hz. They also combine a low impedance of 3.8 ohms and a capacitive phase angle of 33.4° at 162Hz, where, he noted, music has "considerable energy," and which therefore would require an amplifier "that can source a good amount of current."

Somewhat unusually, the M-800A's 60Wpc output into 8 ohms doubles to 120Wpc into 4 ohms, 240W into 2 ohms, and an amazing 480W into 1 ohm. In other words, the M-800A should love the MAXX 2s. And it did. The more punishing the load, the more power the M-800A delivered.

So after I'd pontificated, in my review of Musical Fidelity's 550K Supercharger power booster in the September 2007 issue, about the need for a lot of power in order to reproduce wide dynamic swings, Luxman's M-800A has demonstrated to me that there's more to the issue than pure power. How and where an amp delivers that power also count, and the nominally 60Wpc M-800A was more than up to the task of delivering to the Wilson MAXX 2s enough power to make them sing sweetly and authoritatively.

Class-A sound

My reference Musical Fidelity kW monoblocks are exceedingly open, extended, transparent, and dynamically unconstrained, but they can sound a bit cool, and perhaps a tad thin, depending on the associated gear and, of course, the recording. I learned that while reviewing Musical Fidelity's kW750 in December 2005, which, even at $10,000 (last time I checked), I still regard as one of the bargains in high-powered stereo amplifiers.

- Log in or register to post comments