| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

So many classic tracks that featured Wardell Quezergue's work.

On Tuesday, Wardell Quezergue one of the greatest of them all, the muscle behind much of the now classic R&B that came out of New Orleans in the 1950’s and 60’s, died of congestive heart failure at East Jefferson Hospital in NOLA at the age of 81. Quezergue (pronounced Ka-ZAIR) had a special gift for writing horn charts. He also had a gift for injecting what would come to be known as “funk” into tunes. Some of the hit singles he worked on include such iconic New Orleans R&B tunes as “Iko Iko” by the Dixie Cups, “Big Chief,” by Professor Longhair, Barefootin’ by Robert Parker and “Mr. Big Stuff,” by Jean Knight among others on labels like Nola, Soulsville, Whurly Burley and Shagg. He worked on albums like Paul Simon’s There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, Dr. John’s Goin’ Back To New Orleans and what is undoubtedly the Neville Brothers best album, Fiyo on the Bayou. Along the way he also worked with The Meters, Willie Nelson and Stevie Wonder.

In the 1940’s he played trumpet in the New Orleans band of the great NOLA R&B bandleader Dave Bartholomew before enlisting in the army just before the Korean War. During the war he stayed in Tokyo leading bands. When the person who took his place in his unit died in combat, it inspired him to write a classical piece, “A Creole Mass” which he finally finished in 2000. The composition of that piece may be one reason behind the very dumb nickname, “The Creole Beethoven” that many media outlets used in stories about his passing.

When he returned to New Orleans from the army, Bartholomew hired Quezergue as a staff arranger at Imperial Records in New Orleans where he worked on records by guitarist Earl King and pianist Fats Domino. He also formed a band The Royal Dukes of Rhythm. In the 1960’s he was a partner in the Nola label which released records by funky pianists Willie Tee (who died in 2007) and Eddie Bo (R.I.P. 2009). In 1970’s he put the Malaco record label on the map thanks to “Mr. Big Stuff” and “Groove Me” (by King Floyd) which he made in their Jackson, Mississippi studios and released on their label. Both tunes were later licensed to Stax and Atlantic records respectively.

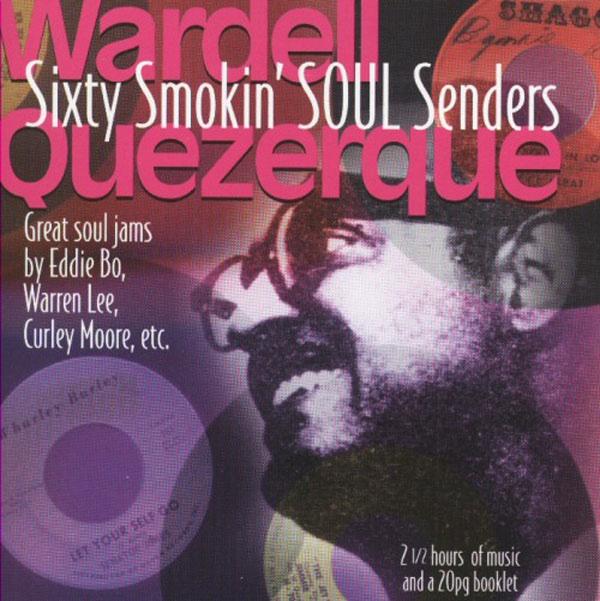

Unfortunately, his final years were filled with controversy and sadness. Diabetes took his eyesight about a decade ago and Katrina destroyed his home and his collection of musical scores in 2005. And yet Quezergue continued to find joy in teaching music to children at St. Mary’s Academy in New Orleans and a 2009 tribute concert for him at Lincoln Center in New York brought him some long overdue adulation. In more recent years, he had had serious financial problems. Arrangers routinely make more money for others than they do for themselves. He’d also been involved in a bitter and protracted lawsuit with Aaron Fuch’s Tuff City Records and associated management company, both based here in New York, over rights and royalties owed from the sampling of the Quezergue/Smokey Johnson song, “It Ain’t My Fault” by hip hop artist Silkk The Shocker. The suit was finally settled earlier this year. Those who are interested can hear both sides of this nasty dispute by reading, “Who’s Fault Is It” by editor Alex Rawls on the website of the New Orleans music magazine Offbeat and the really unfortunately titled, “Tuff City Settles Suit. Wardell Quezergue Emerges as the Biggest Loser” on the home page of the Tuff City website. The image that appears with this entry is in no way a comment on who was right or wrong in the suit. The simple truth right now is that Tuff City and its associated labels are the main source for recordings of the music Quezergue’s arranged and in some cases wrote and/or produced. At Jazzfest this past year, during several pilgrimages to the Louisiana Music Factory I picked up an LP copy of Wardell Quezergue, Sixteen Smokin’ Soul Senders which is a small part of a larger two CD set pictured above. If you poke around on the Louisiana Music Factory’s website, which is perhaps the most unhelpful, rudimentary music store website in the entire internet galaxy, you’ll find that and almost everything of Quezergue’s that’s in print.

Though Bartholomew and Parker continue to play sporadically, Smiley Lewis, Earl King, Tommy Ridgley and so many of the pioneers of New Orleans jazz and R&B have died, many since Katrina, that the old guard is nearly gone. Quezergue was the unknown giant of that scene, one of the most vital ever heard in the history of American music.

So many classic tracks that featured Wardell Quezergue's work.