| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Listening #148 Page 2

Having said that: When the choice existed, those same artists and producers often pointed to mono as the sound in which they wanted their music to be clothed. Even now, audio enthusiasts and record collectors praise the same qualities that appealed to the artists of the day: Mono LPs tend to offer considerably more substance and impact—more sonic flesh and blood—than their stereo counterparts, which can sound wan by comparison.

And to wring from today's mono reissues those selfsame qualities, it does, in fact, help to have a mono cartridge in your analog arsenal. The primary reason: A mono record groove has only horizontal modulations, and is designed to move a stylus only in that plane. Thus, a true mono cartridge outputs a signal only in response to horizontal stylus movement and, one hopes, is unresponsive to vertical stylus movement—the likes of which can result from mastering and pressing imperfections, or from the pinching effect caused by narrowing of the groove during high-frequency passages. Everything that's good and holy about mono playback is diluted by the addition to the lateral signal of nonlateral ephemera.

For that and a few other very good reasons—which I'll get to in a moment—a mono cartridge will always outperform a stereo cartridge at extracting from a mono record the more musically convincing sound. That said, there's no sense getting your hopes up if your current system isn't amenable to such changes. First and foremost, if you have but one turntable and tonearm, and if neither the headshell nor the armtube of the latter can be easily removed and exchanged, an auxiliary phono cartridge is impractical: Though it pains me to say it, unless you're willing to reinstall and realign your cartridge every time you want to switch from stereo to mono or back again—something even I am not willing to do!—there's really no sense in buying a mono pickup. Better you should save for an affordable auxiliary record player that can be dedicated to your single-channel purposes—or plan to upgrade, if possible, to an appropriate tonearm.

Wide load

A different and altogether trickier consideration awaits the budding monophile: The grooves of most contemporary mono reissues are not always the same size or shape as the grooves of the majority of original-issue mono LPs. In the words of the protagonist of a popular children's television series: "Ruh-Roh."

According to the International Electrotechnical Commission's (IEC) first-edition IEC-98 bulletin of 1958, the standard for the earliest mono LPs was a minimum groove width of 55µm, with a bottom radius of 7.5µm (anecdotal evidence suggests that the latter was sometimes larger). By 1963, in a bulletin devoted primarily to specs for the then-newish stereo LP, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) maintained the recommendation for a groove width of 55µm for mono, 25µm wide for stereo, and a bottom radius of 5µm for both. Just a year after that, the IEC renewed its standards to recommend groove widths of 55µm for mono grooves and 25µm for stereo, this time with a bottom radius of 4µm for both.

So it would seem that, throughout at least 1964, record-mastering engineers were cutting differently sized grooves for mono and stereo records—and, at the same time, that mono cutterheads and cutting styli were keeping pace with their stereo counterparts in terms of size and shape. (The cutterhead and its stylus determine the bottom radius of the groove cut into a lacquer, while the width of the groove can be determined by both the cutterhead and the cutting lathe, especially inasmuch as the latter gives the mastering engineer control over the vertical position of the cutterhead relative to the lacquer.)

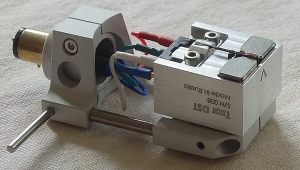

An original Ortofon mono cutterhead, with ruby cutting stylus in place, photographed at the Electric Recording Company studios, in London. (Photo: Art Dudley)

Technical standards are one thing, reality quite another—especially in an industry in which the number of units sold counts for everything, and where engineers lack faith in the consumer's ability to give a statistically significant number of fucks. According to veteran mastering engineer Steve Hoffman, the grooves of mono records from even the format's glory days did not always adhere to industry standards: "Capitol in 1960 had lathes from 1949 commingled with later models still in use—different stylus shapes, cutting amps, etc., going back to 1949. Some Capitol LPs of that era had one side cut with a modern 1960 stylus, [while] the B side was a repress from a 1953 stylus: totally different spec. All the record companies did this. . . . I've looked at many old mono LPs down through the years, and to my surprise found that many of those cut in the '60s were done on stereo lathes, just playing back a mono tape on a stereo machine. Especially after 1964."

To further tangle the tale: Just as most LP-reissue companies seem bashful about whether their records are mastered using a digital "preview" system—as opposed to an all-analog tape-head preview, which is to be preferred, as it avoids an unnecessary digitization—so, too, have they been less than forthright in describing the gear they use to cut mono lacquers. As of today, the Electric Recording Company is the only firm that I know uses a mono cutterhead: I've held it in my hand. I believe that at least some of the mono reissues from the late, lamented Classic Records were also made using a true mono cutterhead—and there may indeed be more. Any such mastering companies or engineers reading this are encouraged to please let me know. Better still: Please label your products more clearly!

More than a few of today's mastering engineers create mono lacquers by using a mono recording to drive a stereo cutterhead, sometimes with the lathe set for a deeper, wider groove than might otherwise be the case. It is my experience that, when challenged, those engineers describe their results as being no different from a mono groove made with a mono cutterhead. I admit that I have my doubts, born in part of my natural tendency toward skepticism whenever a technician declares that this or that subtle change makes no difference. But I am a listener, not an engineer, and my experience of the sounds of mono LPs is more cumulative than comparative; it is incumbent on me to keep an open mind.

In any event, the point is this: Unless the hobbyist intends to examine, under a microscope, every groove of every side of every record he or she sets out to play (apologies for putting so unfortunate an idea in the heads of some sensitive readers), there is simply no way of knowing, for sure, what size of stylus to use with what record. Sorry!

That said, I can offer a few general guidelines:

• If you want to enjoy some of the current crop of mono reissues, don't feel obliged to buy a mono cartridge right away. Your stereo cartridge won't hurt them, and those records will come out sounding pretty good.

• But if you persist in playing contemporary mono discs with a stereo cartridge and are underwhelmed, don't blame mono.

• If you want to enjoy only older mono LPs—say, those made before the mid-1960s, give or take a few years—then do consider a true mono cartridge, preferably with a spherical stylus with a radius no smaller than 15µm, and preferably used with an appropriate step-up transformer. Absent such gear, you simply won't hear what's so great about those records.

• The above applies also to those companies whose records are mastered using a true mono cutterhead—again, as opposed to a more modern stereo head summed for mono. At this time, the Electric Recording Company remains the only such company of which I'm aware—but, as suggested above, this space is open to anyone who writes in with a correction and a photo of their mono cutterhead.

• If and when you do buy a true mono cartridge, don't ever use it to play a stereo record of any era: You will damage the record's groove—and, as even the laziest engineer will acknowledge, that damage does make a difference.

• The use of a 25µm-radius stylus to play a contemporary mono record mastered with a modern stereo cutter head may not result in damage to the groove, but that's a chance I would not care to take. If your mono diet is to be split between old and new records, and if your budget allows for only one mono cartridge, choose one with a spherical stylus that has a radius of 15–18µm. My favorite candidates include the superb range of true mono cartridges from Miyajima Labs.

- Log in or register to post comments