| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Talent shows, even when it challenges you preconceptions. The worst thing you can tell an artist is that they're boring. Whatever your opinion - for honest musical reasons, rather than it's simply not your tribe's music - this music is not boring. It dares you to love it or hate it. And that, is about the finest thing an artist can do. (Incidentally, if you've ever read or seen interviews with great musicians, from any genre, they freely admit influences from and admiration for surprisingly disparate artists.)

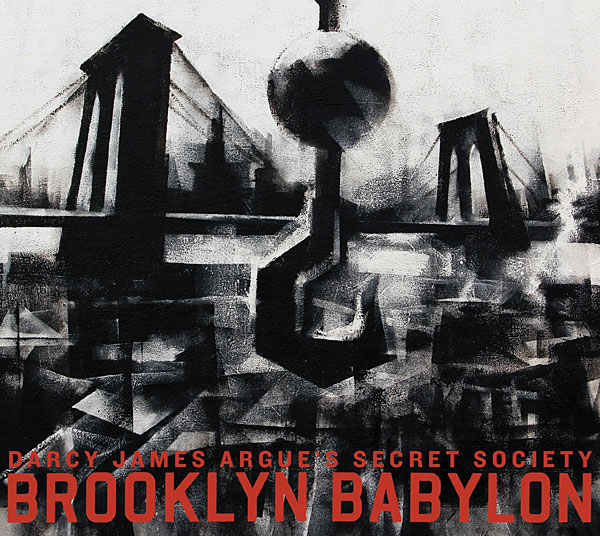

I started to list the influences I heard. I gave up; the list is too long. It's quite a feat to pull off a new hybrid without resorting to pastiche. Although it may not seem like a compliment, my initial reaction was that it's like movie music. But, music for a SERIOUS movie; one that invades your dreams that night and that you're still thinking about next day.