| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

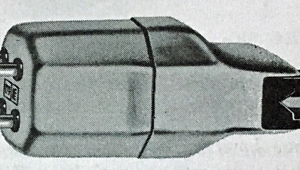

Koetsu Urushi MC phono cartridge

What makes a phono cartridge worth $3500 or $4000? Pride of ownership? Snob appeal? Sound? Tracking ability? Exotic materials? Styling? Labor cost for skilled artisans? Special ether? Cool wooden box? All of the above?

Can you really get your money's worth from cartridges that cost more than non-Stereophile readers spend on an entire stereo system? From ones that cost twice as much? They're out there. Is it worth having to handle something so pricey you have an anxiety attack every time you want to play a record?

Unfortunately, yes—assuming the rest of your system, especially your analog front-end, is capable of resolving what today's best cartridges can deliver. Do they do things the good $1000 and $2000 cartridges don't? In my experience, yes. Nonetheless, once past the $2000 price point, the curve of diminishing returns begins to flatten rather dramatically, and the differences become more subtle. They're still significant, but...subtle.

When you're spending $3500 or four grand on a phono cartridge, you have a right to expect a high degree of sonic accuracy. These days, if you find one expensive, high-performance cartridge that sounds radically different tonally from the rest, my experience is that it is either highly colored or defective.

If you're fortunate enough to hear a number of top performers under controlled conditions, you'll find that they all achieve a certain level of sonic performance, yet they all sound different in subtle but musically significant ways. In making your choice, you're going to have to examine those differences and blow them way out of proportion—which is what I had to do to review these two contenders, both of which make glorious-sounding music.

Cartridges are often compared to loudspeakers because both are transducers—they turn one form of energy into another. And while speakers and cartridges are the least accurate links in the audio chain, loudspeaker systems are far more complex and must interact with both the amplifier and the wildly variable room acoustic. Cartridges certainly have some tricky interfaces—record grooves, tonearms, phono-stage loads—but today's high-tech cartridge motors are far more accurate and predictable transducers than those used in the past.

All of the high-priced cartridges I've auditioned and reviewed over the past four or five years share certain characteristics that distinguish them from budget models. They all overcome the "edge" and grain structures lesser cartridges tend to impose on the music, but without softening or obscuring transient information and inner detail. (But if you're used to "edgy" performance, these sophisticated cartridges may sound "soft" at first.) In fact, as you'd expect and demand for your money, they resolve transients better and reveal more low-level detail, both spatially and musically, while avoiding the bright/hard or soft/warm tendencies of lesser designs. Overall distortion is much lower as well.

All premium cartridges, to differing degrees, have fewer frequency-response aberrations. They reproduce the frequency extremes with the same authority as they do the midband, and come closer to the ideal "flat" wideband response. But, like loudspeakers, all cartridges have some defining frequency-based character. Some of these characters are accidental; some, I suspect, are purposely "tuned in."

The expensive cartridges I've auditioned are built more carefully than massmarket models, both in terms of the quality and perfection of the parts used and in the way they're put together. This helps them achieve a better geometric relationship with the record groove. The result is superior separation, which creates wider, better-defined, and more accurate soundstages, more focused images, and better front-to-back image specificity.

When you spend $3000 or more on a phono cartridge, you should hear an immediate sense of ease, refinement, and liquidity, especially in the midband; a feeling of authority and control over the music; a complete freedom from "electronica" and artificiality. The better cartridges manage to untangle previously impenetrable webs of complex musical information without spotlighting or highlighting anything revealed. You sense that though a hundred events might be occurring simultaneously on the soundstage, you can hear each one individually. You can tune in and out of musical conversations much the way you can between people in a crowded room. And none of the images within the soundstage should appear to come anywhere near the confines of the drivers or cabinets.

Large-scale dynamic events like orchestral crescendos should strike your ears with a fast, violent impulse—uncompressed and completely controlled. And they should recede without a trace, leaving just the echoes ricocheting off the hall walls, clearly defined in a much different space. Low-level dynamic events—frequently occurring simultaneously with the large ones—should be portrayed with equal impulse clarity and detail, but in proper proportion.

Air, space, rich harmonic overtones, explosive dynamics, transparency, woody wood, metallic metal, fleshy flesh, a thousand colors, and a rich, seemingly limitless sonic bouquet—all, impossibly, painted by a stupid little diamond fleck motoring along a black vinyl highway. That's the goal. That's what's possible—performance I've yet to hear equaled by any CD player.

We like to think we get these things with $295 cartridges, and to some degree we do, but if you've heard either of these cartridges or any top performer, you've most likely heard and appreciated the difference made by superior materials, sophisticated design, precise construction, special ether, a cool wooden box, sleek styling, and snob appeal.

A different world

The original Koetsu Rosewood, introduced to America back in the late 1970s at the outrageous price of $800, was probably the first cartridge capable of achieving the performance I've just described. It immediately and convincingly bettered, in most ways, any other cartridge out there—particularly in terms of low distortion, harmonic richness and complexity, and stable, three-dimensional imaging. The original Koetsu laid bare the inanity of multimiked recordings like no cartridge before it.

I'll never forget the first time I heard one. Even though the record was The Cars' Candy-O—hardly an audiophile extravaganza—the presentation was so far superior to anything I'd heard that I had to have that cartridge. But I couldn't afford it. Instead, I visited the dealer incessantly to spin discs. (Fortunately, he had the time and we shared the same musical taste.)

Koetsu's distribution in America has been spotty; only recently have the cartridges reappeared on these shores, distributed by Musical Surroundings. The line runs from the Standard (Red) at $2500 up to the $7500 Onyx Platinum. The Urushi is second from the bottom at $4000—still a breathtaking amount.

I chose the Urushi because I had an opportunity to audition Bob Reina's "vintage" Urushi when he went tonearm shopping in my listening room. (He opted for the Immedia RPM-2 over the Graham 2.0, and the standard and 12" VPI JMW Memorial arms.) That original Urushi was built by the legendary Yoshiaki Sugano, now in his 90s. I wanted to hear if the "new" Urushi sounded as magical as Bob's original (he owns two—one for safekeeping). And yes—while Bob and a friend waited and listened, I performed, on the spot, meticulous cartridge setups on all arms.

- Log in or register to post comments