| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Wilson Audio WATT/Puppy System 5 loudspeaker Vowelling-In

Sidebar 2: David Wilson on "Vowelling-In" a Loudspeaker

Footnote 1: Could this be where he got the nickname "Mark"?

First of all, you have to realize that the boundaries are the enemy: they reflect sound, and most dynamic speakers are not designed to compensate for these reflected sounds. Of course, by definition, all rooms have boundaries. There are two ways to approach the problem of boundary interaction: one is to alter the boundary itself—make it so absorptive that it has no reflective quality. Or, you could make it so randomly diffusive that it breaks up the comb-filter effect and the standing waves. The approach that I use, however, is based on my observation that most end-users don't want to turn their listening rooms into anechoic chambers or studio environments. They want to incorporate fine audio equipment into their homes so they can enjoy music—it's that simple.

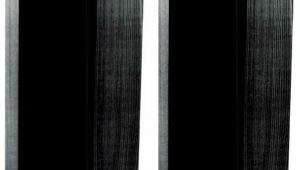

If you can't alter the boundary, you have to alter the speaker's relationship to that boundary. Now you don't really have any latitude in changing the speaker's relationship to the floor; that's essentially designed into the architecture of the speaker—the same is true of its relationship to the ceiling, obviously. The boundary behind the listener—the far wall—is so far away from the speaker that it doesn't have a primary influence on the response of the speaker. So we concentrate on the speaker's position relative to the walls behind it and to its sides.

You have to deal with those boundaries separately because they interact with the speaker in different ways. First we get a general reading of the room with voice. We find a "zone of neutrality" by speaking while we walk into the room, starting at the wall behind us. We know that a boundary will interact with a sound-source in predictable ways, so if you stand near a boundary and speak, you can hear it interact with your voice. As you slowly move away from that boundary, still speaking, you can hear that interaction change. Finally, you reach a point—somewhere out into the room—where there is very little perceived interaction. We mark that point with tape.

Walking farther into the room, you find that for a distance of a few feet, there is little change in the voice. Eventually, you get far enough away from the wall behind you—and close enough to the wall in front of you—that your voice takes on an echoey quality. We mark that point with tape as well. Using that marked area as a reference, we go through the same procedure from the side wall, again marking where the interactions change—we call the area bounded by our tape markings the "zone of neutrality," and the rest of the process consists of determining exactly where within it the speakers should be placed. [At this point in the procedure Mark Goldman lays down two tape axes, which he then marks in ½" increments so that he can precisely replicate any position within them for the fine-tuning stage.—WP (footnote 1)]

First, we adjust for the wall behind the speaker. Differences here of as little as an inch make a great impact on the bass-response of the system and the soundstaging. As the speakers are moved closer to that rear wall, they get more low-frequency reinforcement—sometimes actually becoming boomy in the upper bass—and the soundstage narrows. Pull the speakers toward the listener, and the soundstage gets wider while the deep bass loses reinforcement. You have to use your judgment, but as you become accustomed to this procedure, incremental changes produce predictable and recognizable changes in the sound.

We then adjust the speakers' relationship to the side walls without changing the distance we've established for the rear wall. We do this one speaker at a time, disconnecting the other one—using Ragtime Razzmatazz, a ragtime piano recording I made back in 1980. In establishing the purest harmonic structure, differences of as little as a quarter of an inch affect the purity of the sound. I call this "voweling" because I listen for the tones to change from "aaa" to "eee" or "ooo."

There are many methods of establishing speaker placement. In one approach you use a mirror to look at the speaker's reflection on the wall—which primarily works in the bass. A cable company recommends a method based on ratios, which has a great deal of validity if your room happens to be a rectangle. Even then, it works best in the lowest three octaves. But few setup methods address the midrange harmonic structure the way ours does. I'm not saying that our system's effective with dipoles, because they interact with the room in a different way, but for our speakers, or Thiels, or the other dynamic speakers I've had experience with, this really works well.—David A. Wilson

Footnote 1: Could this be where he got the nickname "Mark"?

- Log in or register to post comments