| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Music in the Round #46 Page 2

Next, I compared the DX-5's HDMI A/V Output with its own HDMI Audio Output. Instrumental to this task was A Virtuoso Faceoff, which includes pieces by Biber and Muffat performed by Petri Tapio Mattson (baroque violin), Eero Palviainen (archlute), and Markku Mäkinen (organ), recorded in the very warm, ripe acoustic of the Church of St. Lawrence in Janakkala, Finland (SACD/CD, Alba ABCD 311). Indeed, it did sound warm and ripe through both the DX-5's HDMI A/V output and the Oppo. Through the Ayre's HDMI Audio output, there was a decided difference in clarity and transparency that extended throughout the audioband. The Ayre's HDMI Audio output preserved the rich sound, but offered much greater distinction between the instruments—including the organ—and the ambience of the space. Switching to the Sony, I found that while it duplicated some of that experience, with greater treble clarity than provided by the Oppo, it failed to extend that clarity into the midbass and bass. As a result, the organ had too much reverberation, which somehow the Ayre managed to properly balance.

Footnote 2: McIntosh Laboratory, 2 Chambers Street, Binghamton, NY 13903-2699. Tel: (800) 538-6576, (607) 723-3512. Fax: (607) 724-0549. Web: www.mcintoshlabs.com.

The ability to distinguish the instruments' direct sounds from the sounds reflected by the venue's boundaries has always been, for me, the hallmark of true transparency, as it is the basis of the human ear/brain system's ability to direct the mind's attention to the sources of sounds in the ever-changing acoustical contexts of the real world. (I had a similar revelation when I first compared S/PDIF to I2S way back in 1996!) Now, and especially with multichannel's ability to envelop us in a performance space, the DX-5's HDMI Audio output permits us to listen as we would at the performance, focusing our attention on the performers while sharing the ambience with them. This isn't an obvious thing at first, and certainly not as striking as a change in frequency response or harmonic distortion, but once my brain locked on to this parameter, the difference between the Oppo's HDMI and the Ayre's Audio HDMI was impossible to ignore.

From there, I played a number of my favorite discs (see sidebar, "Recordings in the Round"), and found that almost all were refreshed by this newfound clarity. In some discs, with drier and/or synthetic acoustics, the improvement was not as explicit, but it still permitted me to play them at higher levels and take advantage of their dynamic range without the music smearing into the ambience.

You might suspect, reading this, that the Ayre was thinning out the sound. That this was not the case was demonstrated by the DTS-HD MA track of Tom Petty's Mojo (Blu-ray, Reprise 523977-BA2). Here, the Ayre's HDMI Audio output was, if anything, a bit less bright than the legacy A/V output, yet with more presence and bite. Moreover, the exquisite layering of instruments in John Neschling and the São Paulo Symphony's recording of Respighi's Pines of Rome, Fountains of Rome, and Feste Romane (SACD/CD, BIS SACD-1720) was superbly detailed, while the exquisite antiphonal brass remained comfortably within the same acoustic environment. The Ayre's tonal balance was neutral, but through it, transparency and dynamics were enhanced. Not one of the dozens of recordings I tried demonstrated otherwise.

The superior sound of the DX-5 was apparent with the Meridian 621/861, the Classé CT-SSP, and the McIntosh Labs MX150 A/V Control Center (see below), but not with the now-dated Integra DTC-9.8 pre-pro, which proved an unsuitable mate even through an analog connection. Was all this due to lower jitter via Ayre's HDMI? I don't know. What I do know is that I preferred the DX-5's HDMI Audio output to that of any other disc spinner so far. Is it worth the substantial price multiple over the stock Oppo BDP-83 ($499, no longer in production) or stock Oppo BDP-83SE ($899). That will depend on what you connect it to and what you listen for. But if you want to extract all the subtlety and detail from the best multichannel discs, Ayre Acoustics' DX-5 demands your consideration.

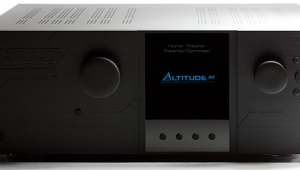

McIntosh Labs MX150 A/V Control Center

Another column, another pre-pro? Yeah, but this is a McIntosh (footnote 2). The Mac components I've used have taught me that along with their classically bold appearance come high performance and superb ergonomics—and these days, the latter is in shorter and shorter supply. On the one hand, designs like the Integra and Krell preamplifier-processors are covered with as many controls as will fit their front panels, matching the imposing arrays on their rear panels. On the other hand, the Classé and Meridian pre-pros are refreshingly clean, but require touchscreen menus and/or remote controls to do anything other than adjust the volume. Makers of two-channel preamplifiers and integrated amplifiers have somehow figured out how to provide just enough control options in unconfusing arrangements that welcome the touch of a human hand, and so have the designers of this sophisticated pre-pro. The McIntosh MX150 A/V Controller ($12,000) seems to invite you to use it.

Two things, on paper, clearly distinguish the MX150 from the other pre-pros I've reviewed in recent months. First is its ability to interact with and control other components, made by McIntosh and some other firms, through arrays of trigger and sensor inputs, IR and power control ports, and data inputs/outputs, as well as the more common Zone 2 A/V outputs, RS-232, Ethernet, and USB connectors. In addition, the MX150's rear panel has a port for a Compact Flash card, for the exclusive use of service personnel. I'll say nothing more about these, as I am a one-zone man. The other notable feature of the MX150 is the inclusion of the RoomPerfect room-correction system from Lyngdorf Audio, not widely available in the US until now. McIntosh also makes a standalone two-channel RoomPerfect EQ device, the MEN-220; in the MX150, RoomPerfect can be applied to all Zone 1 channels.

Connection of the MX150 is similar to that of any modern pre-pro with HDMI handling A/V input and video outputs. There are, of course, sufficient digital audio inputs (four coax, one AES/EBU, four optical), analog audio inputs (eight RCA, two XLR for stereo, one RCA multichannel), phono (MM only), and legacy video inputs to support almost any needs. There are 7.1-channel analog outputs with both RCA and XLR jacks, as well as two Aux outputs of each variety. The latter are low-pass-filtered outputs from the main L/R channels, and can be configured to support bi-amping of those channels, complete with proper crossover.

However, setup these days is not complete until one wades through a hierarchy of menus. McIntosh makes this easier by supplying large foldout charts to illustrate all the default connections, and settings and guides for customizing them. But because I used mostly HDMI sources, along with the phono stage and the multichannel analog inputs, there was very little to do except rename the chosen inputs to distinguish, say, Oppo, Sony, and Cable TV. About the only other thing I needed to do was tell the MX150 about my speakers: number, size, crossover frequency, and distance. This can be done with the friendly front-panel controls or with the remote control, though I was less nimble with the latter's many small and similar buttons. In addition, many of the labels on the remote are tiny. Surprisingly, although the remote is backlit, it illuminates only the buttons themselves, not their labels! I guess long familiarity might minimize that inconvenience.

There's a better way. Connect the MX150 to your home network, find the MX150's IP address from the menu, type it into your preferred Web browser, and up on your computer screen pops the Mac's complete control-system interface. I greatly preferred this version of the control system to remote or front-panel access. First, it's more comfortable to navigate the menus by mouse or touchpad while seated comfortably on the sofa. Second, since the menus are on the computer screen, the main system's audio and video are not obscured or preempted; you can hear and see the changes as you make them. This is the way to go.

The MX150 was a delight to use. The front-panel controls are clearly labeled, and include input and mode selection, volume, channel-level trim, and many other frequently used functions. The clearly illuminated information display is legible from 15' away, and can show much more than just source and volume. In addition, illuminated labels indicate the active input and output channels, whether the selected input channel is analog, digital, and/or HD, and whether or not RoomPerfect is engaged. Speaking of which . . .

RoomPerfect operates in a manner distinct from that of other room-correction programs. First, RP makes little effort to correct your speakers' on-axis frequency responses, based on the supposition that you picked them because you liked them. Instead, the software attempts to correct the system's in-room power response as well as the modal behavior in the low frequencies. To do this, the first reading—called the Focus measurement—is taken from the listening position, with the provided microphone aimed directly forward at the center speaker. Additional measurements are taken at random positions and mike orientations, the RP analysis system gathering more and more information about the soundfield in the room. An index of how much the system "knows" is displayed after each measurement. One is advised to measure until RP's "room knowledge" exceeds 90%. That took me just four measurements, and is in accordance with Lyngdorf's AES paper on room sampling (footnote 3). Three more measurements got me to 96% room knowledge.

Footnote 2: McIntosh Laboratory, 2 Chambers Street, Binghamton, NY 13903-2699. Tel: (800) 538-6576, (607) 723-3512. Fax: (607) 724-0549. Web: www.mcintoshlabs.com.

Footnote 3: Jan Abilgaard Pedersen, "Sampling the Energy in a 3D Sound Field," presented at the October 2007 AES Convention: www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=14319.

- Log in or register to post comments