| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Muse Model 150 monoblock power amplifier

The name Muse Electronics is probably unfamiliar to most audiophiles, requiring some background on the company. Muse is the hi-fi offshoot of a company called Sound Code Systems, a manufacturer of professional sound-reinforcement speaker cabinets and power amplifiers. Founded in 1980, SCS enjoyed some success with its line of MOSFET professional power amplifiers. In 1988, SCS's Michael Goddard and Kevin Halverson, both audiophiles and tube aficionados, redesigned their amplifier for the high-end hi-fi market.

The name Muse Electronics is probably unfamiliar to most audiophiles, requiring some background on the company. Muse is the hi-fi offshoot of a company called Sound Code Systems, a manufacturer of professional sound-reinforcement speaker cabinets and power amplifiers. Founded in 1980, SCS enjoyed some success with its line of MOSFET professional power amplifiers. In 1988, SCS's Michael Goddard and Kevin Halverson, both audiophiles and tube aficionados, redesigned their amplifier for the high-end hi-fi market.

The results are the Model One Hundred (a 100Wpc stereo power amplifier) and the Model One Hundred Fifty ($1900/pair), the 125W monoblock reviewed here. According to Michael Goddard, the primary design goal was to achieve a tube sound with the reliability and ruggedness of transistors. MartinLogan CLS speakers were used extensively during the design/listen/design cycle. As a result of their listening auditions and redesign, many of the changes have now been incorporated into their professional products.

The Model One Hundred Fifty (the 150 for short) is a sturdy-looking unit, as befits its lineage as a rugged professional product. The brushed-aluminum front panel is given a "bulletproof" appearance by the hex-bolts that hold the power transformer and heatsinks. These heatsinks flank either side of the amplifier and, along with its low profile, give the 150 a streamlined look. The chassis and top cover are very heavy and solid, adding to the impression of a sturdy build. The rear panel holds a gold-plated RCA jack, hefty power cord, AC line fuse, and binding posts for speaker connection. Overall, the look of the amplifier is subtle and understated.

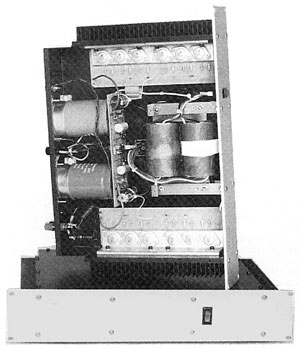

Under the hood, the 150 is extraordinarily simple. It has very few components, but these tend to be large and hefty. The 550VA power transformer consumes much of the interior space, and the two electrolytic filter caps (10,000µF each) are each about the size of a soda can. The driver board has very few components (all discrete), and appears well made. Polypropylene and polystyrene film caps were in evidence. The 150's output section is impressive. Using 12 MOSFET output devices on large heatsinks, one is given the impression of high current capability and stability into low-impedance loads. Indeed, Muse claims the amplifier is capable of delivering 70A peaks to the loudspeaker.

The front end is fully symmetrical from input to output. The differential pair, current source, class-A voltage gain stage, and emitter follower that drives the MOSFET gates are all mirrored from the positive to negative rails. This balanced circuitry makes converting the amplifier to balanced inputs simply a matter of changing the RCA input connector to an XLR. To ensure that the front end is isolated from any momentary power-supply voltage fluctuations, the power-supply rails are diode-decoupled before being fed to the 220µF front-end filter caps. Feedback is taken locally (at the MOSFET gates) instead of globally (at the MOSFET outputs) which, according to the designer, results in a "more liquid, tube-like midrange."

The Sound

I had just finished listening to a jazz recording I had engineered of a straight-ahead jazz group recorded live to DAT with tube mics through the Carver Silver Seven-t amplifiers when I hooked up the pair of Muse 150s. Even though they were not warmed up, I wanted to conduct an immediate comparison with the Carvers using the same recording. The difference was shocking. Where the music had been lackluster and uninvolving through the Carvers, it now jumped to life through the Muses. What was really interesting is how radically my involvement in the musical performance changed just by changing amplifiers.

Quite apart from things like smoothness, soundstaging, depth, etc. that I will discuss later, I had the impression I was listening to a different band! All the excitement and energy of the original session jumped out of the speakers. As they ate up the changes, the free-flowing intensity generated by these veteran jazz players was palpable. A flood of memory was jolted loose: I could visualize the musicians, where they stood and their reactions to each others' playing. It was impossible to keep my foot still. How could this be the same recording that did nothing for me minutes earlier? That changing a component in the reproduction chain could make such a difference in the feeling of a performance was surprising. And the Muse monoblocks were still cold.

After about an hour of warmup, I went back to listening to find out what these amplifiers really sounded like. I must admit that I had a bit of negative bias toward the Muse amplifiers, based on their sound-reinforcement heritage. If you've ever hooked up a PA amp in a hi-fi system, you will know what I mean. I was, however, encouraged by this experience with my jazz recording.

- Log in or register to post comments