| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Listening #142

". . . with faithfully replicated artwork."

Footnote 1: Soon after I bought my LP12, I bought and installed Linn's Cirkus upgrade, but liked it less than the original subchassis and bearing—to which I reverted.

That's how a press release, dated June 16 of this year, described the manner in which the next wave of Beatles LPs—mono releases claimed to be mastered direct from the original analog mixdown tapes, and not the 44.1kHz digital files that Apple Records and Universal Music Enterprises (which now owns EMI) considered good enough for their last wave of Beatles LPs—are being packaged for sale. Hope, as Emily Dickinson once observed, is that thing with the feathers. Which, as we all know, evolved from the dinosaurs.

Those new mono LPs, available as individual albums and as part of a lavish boxed set, should hit the shelves around the time you read this: Official release dates are September 8 for the UK, September 9 for the US. Only then will we learn if Apple and Universal have honored the group with LPs that not only sound like the UK originals—remarkably, this would be a first—but whose jackets use the right materials, the right laminations, and the right exposed-flap construction. Artwork that has been screened for offset printing or, at the very least, competently scanned, would also be nice.

By now, Apple and Universal might have learned a thing or two from the Electric Recording Company, a British reissuer of LPs that also enjoys access to EMI's trove of historic recordings—and yet bows to no other in sweating the small details, or in rejecting the attitude of "good enough" espoused by some engineers. As I described in the July 2013 "Listening," the ERC's extremes aren't limited to searching out and reconditioning playback and mastering gear appropriate to the era of the recordings they offer—including monophonic disc-cutter heads, to which a stereo head driven by a signal summed for mono simply does not bear comparison. They are known for resetting original LP liner notes in old-style lead type, searching out the right silk cord with which to bind the booklet for one of their releases, and spending considerable time and money to obtain the correct card stock for their packaging. Now the London-based company has taken on a challenge that combines vinyl, card stock, and lumber: a re-creation of a 1950s French classical-music album in a sleeve with a wooden edge.

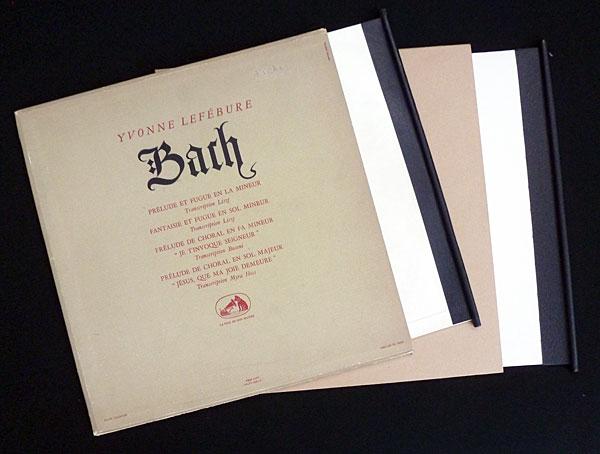

Dowel-spine jackets, though uncommon in the US—a few Everest and Angel titles of the 1950s are exceptions—were all the rage in France, especially from the label La voix de son maître (His Master's Voice, aka HMV France). And the Electric Recording Company has set out to reissue one of the rarest jewels in that label's crown: a J.S. Bach recital by pianist Yvonne Lefébure (FBLP 1079) that includes the Prelude and Fugue in A Minor and the Chorale in G ("Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring"), original copies of which routinely sell for four figures. (A Beethoven recital of Lefébure's, released as FBLP 1080, is even rarer.)

The original packaging was the sort in which the outer jacket and inner sleeve were of more or less equal substance, and were equally dependent on wood: a round dowel for the inner sleeve, apparently intended to give the owner a handle of sorts to grab when removing the record from its packaging; and a flat strip of wood at the edge of the outer jacket, to maintain the proper thickness and spacing overall. In US examples I've seen—including the Everest release of Sir Adrian Boult and the London Philharmonic playing Mahler's Symphony 1 (SDBR-3005)—an extra strip of cardboard takes the place of the wooden spacer, while the dowel at the edge of the inner sleeve is of square cross-section.

In preparing this LP, which is scheduled for release later in 2014, ERC says they spent months researching materials choices and construction techniques alone. The photo shows their finished prototype and an especially clean original, one atop the other; I leave it to you to guess which is which.

Borrowing something new

Contrary to a belief that has been expressed on at least one quaint old British website, I do not dislike the Linn LP12 turntable: I like it. I bought mine 26 years ago, brand new, from an especially dedicated Linn dealer. (For a short while that dealer even carried the Roksan line, just so they could use a hobbled Xerxes as a foil for their well-set-up LP12. Now that's dedication!) I still own my LP12, which has an afromosia plinth, a 60Hz motor, an internal Linn Basik "power supply" (actually a simple motor-phasing circuit), and a pre-Cirkus subchassis and platter bearing (footnote 1).

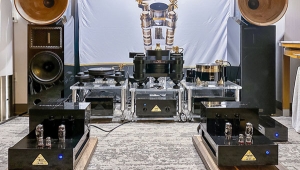

My Linn spent several months in our guest room, perched on a sofa next to a pile of old photographs and an unappealing cookie jar shaped like a bullfrog. (When I see a green, cold-blooded, fly-eating amphibian with an enormous double chin, I think: delicious home-baked treats.) But earlier this year, while attending High End 2014, in Munich, my Linnterest was rekindled by a silently displayed LP12 fitted with a sample of the new 9W2 tonearm ($3500) from the Bavarian firm Analog Manufaktur Germany. The AMG arm appeared both well made and sufficiently original to justify its existence—but without the excess of those designs in which every element is reimagined, possibly without need. The AMG tonearm looked right, and I looked forward to trying it on my couch-potato Linn.

When last the Linn graced my system, it supported an early-1990s sample of Rega Research's classic RB300 tonearm. Don't let the flattest flat-earther tell you otherwise: The sound of the combination of an LP12 and an RB300 is tuneful, rhythmic, organic, pleasantly chunky, and altogether excellent. In my experience, people who regard the late, lamented Naim Aro as the ultimate arm for the LP12 are often the same people who regard the RB300 as the next best, superior even to the nice but slightly clangy Linn Ittok. On the other hand, people for whom the LP12's ultimate mate is the Linn Ekos—a tonearm that I deeply admire and enjoy but don't quite love—tend not to get the RB300, as is their prerogative. In fairness, I should note that, in order to succeed on the LP12, the Rega arm requires some extra attention: Electrician's tape or something like it needs to be wrapped around the Rega's skinny-ass, hardwired signal cable at the point where it must be gripped tightly by the LP12's primitive P-clip. And, especially in locales with wide ranges of temperature and humidity (upstate New York and Fairbanks, Alaska, come to mind), one needs to retighten the RB300's big locking nut every now and then.

The latter was recently true of my own Linn-based player, which needed setup attention in other respects, as well. Not only were the three suspension springs misaligned with the long bolts running through their centers—surely a consequence of sitting for so long on a non-level surface—but, as I discovered when I removed the metal "strap" that extends from the turntable's frontside to its backside, the nuts that fasten the LP12's stainless-steel top plate to its nice old hardwood plinth had become noticeably loose (also caused by heterogeneous weather, I suppose). Those chores and the fine adjustments that followed were neither difficult nor mysterious—tuning the Linn's springs is a simple matter of getting all three corners of the leveled suspension to bounce at the same time and rate, itself a matter of "relaxing" the springs and keeping them from being fouled by their respective suspension bolts—and before long, records played on my combination of LP12, RB300, and Miyabi 47 phono pickup sounded very much like music.

The AMG arm arrived in June, and with the opportunity to hold it in my hands, I was no longer merely impressed: I was stunned. Our hobby has been blessed with some beautifully made tonearms, including the Aro and Ekos, as well as the Mission Mechanic, the Zeta, Sumiko's The Arm, and various iterations of the Ikeda. None surpasses the 9W2 in sheer build quality. The German arm's surprisingly small yet chunky bearing assembly, in particular, is so precisely made—and so obviously free from both friction and unwanted play—that it could impress even those who are indifferent to phonography.

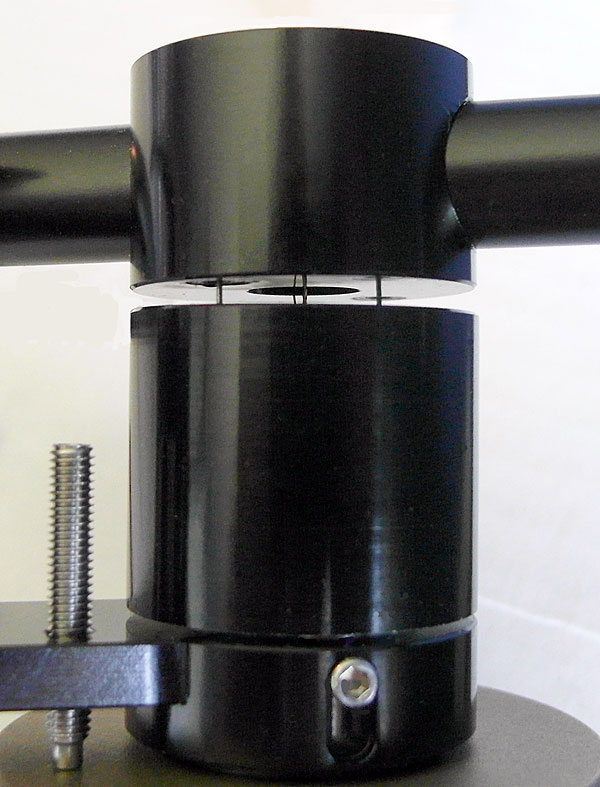

Fun without play

The design of the AMG 9W2's bearing is no less remarkable than its build quality. Although the horizontal bearing (footnote 2) is somewhat traditional—an axle of hardened tool steel configured as a needle/roller bearing—the vertical bearing, which appears to exhibit zero play whatsoever, is unique to audio: an upright pair of 0.4mm spring-steel wires that are perfectly straight when the tonearm tube is balanced, yet flex in tandem and yield to the armtube's mass when the counterweight is moved closer to the twin fulcrums. Those fulcrums, by the way, are arranged as two points on a line precisely parallel to the arm's offset angle (24.07°), so that azimuth doesn't change as the cartridge moves up or down.

Footnote 1: Soon after I bought my LP12, I bought and installed Linn's Cirkus upgrade, but liked it less than the original subchassis and bearing—to which I reverted.

Footnote 2: By which I mean the bearing that facilitates the tonearm's horizontal movement—a mildly confusing distinction, given that a traditional tonearm's horizontal bearing is aligned vertically, and its vertical bearing is aligned horizontally.

- Log in or register to post comments