| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

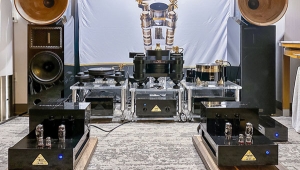

"When the comparison ended, all of us agreed that one phono stage pulled out our feelings and directed our attention to the art being performed, the other didn't. The other lent itself to logical analysis—and by that standard did very well."

What's interesting is that this reaction seemed to be unanimous, among the group. In my experience, I have found that one person's "analytical" is another person's "analog / musical". My first "big boy" system consisted of speakers that I am guessing were built by your host, and fueled by gear distributed/dealt by others in the circle of trust, but it didn't quite do it for me. Which is fine! It's only audio, and there are a lot of choices out there.