| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Convergent Audio Technology SL1 Renaissance preamplifier

"Are You a Sharpener or a Leveler?" was the title of my "As We See It" in the February 2009 issue. The terms sharpening and leveling come from work in the field of perception by the early Gestalt psychologists, sharpening referring to the exaggeration of perceived differences, leveling to the minimization of those differences.

In discussing how these terms apply to high-performance audio, I suggested that if audio designers are to succeed in this highly competitive field, they must be sharpeners: they must pay attention to differences that may be very small but that, in the aggregate, could produce a significant improvement in sound quality. I've encountered a good many audio designers whom I would describe as sharpeners, but perhaps none more than Ken Stevens, of Convergent Audio Technology (CAT).

A case in point: A few weeks after I'd received the review sample of CAT's SL1 Renaissance preamplifier, Stevens called to tell me that, because of an error by their parts supplier, some capacitors in the phono section of a few Renaissance units weren't exactly as specified. (It has since been determined that only three samples of the Renaissance were affected, my review sample being No.3.) The difference wasn't something obvious, such as capacitor value, but the metal used in the capacitor lead wire. That wire was supposed to be made of copper, but for some of the capacitors copper-clad steel was used. Stevens admitted that the sonic difference produced by the lead wire was small, and would not show up in any conventional measurement of the Renaissance's performance, but it was one that he could hear in his own high-resolution system.

He said that only a practiced eye could tell by looking at the capacitor which kind of lead wire it had, and he wanted to ensure that the review sample represented current production. Stevens offered to visit me in Toronto (the CAT factory is in Rush, New York, near Rochester, about a three-hour drive from my house) and, if necessary, replace the affected capacitors. That was fine with me—the visit would also allow him to confirm that the Renaissance was working as expected in my system. (By that time I'd already listened briefly to the phono section, and couldn't tell that there was anything amiss.)

And so it came to pass that, a few days later, Ken Stevens showed up. After a bit of listening to CDs, which satisfied him that the Renaissance was working well in my system, he removed the preamp's top panel and pronounced that while one channel of the phono section had the proper capacitor, the other didn't. He proceeded to unsolder the capacitor with the wrong lead wire and install the correct one. However . . .

One of the important design features of all CAT products is vibration control. To help damp any vibration of the circuit board, the larger capacitors are glued to the board using a special adhesive. Stevens had not brought a tube of this adhesive with him. He could have left the replacement capacitor unglued—again, none of the preamp's measurable attributes would be affected—but that would not do. So we made a trip to a nearby Home Depot, where Stevens spent considerable time determining which of the adhesives they had in stock had the right characteristics: not too hard when dried, but not too soft, either. Finally, he found an adhesive that, while not the same brand used by the CAT factory, had properties sufficiently similar. We drove home, and he completed the installation of the new capacitor.

Now, that's what I call a sharpener.

Renaissance SL1

The original CAT SL1 was introduced in 1985, and quickly established a reputation of being one of the best—if not the best—preamplifiers on the market. I bought a later edition, the SL1 Signature, in 1993, and although I've since heard some other excellent preamps, the SL1 has remained, in various incarnations, my reference preamp.

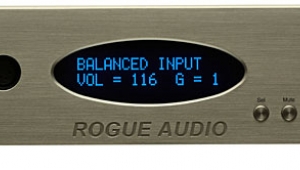

The basic design of the SL1 Renaissance ($9995) is pretty much the same as that of the original SL1: It's still a two-channel tube amplifier with volume and balance control, phono stage (a version without phono stage costs $7950), no remote control, single-ended rather than balanced inputs and outputs, and a separate power supply connected by a thick, hardwired cable. I've always found this cable a pain to deal with, and during Stevens' visit I asked if he might consider using a detachable cable.

He told me that although hardwiring the cable has some audible benefits, his original reason for this design was a practical one: reliability. When designing the original SL1, he'd wanted to ensure that it not only sounded great but was reliable as well. He asked a major dealer for Audio Research if there was any one problem with ARC's SP-10—widely considered the top preamp at that time—that regularly required warranty service from the factory, and the dealer had an answer: the connections between the detachable cable connecting the preamp to its power supply. Stevens decided that this was one problem his preamp wasn't going to have; the sonic benefit was something of a bonus.

Over the years, there have been numerous changes in the SL1, some of which led to changes in its name: Reference, Reference Mk.II, Signature, Signature Mk.II, etc. The last revision resulted in the SL1 Ultimate, which I reviewed in August 1999. At that time, I'd kidded Stevens about the Ultimate designation: If you say that a product is the ultimate, what do you call its successor? Is it possible to have something better than the ultimate? Does, say, "Ultimate Mk.II" even make sense? It would be like a football coach saying "The players gave 110%."

- Log in or register to post comments