| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

All the music reviewed on this site is so old, so much in the past.

"Oh yeah, absolutely. Sound has always been important to me, but I've never known very much. I had a great conversation with Glyn Johns once, and I was saying, 'I don't really know about the bass. I don't know how to get, or even what, a great bass sound is.' And he says, 'You know.' I said, 'No, I really don't know,' and he says, 'You know—of course you know.' And that's all he would say. He was wonderfully, eloquently brief.

"You have to work on it, make it sound good—there are all kinds of tricks, but if you're waiting for someone to walk in and hand it to you on a silver platter . . . and, actually, every now and then that does happen, where someone comes in and does something to your song that is amazing, that you could have never guessed, and you live for that pleasure of having someone elevate it way beyond what you were shooting for. But in most cases, I really don't think anything can take the place of you rolling up your sleeves and going about getting everything you want to have happen happen.

"In the case of Late for the Sky, and also with the new record, working with an engineer who is willing to go through the learning curve of discovering what you can get from the songs is more important to me than passing it to some master who's heralded by all to have his own sound but who doesn't have the patience, or the chemistry, that allows you to interact. These masters I am referring to, like Bob Clearmountain and Ed Cherney, I probably could get it, I probably could work with them in a longer frame. What I couldn't do is work with them for a year, going through all the nonsense I do to get the song where I want it to be. They have other projects. So working with my engineer, Paul Dieter, [on Standing in the Breach], when we finally decided, 'Hell, let's mix this ourselves!'—it felt great, it felt fresh, the way a lot of great records have been made by people who were on hand. Like when Jon Landau worked on The Pretender. He had a really great reference system set up in his hotel room, and he'd go back and he'd listen intently. With Standing in the Breach, I had to have the confidence to get it the way I wanted it—because I was listening, I was driving, and I decided to take on that responsibility."

As for his back catalog, Browne said that there are some records whose sound he's less than pleased with.

"I've thought about going back and remixing the last record, Time the Conqueror, which was mixed by Elliot Scheiner. Elliot is a great engineer, one of my favorites, I love the sound of his records. But there, I couldn't interact with him in the mix because I was busy writing the last verses to songs in the next room, and I was just going to the master and saying, 'Make this finished.' So it's my fault. But I have to say that a lot of what he did was not what I was hearing, all through the making of the record. It was that experience, really, of thinking, like, 'Hmmm, what he did with the drums . . . I like the way we played it.' There was something about the inner compression of the drums.

"The biggest problem I had with that record is there was one singer that I couldn't get him to turn up loud enough. The way he wound up hearing the girls that sing with me, it just wasn't what we had. But then maybe it's my hearing. Maybe that frequency is just not there in my ears and it was plenty loud. That actually happened, working really late hours one night on this record, when I said, 'Can't we just turn that voice up?' And Paul [Dieter] was saying, 'It's really loud already—do you really want me to?' The next day, after a night's sleep, I listened to it and he was right—it just wasn't there the night before."

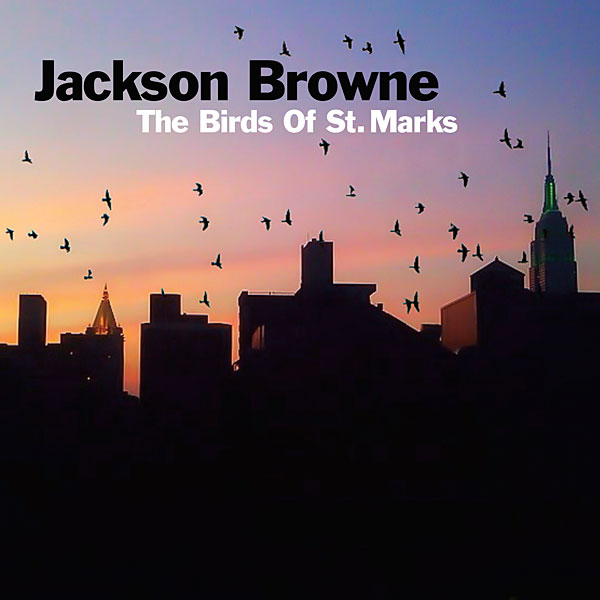

Standing in the Breach contains perhaps Browne's most inspired wordsmithery since his early days on Elektra. Those lyrics are joined to a number of solid melodies, as in: a fabulous reimagining of Woody Guthrie lyrics as "You Know the Night"; "Leaving Winslow," which namechecks the Arizona burg famously mentioned in "Take It Easy" (which, on the current tour, is often the encore); and "Yeah Yeah," which sounds like an outtake from one of those glorious early Browne records. One, "The Birds of St. Marks," is a previously unrecorded song from even earlier: 1967, when Browne had a New York City romance with Nico (who died in 1988). It's the new record's most unique-sounding track, thanks to the unmistakable shimmer of Greg Leisz's 12-string electric guitar.

"I wrote this song for Nico, and you would probably never guess, but she was a big fan of the Byrds. She particularly liked 'Eight Miles High,' and thought that the guitar playing was really avant-garde—that the 12-string part . . . was really the Byrds being influenced by Coltrane. They were very searching. That was pre–country-music Byrds. They had Hugh Masekela—they had a South African trumpet player on 'So You Want to Be a Rock 'N' Roll Star.' They were very adventurous.

One difference between Standing in the Breach and many Jackson Browne albums is a distinct lack of preachiness. "You wanna offer people something of use, of value. It's hard enough to talk about something, like how compromised the ocean is. You want to direct people to the fight, not to remind them of how much we've lost. There's a great quote—Carolyn Forché, in one of her poems, says, 'It is/ not your right to feel powerless / better people than you are powerless.'

"I think of all the advantages we have, not just economically. There's a lot of good luck, you know, in the United States; there's a lot of coming together. We have these incredible natural resources, and these incredible diverse cultures interacting. It's an open society, there's a lot of good stuff here. And there's quite a bit left that we haven't really done. The destruction of the environment, and destroying so much of what the United States was able to make happen in the last century, is the way we do business. Unregulated capitalism is destroying what regulated capitalism gave us. And it's all in the name of undiminished wealth for a few.

"This is the fight. This is the same fight that's going to be happening in every other country in the world, too. Anything you can do to get people to think in terms of the possibilities of what they might be able to contribute or might be able to do would be a help. Despair has never been my aim. I've always been willing to talk about sorrow, or even express how difficult a situation might be—but as long as you leave some way of moving forward, of getting to the fight."

"PLAY WHATEVER YOU WANT!" comes a final shriek at the Beacon. The crowd applauds.

Browne leans forward to the mike. Another big smile.

"Maybe we should do what they tell us to do . . . ?"

All the music reviewed on this site is so old, so much in the past.

So go to another site.

The meaning of this obviously escapes you. Attacking the messenger, me, won't change the facts that, firstly, the demographic for this magazine is very old, older than mean middle age, and, secondly, the demographic for high-end is also just as old.

amen. or he could actually read the magazine/website and see all the newer music that's on there. but then he couldn't be as snarky and self-righteous.

The parade has passed high-end by. This is in part generational, in part technological.

Simply put, quantity has trumped quality. More, cheaper and easier mass distribution of music of inferior audio quality prevails. Audio quality is not even a secondary consideration compared to means of access. Audio quality is no longer a primary or important commodity.

Interconnectivity of electronic devices is much more a priority than excellence of sound quality. The inherent, unalterable nature of digitized musical signal is homogenized and mediocre. Raising bit rates and sampling frequencies is of importance to only a marginal, exceedingly small and specialized market. Every indication is that these trends are only growing.

The music itself has qualitatively changed, becoming more and more artificial, more and more synthetic, as befits the means of production, reproduction and distribution.

The large majority of audiences at classical concerts is gray-haired. It has been said, not without justification, that jazz reached a state of arrested development after John Coltrane.

Adjusted for inflation, the cost of audiophile gear has skyrocketed in the last, say, 20-25 years, due to ever decreasing sales volumes and a shrinking market. Compare this to computers, in their various forms, which keep getting rapidly cheaper and cheaper due to higher and higher sales volumes. The higher the sales volume, of course, the less the profit margin has to be per unit, and vice versa.

Easily more than half the recordings reviewed in Stereophile have a demographic of well over 50, if not 55-60. The parade has passed.

PS. Snuck into a Jackson Brown concert on my way home from the library at UCSB one night. Left after 10 minutes. "Brown" describes his music perfectly, i.e., drab, i.e., David Geffen, ultra commercial, supposedly noncommercial LA pop. Actually kinda like These Days and Doctor My Eyes, but little else. There was so much other, better music then (e.g., Weather Report, who also performed at UCSB).

Sneak into a Justin Bieber concert. You'll be happier.