| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

On The Road Again: Three European Jazz Festivals Page 2

Baas was effectively an artist-in-residence: He appeared at least seven times. Diodati and Baas played together once, in an ad hoc band with American bassist Joe Rehmer and Austrian drummer Lukas König. They performed in Batzen Sudwerk, a cramped, dark, beery cellar in Bolzano, the antithesis of a Dolomite meadow. They instantly created a group identity, two starkly different guitars commingling in glittering curtains of sound. One of Baas's best concerts was a duo performance with another guitarist, Ella Zirina, who was his student at the Amsterdam Conservatory. Their lyrical, ornate, heartfelt versions of "A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing" and "I Loves You Porgy" were long but ended too soon.

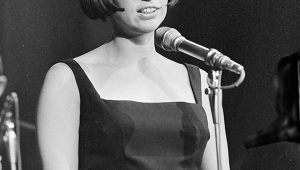

Sanem Kalfa, Fuensanta Méndez, Südtirol Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

Perhaps because of the absence of big names and egos, and the audience's close proximity to the musicians, and the beauty of the surroundings, there is a sweetness to this festival like no other in my experience. And Südtirol always contains some revelations. One day, I took a twisting bus ride up a green mountain to a farm restaurant and heard a duo I didn't know: cellist/ vocalist Sanem Kalfa, from Turkey, and bassist/vocalist Fuensanta Méndez, from Mexico. They blew me away. They cast a spell. Their exquisitely pure soprano voices floated free in the crowded room. People seek out music because it can release you from the bondage of self.

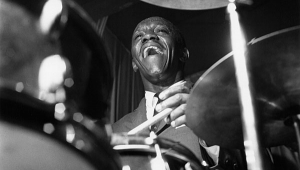

Nick Jurd, Soweto Kinch, Jason Brown, Suüdtirol Jazz Festival. Photo by Florian Dariz.

Another surprise was a concert by Soweto Kinch of the UK. The program listed the location as "secret." It turned out to be the rooftop of the town hall in Bressanone. The view from the rooftop was classic Südtirol. Behind Kinch's trio (Nick Jurd of the UK on bass; Jason Brown of the USA on drums) were the church steeples and clock towers of the town. Farther behind them were, of course, the steep, emerald-green hills. Most of what Kinch played came rom his 2019 album The Black Peril. His sound on both alto and tenor saxophones is a brilliant wake-the-dead bray. His long, looping, plunging solos were well worth the 40-minute train ride from Bolzano.

The Gărâna Jazz Festival was next. That this festival exists at all, in a tiny village (pop. 122) on a mountaintop in the Carpathians in southwestern Romania, defies logic. But many jazz festivals in Europe defy logic. Twenty-six years ago, someone put on a jazz concert in the village's only restaurant. (It is called "La Rascruce." It is still there.) The concert was a success, so they did it again the following year. It grew. The festival's director, Marius Giura, claims that Gărâna is now the largest outdoor jazz festival in Eastern Europe.

Almost everything takes place in Poiana Lupului ("the wolf's glade"), an unkempt field near the village. There is a real stage, and a real sound system, and even video screens. But it is a hardy variety of jazz fan who comes to Gărâna. There are few places to stay. People camp out. The roads to Poiana Lupului are lined with tents. A crowd of about 2000 sits on rows of logs. Some bring camp chairs. It is cold at night and sometimes wet. No one cares. Kids and dogs run around between the logs. Old men pass around clear plastic bottles containing tuica (Romanian white lightning, made from plums). At the back, behind the logs, are food kiosks and picnic tables. You can buy a dinner of rich Romanian goulash for 27 lei, less than six bucks. They ladle it into metal bowls from huge steaming, bubbling vats.

Bill Frisell, Charles Lloyd, Reuben Rogers, Gărâna Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

Poiana Lupului is orders of magnitude funkier than the MS RheinGalaxie or the garden of Palais Toggenburg. Yet Gărâna has its own sweetness. The vibe is relaxed and communal. And the music is even better than the tuica at making you forget the cold. The opening act was no less than Charles Lloyd & the Marvels (the #1 small group in jazz per the 2021 DownBeat Critics Poll). They played while it was still light. Bob Dylan's "Masters of War" was an appropriate choice for our world's present moment. They turned it into a wild ceremony, an ecstasy of protest. The crowd loved it. The Marvels are Lloyd's guitar band. Bill Frisell played his enigmatic, fragmentary, proprietary songs. Greg Leisz, on pedal steel, played ringing lines that filled the glade with poignance. As for Lloyd, 84, rejoicing emanates from his soul, His tenor saxophone sound is an emanation of pure spirit. He can still stop time as he lingers and hovers over a melody. Then he carries you aloft as he soars to a crescendo.

Håkon Aase, Auden Erlien, Mathias Eick, Erland Dahlen, Gărâna Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

The whole first night of Gărâna was epic. Lloyd's quintet was the only American band. The remainder of the long program contained four groups from Norway, three of which were world-class. Mathias Eick may have the purest, most ravishing trumpet sound in all of jazz. Violinist Håkon Aase has become an important Eick collaborator in recent years. Often, Aase took Eick's flowing lines and turned them into urgent stridence. But whenever Eick took over again, he brought back the melancholy, which eventually ascended toward hope.

Eivind Aarset played with two drummers, Wetle Holte and Erland Dahlen. (Dahlen also played with Eick. Two weeks earlier, Dahlen had played in Monheim with Stian Westerhus. He is in demand because he is a monster.) Aarset and Eick also shared a bass player, Audun Erlien. I had heard Aarset live once, in Norway, and didn't think I liked him. He killed me in Gărâna. Most tunes started innocently and got gradually ominous as Aarset's guitar bit into the cold night air. His band was all about atmosphere and mood, but the moods were varied, sometimes expressed in a whisper and sometimes erupting, with two drummers thundering and Aarset keening.

Håkon Kornstad performed the unique concept that he is now known for: His clarion tenor saxophone plus his operatic tenor singing voice, in a program of Schubert, Wagner, Strauss, Verdi, and Charlie Chaplin ("Smile"). It sounds impossible. It was beautiful.

Verneri Pohjola at the Gărâna Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

The second night started with a gimmicky, grandiose pianist, Kari Ikonen. Things improved with a solid recital of modern mainstream jazz guitar from Arne Jansen. Then things improved dramatically with the appearance of Verneri Pohjola of Finland, who ranks among the elite trumpet players in Europe. He played songs from The Dead Don't Dream, on Edition, one of the sleeper jazz albums of 2020. He performed with the rhythm section from the record: pianist Tuomo Prättälä, bassist Antti Lötjönen, and drummer Mika Kallio. Pohjola played long veering runs or created designs by juxtaposing forms in irregular shapes. Like all the best trumpet players, he has an instinct for the climactic. Wherever he began and however he proceeded, he usually arrived at shattering concluding announcements. Prättälä, with his sudden clusters and ambiguous, spilling digressions, was important to Pohjola's overall impact.

Alexi Tuomarila at the Gărâna Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

Pohjola is on the international jazz radar. His countryman, Alexi Tuomarila, is not but deserves to be. He should have broken through in 2009, when he appeared on Tomasz Stanko's ECM album Dark Eyes. But Stanko disbanded that band after one album. Tuomarila's trio closed the second night of the festival with a commanding performance. Music flooded from his piano and washed over the crowd on logs in huge waves. The tall conifers surrounding the glade, black against the pale night sky, seemed to tremble. Tuomarila is a symphony orchestra of a piano player.

For me, the Gărâna festival ended with Tuomarila's great set. I tested positive for COVID the next morning. I had never had it before. I missed the last two days. My symptoms were mild. I made it home in one piece. I'm not sorry I went.

The war in Ukraine never affected my trip. The Ukrainian border with Romania is about 800 miles north of Gărâna, on the western side of both countries, and Russia's appalling violation was mostly taking place in the east. I met some Romanians who had encountered Ukrainian refugees, but they were only passing through on their way to Poland or Hungary.

A purpose of this narrative has been to render some moments from three extraordinary, dissimilar experiences, to provide some insight into the range and strength of the European jazz scene. A second purpose has been to make the readers of Stereophile aware of what they are missing if they never make a jazz-festival pilgrimage to Europe. That pilgrimage awaits you all.

- Log in or register to post comments