| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

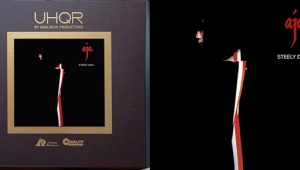

And this review is valid regardless of whether the LP is ultra-rare and difficult to obtain. You are showing over time that ERC is providing an extreme level of fidelity to all aspects of their products.

I really wish I had the cash and the timing to get this. A nice reminder next time.