| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

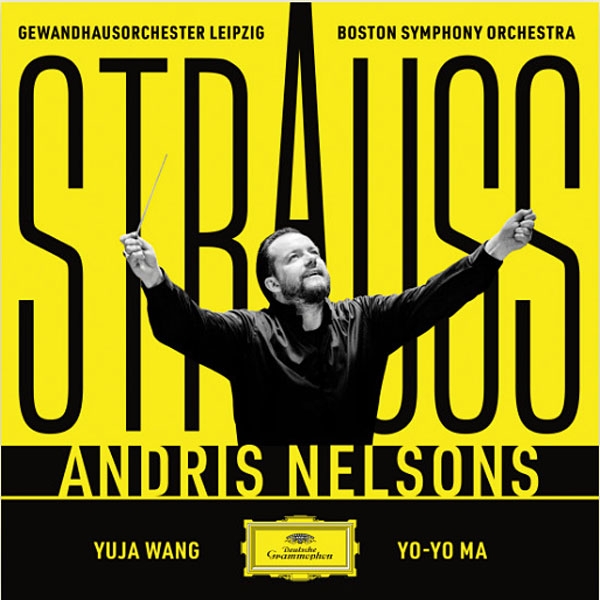

Recording of June 2022: Richard Strauss: Orchestral Works

Richard Strauss: Orchestral Works

Boston Symphony Orchestra, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Andris Nelsons, cond.; Yuja Wang, piano; Yo-Yo Ma, cello

Deutsche Grammophon 486 2049 (7 CDs, auditioned as 24/96 WAV), 2022. Various prods. and engs.

Performance *****

Sonics ****½

Boston Symphony Orchestra, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Andris Nelsons, cond.; Yuja Wang, piano; Yo-Yo Ma, cello

Deutsche Grammophon 486 2049 (7 CDs, auditioned as 24/96 WAV), 2022. Various prods. and engs.

Performance *****

Sonics ****½

At last, a box set of the orchestral works of Richard Strauss to rival the classic analog traversal from German conductor Rudolf Kempe and the Staatskapelle Dresden: a heaping helping of orchestral blockbusters, 93 tracks of music that, for color, splash, dynamic impact, fantasy, romance, wonder, and thrill, are without peer in the classical canon. Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Dons Juan and Quixote, Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's Journey), Death and Transfiguration, Salome's sensational "Dance of the Seven Veils," and Also sprach Zarathustra—Stanley Kubrick's journey to another galaxy, here propelled solely by sound—are but a few of the works on this recording. This is music that, for sheer impact, rivals that of Wagner and Mahler, but, where those composers plumb depths of despair and hopelessness, Strauss frequently leaves us smiling at some of the most seductively charming romantic music ever written.

Without question, Kempe's many recordings bear the hallmark of Straussian authenticity. Kempe played oboe under Strauss in the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig—the "Mendelssohn" orchestra Strauss first conducted at age 23—then went on to take over the Dresden State Orchestra, to which Strauss dedicated Eine Alpensinfonie. Nelsons was born in Latvia 29 years after Strauss died, but he currently conducts two of the greatest orchestras that Strauss conducted in his lifetime: the very same Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig, which gave the premiere of the delightful ballet suite Schlagobers (Whipped Cream) under Bruno Walter, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which Strauss conducted in 1904.

But Nelsons has far more than that going for him. As the master of Gemütlichkeit, that German state of coziness that signifies warmth, peace of mind, good cheer, and a sense of belonging, charm waltzes through Nelsons's DNA. His performance of the Concert Suite from Der Rosenkavalier is blessed with grace, lift, and lilt. Around the bloated bombast of the boorish Baron Von Ochs—pronounced "Ox" for good reason—and the wistfulness of the Marschallin, Nelsons weaves a spell that leaves us dizzy with delight. His music for the budding love between the young Octavian and Sophie immerses us in a universe where every sight, sound, and gesture is redolent with the perfume of wonder and innocence. Only the death hinted at in Strauss's miraculous Metamorphosen—the death that crashes down at the end of Salome—suggests that romance, like life itself, is transitory.

As a study in recorded contrasts, listen to the start of Nelsons's Also sprach Zarathustra. With due respect to the Age of Living Stereo and producer Jack Pfeiffer, those who consider Fritz Reiner's recording of this music the end all/be all of Strauss recordings will most likely move on once they've heard Nelsons's Leipzig rendition in high resolution. Not only is the percussion far more intense, the organ more floor-shaking; Nelsons does wonders with the stuff that follows that initial bombast. In an opening Strauss described as "Sunrise," where humans feel the power of God, he proceeds at half Reiner's speed. Perhaps influenced by Giuseppe Sinopoli's marvelous traversal, Nelsons approaches every note with wonder. As the Leipzig strings rhapsodize at their silken finest, he gives us the aural equivalent of the arrival of First Light. Imagine the experience of someone blind since birth, who, after an operation to restore their vision, has the bandages removed in the early morning hours, just as the sun clears the horizon. Imagine ever-fresh sight and sound filling them with awe, and you'll begin to sense how extraordinary Nelsons's performance is.

Nor is Nelsons solely about charm and wonder. He may not be as savage as Reiner during Salome's wicked seduction, but most of his climaxes are as thrilling as it gets. His storm in Eine Alpensinfonie, recorded in far-off Boston, is fabulous, and his family dispute in that orchestra's rendition of the Symphonia Domestica is a riot. If anyone can convince us that the countless critical dismissals of Strauss's depiction of life in his echt bourgeois household miss the mark, it's Nelsons and the BSO. The over-the-top Finale left me applauding—literally. The better your system, the more you'll cheer. While not every recording is exemplary—spot miking is occasionally overdone—the detail, sheen, and sonic splendor are first class.

If Nelsons's set is not quite complete—it lacks the seldom-recorded violin concerto, two horn concertos, the oboe concerto, the duet concertino, the Suite from Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, the Josephslegende symphonic fragment, the Dance Suite from Keyboard Pieces by Couperin, and Panathenaenzug—it more than compensates with works that Kempe omits: the Symphonic Fantasy on Die Frau ohne Schatten, 4 Symphonic Interludes from Intermezzo, Festival Prelude for Organ and Orchestra with Oliver Latry on organ and the combined forces of Nelsons's two orchestras, and the Love Scene from Feuersnot. Operatic, yes. Imperative, absolutely.—Jason Victor Serinus

- Log in or register to post comments