| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Graham Model 2.0 tonearm Page 2

Mechanical comparisons

Worried about a unipivot's behavior on warped records? Graham's tungsten "outriggers," angled at 23 degrees—the same as the headshell offset—stabilize the arm much like a high-wire walker's pole. And since the azimuth is adjusted by screwing the two tungsten weights in and out, the adjustment is keyed to the offset angle (Graham has a patent on this); thus, the cartridge moves in the desired plane.

Worried about a unipivot's behavior on warped records? Graham's tungsten "outriggers," angled at 23 degrees—the same as the headshell offset—stabilize the arm much like a high-wire walker's pole. And since the azimuth is adjusted by screwing the two tungsten weights in and out, the adjustment is keyed to the offset angle (Graham has a patent on this); thus, the cartridge moves in the desired plane.

The Graham's tracking ability and stability are superb by any standard. The new locking-collet system is a major improvement over the old design, and the new mounting system ensures a rigid mechanical ground to the turntable plinth, something the 1.5t couldn't claim. Is this important? Here, again, there is disagreement. Some say yes; others say that, in a well-damped armtube, any unwanted vibrations are turned to heat before they can get anywhere near the plinth. However, drilling the armboard accurately is critical: if you don't, you can't use Graham's ingenious, easy-to-use, and dead-accurate overhang-adjustment system (which has been described too many times in print to repeat here).

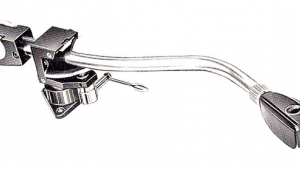

The interchangeable armwands, using an aerospace-sourced Bendix connector at the pivot housing, make swapping cartridges a less-than-five-minute job—a major convenience factor for those who use a variety of cartridges (playing 78s, or less-than-pristine LPs, etc.). Having the bearing in line over the mounting platform ensures a mechanically stable platform. The armwands themselves are as well-damped and mechanically inert as you'll find in any tonearm.

The negatives: If you feel that any connector, no matter how high its quality, affects the mechanical integrity of an arm, you won't be comfortable with the Graham. Having lived with one on and off for four years, I have no such reservations. There are two electrical breaks between the cartridge and the preamp on the Graham—one at the armwand connector, and one a DIN connector under the arm. If you're made uncomfortable by two breaks in the ultra-low-level signal path, the Graham—and the VPI, for that matter—may not be to your liking. Again, based on experience, I have no such reservations.

Finally, there's the issue of silicone damping. Why this is a controversial issue for some audiophiles escapes me. Any gearhead (eg, me) will tell you that, without shocks, your car is going to bounce like crazy—even on a smooth road. The same is true of a tonearm. The cantilever is a spring, and it needs a shock absorber to go along with it. Ideally, you should apply the damping at the headshell. Only Max Townshend's arms and Shure's V-15VxMR cartridge currently accomplish that. Applying damping at the pivot point is a compromise, but it's better than nothing, and it's how many arms do it. With the Graham, you inject silicone into the bearing cup.

Regarding cartridge setup, I like to corroborate it with another gauge—one with hashmarks like a Wallytractor cartridge-alignment gauge (see "Analog Corner," November '97)—to be sure the cantilever rides parallel to the grooves. In any case, the Graham's setup procedure is easily the most accurate and convenient of any I've tried.

Sound

Tonearms are fairly straightforward mechanical devices with an easily defined job, and whose behavior can be predicted, described, and reasonably well measured. This is not to say you can predict how an arm will sound just by its design or measurements, but I guarantee you: If an arm's vertical resonance is determined to be 25Hz, it will roll off the bass below that point.

For this review, I compared the Graham with the Triplanar V Ultimate tonearm. Both of these arms measure well, with both vertical and horizontal resonances in the ideal 8-12Hz region with the cartridges I used. Both behave well on warped records, and both provide secure, rigid platforms from which a cartridge can carry out its function. Both feature easy-to-use cueing devices, and each is a pleasure to operate and optimize. And both are fun to watch working.

But they do sound different. It's been déjà vu all over again since I did a shootout like this in The Abso!ute Sound four years ago with the 1.5t and the Triplanar IV Ultimate. Back then, with far less reviewing experience and technical expertise—and less bass extension in my system—I found the Triplanar to have a wider, "more explosive," more airy soundstage, and the Graham to present the images with more body and three-dimensionality. I found the Triplanar to be "more aggressive" in the upper midrange, the Graham more liquid and "reserved." I also thought the Graham's bass extension, and its ability to portray images "in three dimensions," were superior.

So now what?

Until I heard the Graham 2.0, the Immedia RPM 2 set the standard for dynamic explosiveness, deep-bass extension, control, timbral and textural authority, and palpability—and by a wide margin. The 2.0's bass embarrassed that of the Rockport 6000, which I'd found to be the equal of the Graham 1.5t in that department. (Bad choice of reference! But what did I know then? This is, after all, a learning experience. The Rockport is being upgraded with a new, more massive armtube that will bring the vertical resonant frequency down, thus improving the arm's low-frequency extension. Unfortunately, I didn't have Hi-Fi News & Record Review's Test Record at the time I reviewed it, in May 1996.)

- Log in or register to post comments