| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Plinius SA-100 Mk.II power amplifier

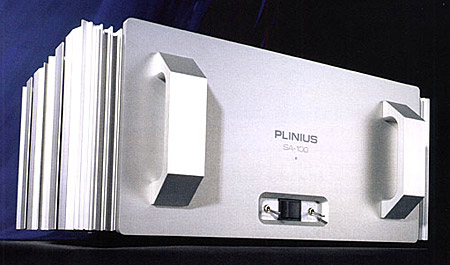

Man, you've got to watch out for those preconceived notions—they'll kill you every time. For the last several years I've seen Plinius amplifiers at hi-fi shows and—even though I didn't know the first thing about the company or its products—figured that I knew what they were all about. Spotting their brawny façades festooned with feathery heatsinks, I smugly assured myself that they were some kind of antipodean pretender to the muscle-amp throne—Krell or Threshold wannabes.

Then Fanfare International's Scot Markwell cornered me at the 1996 Winter CES to ask if Stereophile would be interested in reviewing some Plinius gear. (I should explain that Scot used to do my job, more or less, when we both worked at The Abso!ute Sound—and I never could resist his wheedling.) "Ulp. Sure, I guess...sometime," I stammered. Three days later, an SA-100 arrived in Santa Fe—where it lingered, waiting for me to get around to doing my duty. And lingered. And lingered.

Finally running out of excuses, I took the Plinius amp home and inserted it into my system. I know you're way ahead of me here, but it was nothing like my preconceptions—it was sweetly articulate, airy as all get out, and—yes!—authoritative as could be. So much for my finely tuned instincts.

The early years

Although its roots in New Zealand go back nearly 20 years, Plinius does not have a high profile in the US of A—yet. Plinius Audio Systems was founded in 1980 by Peter Thomson, a mechanical engineer then working for the Hydro Electric Commission in Hobart, Tasmania. The first amplifiers produced were an 80Wpc dual-mono power amplifier and a moderately small but high-quality preamplifier: the Plinius 11 and 111, respectively.

"The original design was developed both laterally and vertically for the next seven years," Thomson explains. "The 111 amplifier was available as the 3100 in A, B, and C versions right up to 1993, but other designs were introduced along the way. In 1983 the first monoblock designs were developed, and in 1986 class-A operation was first introduced. The class-A designs were the Ma100 and Ma102 models, which paved the way for the first stereo class-A design, the SA-50. The SA-50 was the forerunner of the SA range, which now includes the SA-50/2, the SA-100/2, and the SA-250/2."

In 1987 Thomson was joined by Gary Morrison, owner and designer of the Craft Audio Limited line of audiophile amplifiers. The two formed Audible Technologies Limited, which produces the Plinius amplifier line. A new approach involving the pursuit of asymmetrical circuit design was soon begun—an approach which is now the building block of all Plinius designs.

As Thomson tells it, "We discovered in 1989 that an asymmetrical output stage sounded better than a symmetrical one. Since then we have evolved our designs based around an overall asymmetrical topology. We believe that this is more in harmony with the nature of an acoustical wave, and that the inevitable effect that an amplifier has on the signal passed through it will therefore be a musical one."

Peter was solely responsible for the electronic and cosmetic development of Plinius products until 1987, when Gary Morrison took over as Chief Development Engineer and co-director of the company. Peter and Gary are still both responsible for the conceptual development, while Gary is responsible for making it happen electrically.

A peek beneath the skirts

The SA-100 is a beefy design—though much of its bulk consists of the huge heatsinks on its sides. The front panel has a small cutout in which nestles a large rocker-type on/off switch flanked by two lever switches: one toggles between mute and operate, the other between class-AB and class-A operation. The rear panel has four pairs of brass five-way binding posts—two pairs per channel. Some high-end cables have begun to sport unbelievably thick spade lugs, and not every binding post can accommodate them—these can. What's more, their brass nuts allowed me to really get 'em tight. There are both RCA and XLR inputs.

In addition, the SA-100 has an unusual feature called an ACS (Amplifier Configuration Selector). This rotary switch, located between the XLR inputs, allows you to choose the amplifier's mode of operation: RCA stereo, RCA bridged mono, XLR balanced left and right (stereo), or XLR balanced mono. Mains connection is through a standard EEC modular plug.

When I asked Peter Thomson why Plinius offers a choice between class-AB and class-A operation, I expected some sort of complex distinction between the types of listening involved. His answer was refreshingly straightforward: "The class-AB option is primarily intended as a standby mode, allowing the amplifier to be ready for use at any time without consuming the large amount of energy that a class-A amplifier usually does. The AB mode is fine for noncritical listening; its use is less wasteful of energy resources, and ensures a longer amplifier life because of lower thermal aging. All Plinius amplifiers benefit from very long break-in times, and must be left running to maintain the achieved sound quality. Being able to switch to class-A for serious listening is a major benefit."

I'd put off the SA-100's review for so long that Plinius had changed the amp's output bias before I got around to listening to it. This meant I had to re-bias the output transistors myself, during which process I rooted around the amp's innards, impressing myself thoroughly with the quality of the parts utilized, as well as the high standard of build. The Plinius bears comparison with the best-built amps I've seen.

"The SA-100 topology looks quite conventional at a casual glance," Thomson declares, "but the essential elements, those that affect the signal most, are asymmetrical in their configuration. As with most solid-state amplifiers, the input stage is a dual-differential pair; this level shifts and drives a voltage amplifier, which in turn drives a series of drivers and the output devices. The output stage is also asymmetrical and uses only NPN devices. The power supply is split into a common unregulated section for the drivers and output stage, and a regulated section for the input and voltage amplifier stages."

Don't it know the words?

The first thing I heard when I inserted the SA-100 into my system was an overwhelming hum. I'd been using MIT balanced 350 interconnect for the long run between my preamp and power amp, but while in professional audio use there is (purportedly) a firm standard regarding the grounding scheme of XLR connections, this is not so for home audio cabling. The SA-100 and my reference MIT were clearly not compatible. So I substituted a single-ended run of Monster's new M100i—which proved to be surprisingly good, as well as a bargain.

Ahhhh. Other than the slightest amount of transformer rattle, the system was now dead-nuts quiet. Moreover, it was making a glorious noise. Vox Aeterna (Fontalis ES 9902), a compilation of vocal recordings led by Jordi Savall, was rendered with phenomenal clarity and warmth. I felt I could hear deep within the vocal harmonies—so deep within that I entered a trance-like state in which I turned off my conscious analysis of the event and just experienced it. This is easy to do with live music—some might even argue that that's the whole point—but I find it far harder when listening to a recording, and more difficult still when reviewing.

I could hear clearly the differences wrought by the changing venues, the different ensembles involved, and even the different recording practices—the SA-100 is a champ at rendering detail—yet none of these differences overwhelmed my deep sense of musical involvement.

Chico Freeman's Still Sensitive (India Navigation IN 1071 CD) is a wonderful recording: immediate, deeply personal, and quietly impassioned. The Plinius lovingly preserved these qualities, but also placed each member of the quartet precisely in space, and re-created them life-sized and full-bodied. This meant that John Hicks's piano occupied the better part of my listening room, and that Cecil McBee's bass was as dark and deep as could be.

Sometimes we forget that sounding real doesn't necessarily mean sounding good. Mule (Fat Possum/Capricorn 42090-2), by Paul "Wine" Jones, reminded me of this—with a vengeance. Mule is contemporary electrified Delta blues. The band, consisting of two electric guitars, electric bass, and drums, thrashes its way through Jones's songs with raw immediacy while he shouts himself hoarse over the din. To hear this disc is to recognize it instantly for what it is—the true sound of a bar band on a Saturday night. Compared with, say, Eric Clapton's Cradle, this disc sounds downright ugly: You won't find fat guitar tone or imaging or soundstaging. But none of that matters. There's more passion and life and integrity in Mule than in Clapton's last 10 records—and the Plinius got all of that right, too.

After about 20 hours of continuous operation, the Plinius was almost too hot to touch, and I don't just mean the heatsinks—the top-plate and front panel were cookin' too. This, in and of itself, didn't really present a problem, since I had the amp out in the open—although I advise anyone planning on placing the SA-100 within a cabinet or closet to give it lots of room, or maybe even a venting fan. No, the problem was that the amp was now creating hum through the speakers, and the longer it operated, the louder the hum. I spent some time experimenting with different grounding schemes to no avail, so I called Scot at Fanfare and requested a new sample.

In the 12 months since I received my first sample of the SA-100, Plinius had revised the amplifier extensively. The company has changed their transformer supplier, and now pots the transformer as well as suspending it from a steel shelf (rather than bolting it to the bottom of the aluminum chassis). The rectifiers have been moved farther away from the input circuitry.

The first thing I noticed upon switching on the newer sample was that the slight transformer hum exhibited by the other unit was now gone. Unfortunately, I still heard a mild electronic hum through the speakers. It was quite faint, but if I strained, I could hear it from my listening position. It was quieter than the generator noise from my refrigerator, for example, but, in true audiophile fashion, I obsessed over it.

Peter Thomson sympathized. "There is always a problem with toroidal transformers and mains—they seem to be very susceptible to any distortion on the mains, and this causes a change in the hysteresis and the flux density. The distortion can be caused by something many miles away: a switch-mode transformer, large industrial application, or any one of many different things. A hot-air gun in our factory can make an SA-250 just about leap off the bench—and this is when it is plugged into a totally different power circuit. I myself have never had a quiet amplifier in my house—not one in 17 years—yet the same amplifier four miles away at our factory is dead quiet."

Wondering if there was some electrical device within my house causing the hum, I unplugged all my halogen lights (even though they were on different circuits). I still had hum. I then turned off all of the circuit breakers other than the one running the hi-fi. I still had hum. I unplugged all non-stereo devices that share the same circuit as my rig. Sure enough, I still had hum. So I powered everything back up and listened.

I was totally unaware of the hum while music was playing, as I am with tube roar, groove hiss, or any other steady-state noise. Quite simply, I loved the Plinius for its ability to make me care about the music played through it. Some may scoff that I am merely imagining that some amplifiers do this better than others—but in my experience it is so. The Plinius is in the first rank of those that excel at this quality.

I also loved the portrayal of detail that the SA-100 was capable of—detail that never overwhelms the overall musical gestalt, but rather adds enormously to it. Nor, for all its sweetness, was the Plinius a shrinking violet. The amp had tremendous power reserves and proved practically unflappable.

Just last night I was listening to Dave Holland's Conference of the Birds (ECM 78118-21027-2), one of the greatest free-jazz recordings of all time. "Q&A," the disc's second track, begins with a playful drum solo by Barry Altschul that sounded so present and alive that my wife was drawn out of another room, fooled into thinking the drums were real. I laughed at her, secure in the knowledge that she hadn't seen me nearly jump out of my skin, startled by the certainty that those drums were in the room.

Summing up

In terms of pure sound quality, the Plinius SA-100 is worthy of consideration by any music lover. I fell hard for its airy, warm, detailed—yet decidedly easy to listen to—presentation of music. Even though it replaced the $35,000/pair, state-of-the-art Krell Audio Standards in my system, I never felt as though I were suffering—the Plinius's virtues charmed and satisfied me. The quality of build and engineering are truly impressive, making me want to try more Plinius gear as soon as it's available.

As for my problems with hum, I'm going to send the SA-100 to some other Stereophile reviewers and let them report back with their experiences, which may very well contradict mine. I'm also interested in whether or not my second sample will hum on the bench when TJN tests it—it probably won't, just to be perverse.

At any rate, I strongly recommend a home audition of this amplifier, just to find out whether or not it will react to something in your wiring. But by all means do audition it—the SA-100 is one hell of an amplifier.

- Log in or register to post comments