| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Nicely done RB!

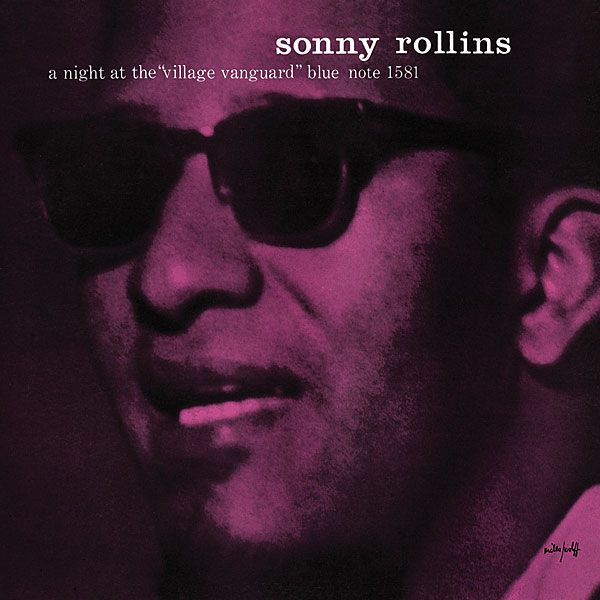

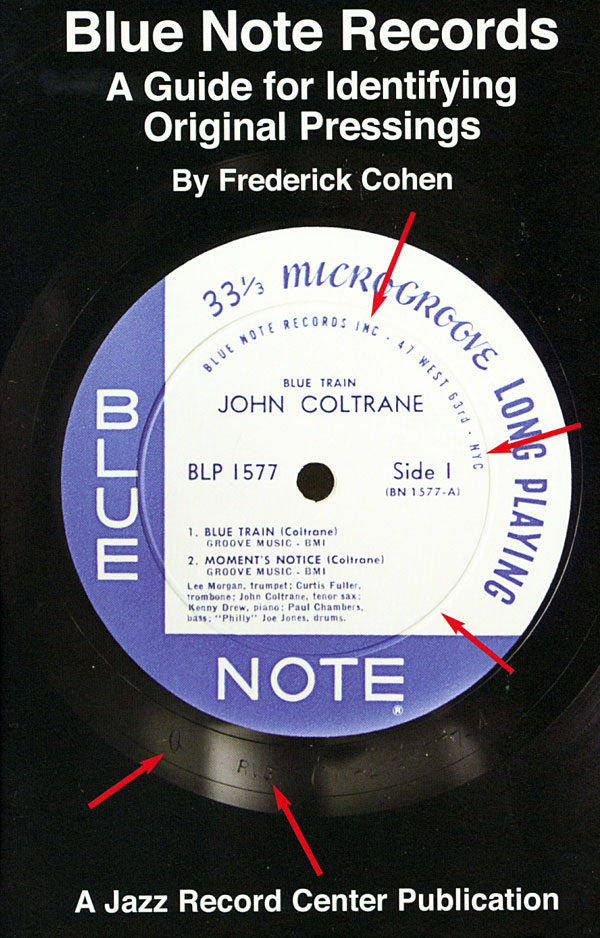

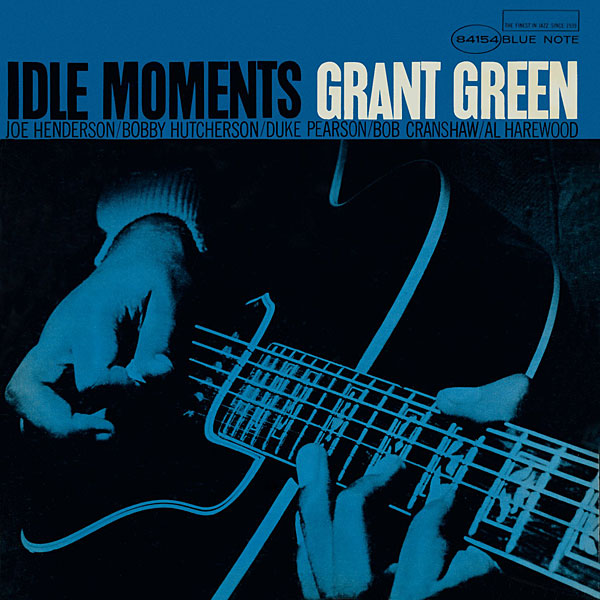

I love Blue Note. I feel the company represents the very best in Jazz. Big collector of CD titles, especially, 1st pressings. I really enjoyed this article, it is interesting how Don Was is at the helm. I think he is doing a great job.