| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

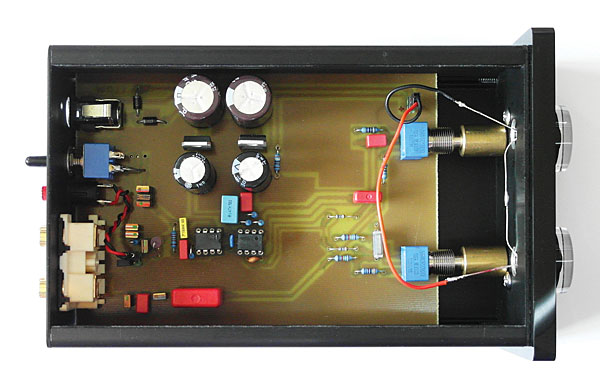

This is the only audio device I've ever seen that uses Gibson speed knobs on its pots.

It was time to make a move, so I set off on my journey through the past: Oscar Peterson on RCA (1952), Earl Wild on Varsity (1952), the Chigi Quintet on London (1951), Jimmy Shand on Parlophone (1950), Pacita Tomás on Spanish Columbia (1949), and many others—including some electrically recorded 78s from the 1940s and '50s. Over the course of several months I found that I quibbled with a very few of the manufacturers' recommended settings—the suggested EQ for old London monos seemed a little too bright, the RIAA settings just slightly too dull—but that's the point of this product's adjustability, isn't it? All in all, Herr Fehlauer was pretty much dead on. His recommendation for old Columbia LPs suited me just fine, taming in particular André Gertler and Paul Kletzki's recording of Berg's Violin Concerto (Columbia 33C 1030). And the recommended settings for Columbia 78s worked very well for my set of Symphonies for Small Orchestra by Darius Milhaud, conducted by the composer and presented in an autographed, limited-edition set issued by the Concert Hall Society (12" red-vinyl 78s, B-11). This is, by the way, one of the best-sounding records in my collection, regardless of medium.

The nicest thing about the Monophonic was the progressiveness—if that's the word—of its controls, combined with its striking clarity: qualities that combined to make it easy to dial in the settings for records of unknown (or, if you will, doubtable) EQ. A very old 78 of a 16-year-old Jascha Heifetz playing Riccardo Drigo's Valse Bluette, arranged by Leopold Auer (Victor 64758), was transformed in that manner. More so were my beloved Hank Williams 78s, comparatively modern things—such as "Why Don't You Love Me" b/w "A House Without Love" (MGM 10696)—that seemed to thrive at settings of 6.5 and 5.5.

Two months after returning the Monophonic to importer Oswalds Mill Audio, I looked back on the listening notes I made during my time with it. The word wow was over-represented to an extent suggesting that I should simply have a rubber stamp made-up if this product comes my way again. The Monophonic didn't just sound good: It was fun. And it wasn't horribly expensive. And it made my record collection seem even bigger than it is by making it even more listenable than it was.

Indeed: Wow.

With refurbished arms

My first Thorens TD 124 turntable, which I found seven years ago on eBay, came bundled with a little something extra: a Thorens TP 14 tonearm in decidedly rough shape. For that reason as much as for my general wariness of used tonearms—wherein worn or maladjusted bearings might result in record or stylus damage—I put the poor thing to one side and set about pretending my TP 14 simply didn't exist.

But it did. And every time I came across that TP 14—often enough that I began to wonder if it was moving itself from one place in my house to another—I felt guilty for not using it. That guilt, plus the simple need for a plain-vanilla 9" tonearm with which to review cartridges of moderate compliance, compelled me to do something I'd never done before: I completely disassembled, cleaned, and reassembled a tonearm, attempting, in the process, to optimize the adjustment of its bearings. (Unipivots don't count!)

My TP 14 was mounted on its own Thorens TD 124 armboard, integral to which was a cueing mechanism of such Goldbergian (or is it Robinsonian?) complexity that I was horrorstruck: My first chore was to remove as much of that contraption as possible and stuff the dusty linkage into a ziplock bag, where it rests in peace to this day.

My second chore was to mount the TP 14 and its board on my turntable, so I could observe the quality of the tonearm's bearings: an easy test that's well within the capabilities of most hobbyists. All one has to do is bolt a cartridge in place—neither physical alignment nor even the connecting of lead wires is necessary—and then install and adjust the counterweight so that the tonearm "floats" in a level position, more or less parallel to the surface of the record platter. That done, one gently nudges the arm up or down by just a few millimeters, then lets go of the arm and watches to see if it returns to precisely the same position as before. (Keeping an eye on something that's on the background "horizon" may be helpful.) If not, the vertical bearings are either damaged or in need of adjustment. (Performing this test on the horizontal bearings is trickier; often, removing the platter to gain clearance for movement is helpful. Having the stylus guard in place is essential.)

Indeed, the vertical bearings in my TP 14 seemed to be almost hopelessly sticky, although the arm's lateral movement was fine. Even more egregious was a problem with the TP 14's counterweight support, which sagged alarmingly. I traced the problem to a rotted isolation grommet between the armtube proper and the counterweight support, through which was fastened, between the parts, a slender inline bolt. (Auto enthusiasts will note an exact parallel between this structure and the drive shafts of various Alfa-Romeos and BMWs, with their notoriously fragile rubber giubos, or flex discs.) After disassembling the TP 14 and before turning my attention to its vertical bearings, I hunted around in my parts bin and found a perfect, and perfectly soft, replacement grommet. One problem down, one to go.

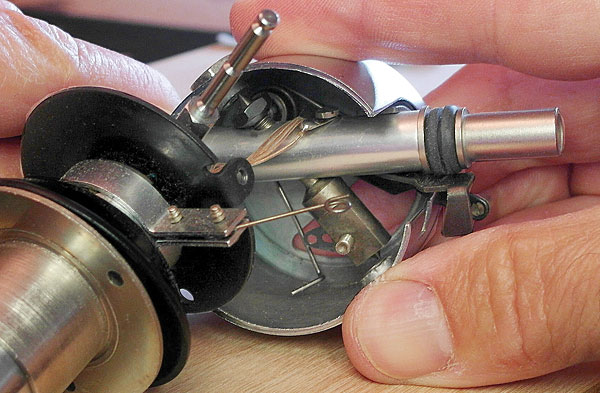

While proper ball-and-race bearings are used for the TP 14's lateral movement, its vertical bearings are of the comparatively crude cup-and-point type. The cup—the stationary part in this design—is no mere conical machining, using as it does three miniature balls arranged in a cloverleaf or pawnshop pattern with a fixed hollow at the center. That said, the execution of the cup is poor: the flanges that hold in place the three balls seem crudely imprecise and obtrusive. (I should pause here and note that EMT, who based their own tonearm designs on those of Thorens, substantially upgraded this part in particular: Although Thorens and EMT tonearms appear superficially similar, a very close look reveals that there's really no comparison between the two.)

After backing out the cups on both sides of the main bearing housing, thus freeing the axle to which the two bearing points are fixed, I cleaned 40-odd years' worth of dust and grime from inside the housing, while taking great care not to stress the delicate signal wires. I had to disconnect the adjustable downforce spring, the free end of which is meant to be inserted into a thin metal plate on the bearing axle. (Thus, if you can envision it, "downforce" is, in reality, "down-and-off-to-one-side force.") I removed those parts that comprised the last vestiges of the cueing system, applied to the centers of the bearing cups an almost imperceptible amount of ultralight sewing-machine oil, and reassembled the TP 14.

Over the next day or two I experimented with different bearing-adjustment settings, accomplished by simply loosening the bearings' exterior lock nuts, moving the threaded bearing-cup retainers closer to or farther from the bearing points by exceedingly small degrees, and retightening the lock nuts. I was able to achieve an acceptably low level of friction by leaving the bearings ever so slightly loose, under which condition the TP 14's armtube, set for zero downforce, could indeed, after being displaced, resume its floating position (although it was perceptibly slow in doing so). Listening tests bore out my preference for bearings that are slightly loose instead of slightly tight—and, counter to my experience with the EMT 997 and other tonearms, the TP 14 sounded better with the tracking force applied by gravity and not the downforce spring, the latter making the sound somewhat coarse. Someday I'll go back in and dispense with the spring altogether—although, like the hated cueing contraption, I'll probably hold on to it forever.

At the end of the day, I thought the TP 14 offered acceptable levels—but no more—of sonic and musical involvement, a lack of touch and nuance seeming the greatest of its shortcomings. These nice-looking arms show up on eBay every now and then, and if you're at all handy, and if the price is right—say, between $200 and $400, depending on condition—you might consider taking the plunge. But if you're looking for a poor man's version of an EMT—or a cheap entry to the world of performance offered by such tonearms as the Ikeda IT-407, the Ortofon TA-210, the Schick, the Shindo, or the best vintage Grays and SMEs—you'll have to look elsewhere.

What the picture of the Monophonic doesn´t show are the glowing red LED indexmarks.

I found them here:

http://oswaldsmillaudio.com/monophonic