| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Analog Corner #245: SME Model 15 turntable, SME 309 SPD tonearm Page 2

SME 309 SPD tonearm: Problems

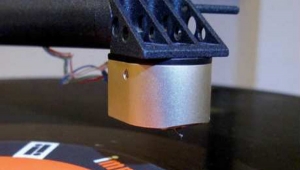

Though the design of the 309 SPD—and that of SME's entire line of tonearms—has been refined over the years, it remains essentially unchanged from the company's first Series 300 tonearms of the late 1980s: After the cartridge pins themselves, between the headshell's cartridge-pin clips and the cable that goes to the phono preamp, there are three breaks in the signal path: an additional set of pins, at the back of the headshell; the connection between the headshell and armtube; and the connection between the DIN socket at the base of the tonearm pillar and the DIN-to-RCA-plug phono cable. Obviously, given a cartridge's minuscule output voltage, the fewer breaks, the better. Yet SME remains committed to this arrangement—though other manufacturers have found ways around it while still offering headshells that are easily inserted and removed.

Though the design of the 309 SPD—and that of SME's entire line of tonearms—has been refined over the years, it remains essentially unchanged from the company's first Series 300 tonearms of the late 1980s: After the cartridge pins themselves, between the headshell's cartridge-pin clips and the cable that goes to the phono preamp, there are three breaks in the signal path: an additional set of pins, at the back of the headshell; the connection between the headshell and armtube; and the connection between the DIN socket at the base of the tonearm pillar and the DIN-to-RCA-plug phono cable. Obviously, given a cartridge's minuscule output voltage, the fewer breaks, the better. Yet SME remains committed to this arrangement—though other manufacturers have found ways around it while still offering headshells that are easily inserted and removed.

Along with creating an additional break in the signal path, SME's set of protruding pins at the back of the headshell creates another problem: Once you've installed your cartridge, the small distance between the cartridge's pins and the headshell's pins can make it difficult to connect one set to the other using the supplied, clip-terminated wires. Some longer cartridges (eg, Koetsus) may not fit at all because the pin distance is too small—or nonexistent.

In addition, since the headshell isn't slotted, you can't twist the cartridge in it to adjust the cantilever's zenith angle. If your cartridge hasn't been perfectly manufactured in that parameter, you're out of luck. On the other hand, the 309 SPD's detachable headshell does have enough play to permit small adjustments in azimuth angle—something the one-piece armtubes of SME's Series IV and Series V arms don't allow.

Those complaints aside, if there's a better-made tonearm for $1900—the difference in price between the Model 15 with arm and without—or one that even comes close, I've yet to encounter it.

Put it all together and . . .

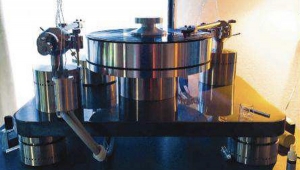

Because I reviewed the Model 15 turntable and 309 SPD tonearm as a package—officially referred to as the SME Model 15A—I can't comment on the individual sound of either one. But I figure most buyers will opt for the $9299 package and be done, at least in the short- to mid-term. Face it: Once you get into analog, the desire is strong to continually upgrade and enhance your experience. Some would say that's an indication of its inherent imperfection—but who cares what they think?

Fig.1 SME Model 15, speed stability data. Fig.2 SME Model 15, speed stability (raw frequency yellow,; low-pass filtered frequency green).

Obviously, given the 15's speed control, I easily got its platter spin at precisely 331/3, 45, and 78rpm. Dr. Feickert Analogue's PlatterSpeed app showed that the 15 spun with ±0.01% relative and ±0.3% maximum absolute deviations (figs.1 & 2, with the green trace low-pass filtered to remove record wow). Those are truly excellent numbers, and should give you some idea of just how rock-steady this turntable sounded.

I used a range of cartridges in the 309 SPD, including the Lyra Etna, the Miyajima Labs Madake, the Ortofon A95, and the Fuuga, the last sounding as magical on top as it had in the Graham Engineering Elite arm on the TechDAS Air Force Two 'table. From top to bottom, the Fuuga has something very special going on: If you can afford to have a few top-tier cartridges lying around, you'd do well to have a Fuuga ($8950).

If I've had any criticism of SME's house sound over the years, it's been that it's somewhat overdamped and thick. Newer turntables from other companies seem more agile in the low end—while still producing good deep-bass extension—and produce a more airy and open top end without added brightness. That's not to say that the SME's top model, the 30/2, is not in the very top echelon of turntables. I'd just be sure to pair it with an open- and extended-sounding cartridge, not one with an overly burnished top, or an excessive bottom end, or a lower-midbass bump.

While the Model 15 with 309 SPD wasn't the last word in bottom-end extension and grip, its bass performance was nimbler, and its top end airier and more open, than those of the bigger and costlier SMEs, though those have a weight and gravitas to their sound that the 15 lacked.

The Fuuga–309 SPD–Model 15 combination produced creamy magic from a new reissue of the perennial Jennifer Warnes favorite, Famous Blue Raincoat, made from the 30ips analog master-tape mixdown of this multitrack digital recording (LP, Cisco/Impex IMP8301). Yes, this recording's sonic fingerprint has "digital" written all over it—or, at the very least, the cool glaze and studio drapings of early-1990s sonic fashion, analog or digital—but, as reproduced by the Fuuga-SME combo, this new remastering had a refreshingly full richness of vocal body and texture that seems missing from previous editions of this album, which tacked an edge onto Warnes's voice. Here, when she belts and lets it all out—which she does a lot—she never sounds thin and stretched.

Of course, when I played this record on the far more expensive combo of Continuum Audio Labs Caliburn turntable, Swedish Analog Technologies tonearm, and Lyra Atlas cartridge ($237,500 total, including the Caliburn's stand), Vinnie Colaiuta's kick drum had noticeably more solidity, extension, and wallop; overall depth and, especially, dynamic contrasts increased; and the entire aural picture became more solid, more firmly embedded in space. On the other hand, this system's more analytical sound brought forward and separated out some of the electronic processing on Warnes's voice, which on occasion became distracting.

But: So tonally well balanced and so rhythmically snappy was the overall sound of the Fuuga-SME rig that I kept hearing myself say, "I could live with this." In "Song of Bernadette," Bill Ginn's string arrangement and piano had never sounded so rich and natural—the result of both the record player and this superb remastering.

Properly designed suspended turntables tend to produce very "black" backgrounds. The Model 15 managed that well, in addition to doing a good job of suppressing impulse-type noises.

A recent recording of Stravinsky's own piano four hands arrangements of his Petrouchka and The Rite of Spring, performed by the husband-and-wife duo of Gil Garburg and Sivan Silver (2 LPs, Berlin Classics 0300669BC), demonstrated both how well high-resolution digital recordings (this one is 24-bit) transferred to vinyl can sound, and how well the combo of Model 15 and 309 SPD could sound playing them.

The image of their piano was ultra-stable, three-dimensional, and tonally seamless from top to bottom. These are not the easiest LPs to track, but each of the cartridges I tried in the 309 SPD rendered the piano without breakup, even in the most difficult and congested passages. The pianissimo passages were delicately drawn, convincingly emerging from the depths of aural blackness. The personality of each cartridge emerged unscathed and without surprises, or even a hint of interference from tonearm and/or 'table, which performed as an essentially neutral combination that committed, at worst, acts of omission apparent only in comparison to a far more expensive and sophisticated analog rig.

Jazz singer Johnny Hartman's Once in Every Life (LP, Beehive BH 7012) was recorded in 1980, not long before his death, in 1983. Here he was backed by such greats as Frank Wess on flute and tenor sax, Joe Wilder on trumpet and flugelhorn, and Billy Taylor on piano. The album has been getting a lot of play in my system, both for its impeccable sound and the suave, relaxed performances. As well as any record I played, it made the case for the SME Model 15A package.

Yes, more can be extracted from this magical recording—more detail, more image specificity and three-dimensionality, more bottom-end extension, more transient definition. But the combo of SME Model 15 and 309 SPD made the case for analog's superior musicality and ability to produce in this listener a relaxed state of mind that no sort of digital sound ever has—not even close.

Conclusions

SME's Model 15 turntable and 309 SPD tonearm are a canny distillation of the company's core values of manufacturing and sound. Unlike the Model 10, the 15 has the ingenious suspension design created by founder Alistair Robertson-Aikman, as well as the essentials of the platter-drive system found in costlier SME 'tables.

Considering its space-saving design, good looks, impeccable build quality, and nimble sound—including rhythm'n'pace abilities that, in my opinion, put it at the head of the SME pack—I rate this combo a complete success: the first major turntable project to come to fruition since Robertson-Aikman's death, in 2006.

Because the Model 15 incorporates design elements, parts, and features—such as the motor-control unit—found in far more expensive SME turntables, it's safe to say that few, if any, startup makers of turntables could possibly make something of this sophistication and high quality of build and features and sell it for $7399. Likewise, although I have a few problems with the 309 SPD arm, if there's another tonearm available for ca $2000 that can compete with it in terms of build quality, features, and sound, I don't know about it. That said, I think the Model 15 would produce even better sound with a better arm, whether made by SME or another manufacturer.

I really enjoyed the time I spent with SME's Model 15 and 309 SPD. In the category of 'table-and-arm combos for $10,000 or less, I enthusiastically recommend this one—especially if you don't have lots of space and want something nonfiddly that has elegantly understated looks, will hold its settings indefinitely, and will work now and, apparently—if previous SME designs are any indication—forever.

- Log in or register to post comments