| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Infinity Reference Standard 1B loudspeaker

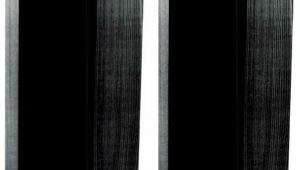

I'll say one thing right off about the Infinity RS-1B: It sure looks as if you're getting your money's worth.

Footnote 1: There is the possibility that the capacitor used as a high-pass filter could contaminate the sound, and this has, in fact, been by some users, who substituted a better capacitor.—Larry Archibald

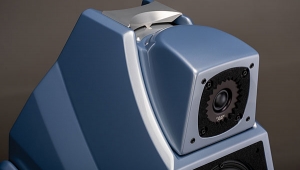

The system comes in five sections: two woofer columns, two upper-range columns, and an active crossover and servo control module. Each bass column contains six 8" polypropylene-cone woofers. Each upper-range column contains seven of Infinity's proprietary EMIM ribbon midrange drivers and four EMIT ribbon tweeters (one of them aiming out the rear, of all things!). System crossovers are at 125Hz (nominal), 750Hz, 3kHz, and 8kHz, and the number of operating drivers diminishes as the frequency goes up, to minimize vertical treble beaming due to phase interference (eg, above 8kHz only one smaller EMIT is driven).

The RS-1B must be biamplified using its own specific crossover/servo module. This has front panel adjustments for woofer crossover frequency, woofer level, bass contour (rising, flat or rolling off with diminishing frequency), LF range (cutoffs at 22, 30, or 36Hz), and amplifier input impedance. The crossover has amplifying circuitry only in the LF section; the signal fed to the upper-frequency amplifiers is passive (unamplified), so there is virtually no possibility of adding nonlinear distortion components to the signal (footnote 1). Because of this, the turnover frequency of the high-pass section varies according to the input impedance of the HF amplifier. (With a given capacitor in series, the crossover point will rise as amplifier input impedance diminishes. When the front panel impedance switch is set to match that of the higher-frequency amplifier (footnote 2), crossovers will occur at frequencies specified in the instruction manual.)

The RS-1B must be biamplified using its own specific crossover/servo module. This has front panel adjustments for woofer crossover frequency, woofer level, bass contour (rising, flat or rolling off with diminishing frequency), LF range (cutoffs at 22, 30, or 36Hz), and amplifier input impedance. The crossover has amplifying circuitry only in the LF section; the signal fed to the upper-frequency amplifiers is passive (unamplified), so there is virtually no possibility of adding nonlinear distortion components to the signal (footnote 1). Because of this, the turnover frequency of the high-pass section varies according to the input impedance of the HF amplifier. (With a given capacitor in series, the crossover point will rise as amplifier input impedance diminishes. When the front panel impedance switch is set to match that of the higher-frequency amplifier (footnote 2), crossovers will occur at frequencies specified in the instruction manual.)

There are also driver level adjustments on the upper-range speaker towers, for "Low Tweeter" (2–5kHz) and "High Tweeter" (8kHz up). It would seem you should be able to get just about any kind of sound from the RS-1Bs you wish, and that proves to be almost the case.

The servo function requires an unusual woofer hookup. The woofer columns do not connect directly to their LF driving amplifier, but instead to five-way binding posts on the crossover module. The module, in turn, connects to the LF driving amp. This arrangement allows the device to compare LF amplifier output signals with signals appearing across the speaker terminals, and to cancel out any detected differences (which would represent back-EMF from spurious woofer-cone motions).

The only potential problem with this servo driving system is the possibility of damaging an amplifier that inverts the polarity of the signal going through it. An inverting amp will turn the crossover's back-EMF–cancellation inverse feedback into positive feedback, driving the amplifier into full-power oscillation. Infinity's manual spells out the risk of this in no uncertain terms, but it doesn't hurt to underscore it here. Most modern amplifiers are non-inverting, but rather than assume yours is, it's best to find out for sure before using it with the RS-I. Most spec sheets will provide this information, as will the amplifier listings in Audio magazine's "Equipment Directory" issue. (Or, again, you could call the amp manufacturer.) If all else fails, you can safely, test the amplifier for polarity, as described in the accompanying sidebar.

While we're on the subject of polarity, I should note that Infinity's comprehensive and detailed instruction manual for the RS-1B perpetuates what I feel to be a myth, albeit a popular one these days. This concerns the importance of overall system polarity ("absolute phase") from cartridge to speakers. As I have pointed out before, I will not argue the fact that polarity reversal in a system often changes the sound, and that one polarity will often sound better than the 'other. But, as far as I know, no one has ever bothered to find out whether that better-sounding polarity duplicates the polarity of the original sounds, or whether it merely enhances other aspects of the sound. (Many loudspeakers, for example, exhibit asymmetrical cone excursion in response to symmetrical input.) Until then, and in the absence of any standard polarity at the recording end of the chain, I feel it pointless to try to achieve absolute phase in the playback system through the use of noninverting components (footnote 3). It makes far more sense to listen to both polarity conditions, and use the one that sounds better with most recordings. If you find yourself bothered by those recordings which don't conform, you can wire a phase-reverse switch into the speaker leads and diddle that to your heart's content (footnote 4).

Despite the unconventional bass amp hookup, installation of the RS-1B is, at least initially, simple and straightforward. Of course, two sets of speaker cables will be required, and if you need to buy another pair, you might consider using a cable outstanding on bass for connecting the woofers, and one whose forte is midrange and treble for the upper-range towers. (I refer you to AHC's wire survey in Vol.8 No.2). But hookup of these speakers is only the first step. For reasons I'll get to later, the system may need many hours—even weeks—of careful adjustment and tweaking before it delivers everything it's capable of.

Sound Quality

My first listen to the Infinities used an Electron Kinetics Eagle 7A on the high end, a BEL 2002 on the low. I was underwhelmed. The low end was excellent, but the upper part of the audio range had problems. First, and most immediately noticeable, was the system's lack of adequate mid-to-lower-middle-range output, which could not be corrected via any of the available driver level controls. The overall sound was rich and luscious, but—pardon the expression—the system lacked balls. And, although there seemed no shortage of high-end range, the sound seemed just a bit slow. There was another problem that I can't exactly explain. My guess is that the system has some exceedingly small, sharp response peaks at the high end, and because of them the RS-1Bs seem to exaggerate any traces of roughness (grundge) in the signal source.

So, I swapped amplifiers. The low end improved a little with the Eagle, and the upper ranges sounded a little less rough with the BEL, but the sound was even more unctuously dead. And, although reduced, that tendency to exacerbate crud in the signal remained.

I recalled that Infinity usually demos their loudspeakers at CES with Audio Research tube electronics, and wondered whether that variety of amp might not be a mandatory adjunct to the RS-1Bs. We've been awaiting delivery of some (promised) Audio Research amps for so long now that we no longer hold our breath, but we had just recently received a pair of Conrad-Johnson's massive mono Premier Fives. So I schlepped those home (90 lbs each, boxed) from the office storeroom and fired them up on the system's high end, with the Eagle 7A on the woofers. Well, sir...

I won't say the Premier Fives transformed the RS-1Bs into a WAMM or into Infinity's own IRS system, but for the first time I began to understand why people have been willing to spend $5295 on this system. These are among the few speakers I've heard in ages that can stand my hair on end!

First of all, the RS-1Bs seem to have no practical upper limit of power-handling capability! They will play at very high levels (like 110dB on peaks!!) without a trace of strain or hardness, assuming of course that you throw enough power at them. (The Premier Fives can throw 200Wpc.) Talk about "digital-ready"!

The RS-1Bs image about as well as any large loudspeakers I have heard. This puts them in the class of the WAMM and the IRS, both of which I consider to represent the state of the art for soundstage presentation and reproduction of depth. The RS-1Bs are the first speakers I've had in my listening room that actually put some of the soundstage (on appropriately-miked recordings) beyond the lateral limits of the speakers—something I did not believe possible except in a room with highly reflective walls (mine are not). They are bettered in imaging specificity by a few tiny satellite speakers and, I suspect, by some curved-panel electrostatics, but only by a small margin.

These are big-sounding speakers, with a gutsy forcefulness that I do not recall encountering in any audiophile system. When a trombone speaks from these, you sit up and pay attention! If you wished to reproduce the voice of God, these speakers could do it. Bowed cellos, synthesizer grunts, and piano bass strings had just the right amount of attack and delineation, and with balance controls properly adjusted, all other musical timbres were reproduced with superb accuracy. No instrument was slighted, and—despite the complexity of the crossover network—the drivers meshed almost seamlessly. (The only discontinuity I could hear, and then only on piano, was the transition from the EMIMs to the cone woofers, at which point the piano strings seemed to lose a little of their "twang.") Massed violins were gorgeously smooth, yet with all the fine-grained gutty edge of the real instruments. Brushed cymbals were open and natural-sounding, and brass and steel were easily distinguished.

The system's low end was particularly impressive. I have never before had a fullrange system in my listening room that would put out a full-level 30Hz signal, but, with their LF response set for Flat, these do it. In the +3dB (at 30Hz) position, the 25–35Hz range was, believe it or not, excessive! Bass quality, too, was excellent, although not quite as controlled as I have heard on (rare) occasions from big transmission-line systems such as the behemoth that Irving Fried used to demonstrate at audio shows. But don't misunderstand me: the RS-1B's bottom is excellent, having immense impact and awesome range. The cannons from Telarc's 1812 CD produced what felt like shock waves!

In fact, impactive sounds are one of the RS-1B's strongest points. The attacks of hard transients—snare drums, rim shots, and xylophone strikes—are razor-sharp, yet the speaker is entirely free from the exaggerated hardness and stridency found in most other speakers with comparable impact capability.

The only areas in which I have heard the RS-1Bs bettered are transparency, realism, and high-end openness and delicacy, all of which are better presented by some fullrange electrostatics, notably the MartinLogan Monolith. For example, the RS-1B's rendition of detail, while awesome, sounded a little heavy-handed, as if sharpness were substituting for delicacy. And while its high end was very smooth, the sound lacked the suavity and musical sweetness of the electrostatics. In the area of realism—the ability to give the impression that real, live instruments are playing—the RS-1Bs did very well, but were not equal to the best I have heard. In comparison, the RS-1B tended to fill in the spaces between bursts of musical sound.

Yet, I continue to be immensely impressed by the sound of the RS-1Bs, and that is what I felt ultimately to be their most outstanding characteristic: they have an "impressive" sound. They are awesomely exciting to listen to, and do an incredible job with bombastic, massive works like Mahler's Second Symphony and the 1812 Overture, and with high-powered recordings like Sheffield's Track and Drum records. But I found them rather less satisfying when reproducing smaller-scaled, more intimate material, such as chamber music and solo guitar. With that kind of music, they still image superbly, making a well-miked guitar sound like a mono recording with stereo ambience (which is exactly right). But that "impressive" quality remains, the music losing some of its gentleness.

There are a few other problems with the RS-1Bs, not the least of which is their setup. These speakers offer so much potential for superb sound quality that all the tweak factors, of little importance in mediocre systems, assume paramount importance. To set up the speakers according to the diagram in the manual, set all controls for Flat and let it go at that, is to throw away half the potential (and half the considerable cost) of the system.

The RS-1B is one of the most revealing systems you can own, which is one obvious reason why it "prefers" tubed amplifiers (with their slight1y soft top) to solid-state's slightly "crisp" top. But this is a mixed blessing, as it imposes almost impossible demands on the cleanness of the program material. In fact, I am not altogether certain the RS-1B isn't still exaggerating grundge in the sound. I have heard slightly better transparency with slightly superior detail from some electrostatics, notably the MartinLogans, and none of them showed any such tendency to exaggerate signal garbage.

One thing is perfectly clear, though, and that is that you are not likely to get the best results from the RS-1Bs unless you use tubed power amps, and the best tubed amps at that. It is probably safe to say that no tubed amp made is too good for this system, which means that when you buy the RS-1Bs, you can probably plan on paying at least an additional four grand or so (the Premier Fives are $6000) for suitable upper-range power amps. (The Infinity woofers require only that the amplifier have high power and high current capability, and the amplifiers that best meet these requirements are solid-state.)

As with any system having such a wide variety of frequency-response adjustments, the ability to obtain almost perfect response is countered by the even greater likelihood of royally screwing up. While there is only one optimum set of adjustments for a given listener, listening room, and complement of associated equipment, there is an almost infinite range of possible maladjustments

and the only way of telling when things are "right" is by ear. This means that, if you are going to get anything better than frustration or endless indecision from the RS-1Bs, you'd better have a very sophisticated set of ears or one helluva competent dealer to install them for you.

For what it's worth, here's how I went about adjusting the controls. First, I set the crossover controls to their (theoretically) flattest positions. Then I turned the woofers off and the tweeters all the way down. Using a variety of recordings whose derivations I trust (including some of my own tapes), I adjusted woofer level for what sounded like the most natural LF balance. (Some of these recordings, for instance, are known to have somewhat heavy bass, so the "correct" setting with the '1Bs gave somewhat heavy bass.) Then I set the Lower Tweeter controls to their "flat" midpoint, and listened carefully to the sounds of violins, woodwinds, and female voices. All were a little too hard, so these controls were backed off until they sounded right. Now all that was missing were the upper overtones. For these, I started adjusting the High Tweeter controls from their lowest position (rather than from "Flat") until vocal sibilants, violin guttiness, and woodwind reediness were in proper balance.

What's "proper" to me may not be so to someone else (and varies a lot on phono sources,' depending on what cartridge you use, though this isn't a problem with CD or tape), but the most important thing to bear in mind is that you can tailor the upper end of this system to sound just about any way you want. (Incidentally, it is essential to do the HF balancing adjustments at your normal listening volume, because the ear's HF response varies according to program level.)

In my room, with my associated equipment, no further response tweaking was necessary, ' but it's possible to adjust the response through the middle-LF crossover region and through the low end via controls on the electronic crossover. Again, these adjustments should be made using a wide variety of perfectionist recordings. Once the response seems to be optimized, leave the adjustments alone unless you experience a consistent problem apparent on many recordings. Using speaker balance controls as tone controls is the surest way of losing sight of which end is up, and of spending the rest of your life trying to tweak the system to a point of perfection beyond that of any one recording.

Room placement and speaker orientation are two other things which take a lot of time to get right. As usual, the manufacturer's recommendation here is only a starting point. Everything from soundstaging to tonal accuracy is affected by the speakers' placement and orientation in a particular room, and only through experimentation over weeks or months will it be possible to get the most out of the system.

Several readers have reported problems with frequent fuse blowing in RS-1Bs. In fact, I managed to blow High Tweeter fuses several times myself during listening tests, often for no apparent reason. The manufacturer's guess is that this is caused by amplifier overload (clipping), but I hardly consider the Conrad-Johnson amps to be hard-clipping amplifiers. That problem remains unresolved. Meanwhlle I urge you to check the RS-1B's fuses from time to time, just to be sure.

Summing Up

All in all then, the RS-1Bs must be ranked among the very best speaker systems that money can buy without going completely overboard. They are not The Ultimate Speaker for everybody, but in view of what they do superbly, I think it fair and accurate to describe the RS-1Bs as the quintessential audiophile speaker system. These speakers do nothing valued by the critical audiophile anything short of superbly! People who get to hear live music frequently, and who value what we have come to call "musicality"—sweetness, warmth, and delicacy—may be better off choosing something else like the MartinLogan Monoliths or the new Xstatic electrostatics, but in so doing they will give up some of the impact and drama that are just as characteristic of live music.—J. Gordon Holt

Footnote 1: There is the possibility that the capacitor used as a high-pass filter could contaminate the sound, and this has, in fact, been by some users, who substituted a better capacitor.—Larry Archibald

Footnote 2: This specification is not always supplied with an amplifier, but can be obtained by a phone call to the manufacturer.—J. Gordon Holt

Footnote 3: Not to mention the foolishness of upgrading or downgrading a component because it is noninverting or inverting. Phase inversion is a characteristic that accompanies all gain stages; even numbers of gain stages in a component will cause it to noninvert, while odd numbers will cause it to invert. Therefore a supposedly bad, inverting, component could be "improved" by adding yet another gain stage! In fact, designers normally use the minimum number of gain stages to get the job done, but that number will vary with the type of component and particular topology employed. Inversion or lack of it becomes even less important when you consider that not only components, but recordings as well, vary in this characteristic: you will never be "right" with all sources and all equipment.—Larry Archibald

Footnote 4: Except with the RS-1Bs, where this procedure would put the midrange-tweeter towers out of phase with the woofers. Blessed are those who own Klyne SK-5 preamps, the only product I know of that allows you to conveniently switch the entire system phase at the preamp.—Larry Archibald

- Log in or register to post comments