| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Did you ever meet Bill Safire? What a pompous arrogant jerk, he thought privelage and position entitled him to lord it over others and throw his weight around. Sorry I couldn't read any more after mention of his name and I'm sure those that ever worked under him would feel the same. Speak as you find, isnt that what they say?

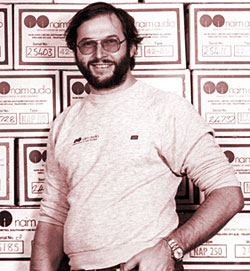

Editor's Introduction: One of the big industry stories of 1985 was the split, both personal and commercial, between the British Linn and Naim companies. Led by

Editor's Introduction: One of the big industry stories of 1985 was the split, both personal and commercial, between the British Linn and Naim companies. Led by