| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Like with others, downloads of music still have me on the fence and non-committal.

Those of us who are repertoire and performance-driven consumers of music stay with our CD collections due to the still-unmatched breadth of the catalog in this medium.

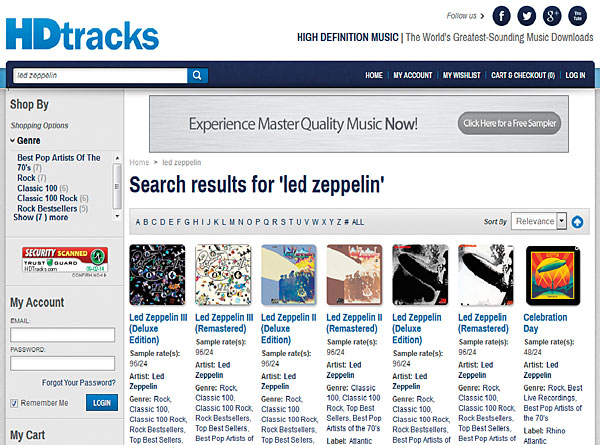

I looked in HD Tacks for what I consider to be the finest Chesky Records recording that I have purchased, the Earl Wild interpretation of Rachmaninov's Piano Sonata No. 2, and 18 of the 24 Preludes (Chesky CD 114). Alas, the recording was not to be found in my search of HD Tracks' admittedly broadening assortment.

It will take time, but while it takes time, many collectors of the classical catalog will return to, and continue to purchase, CDs as the enduring definitive repository of the finest interpretations of works in the classical repertoire. LPs probably occupy a similarly prominent place in the priorities of other music lovers (particularly of the jazz and classical genres).

I am confident that music downloads will continue to grow in their offerings. The critical question remains as to whether seminal works in the catalog will make the cut for what gets added to the catalogs of downloadable music.

Many classical fans will take a CD or LP recording of a critical reading of a work over an average interpretation available for download (however great the sond quality), until such definitive renderings figure in the available catalog of download sites.

Yes, there will be future great works; I'm sure the world has not seen the last of artists of the stature of the greats of the 20th century. Building a catalog of downloadable tracks of these yet-to-be-found artists (and downloads, admittedly, do have some greats among their tracks for sale) will take time and painstaking attention to detail.

I'm keeping an open mind; let's see what happens.