| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Tannoy Dimension TD12 loudspeaker

My friend Harvey Rosenberg, who had more clever ideas in a day than most of us have in a lifetime, was a Tannoy loudspeaker enthusiast. I, on the other hand, had little experience with the brand before 1995, when Harvey invited me to come over and hear his then-new Tannoy Westminster Royals.

Footnote 1: The Voigt driver eventually became known as the Lowther driver, which has changed even less since the dawn of time: It is the horseshoe crab of hi-fi.—Art Dudley

I'm not sure what I expected, although I remember I had to be corrected as to Tannoy's origins: Something about the sound of the name had always led me to think, dully, that the brand was Japanese. As it turns out, Tannoy began life in south London in 1926 when its founder, a man with the improbably colorful name Guy R. Fountain, started making electrolytic rectifiers by combining tantalum and lead alloy—and there you go. (In my defense, the mistake might have been fueled by the fact that Tannoy's biggest and most expensive loudspeakers have always been popular with the audio cognoscenti of Japan. In fact, Japan imports more Tannoy speakers than any other brand.)

I'm not sure what I expected, although I remember I had to be corrected as to Tannoy's origins: Something about the sound of the name had always led me to think, dully, that the brand was Japanese. As it turns out, Tannoy began life in south London in 1926 when its founder, a man with the improbably colorful name Guy R. Fountain, started making electrolytic rectifiers by combining tantalum and lead alloy—and there you go. (In my defense, the mistake might have been fueled by the fact that Tannoy's biggest and most expensive loudspeakers have always been popular with the audio cognoscenti of Japan. In fact, Japan imports more Tannoy speakers than any other brand.)

But getting back to Harvey and his Tannoy Westminster Royals: My first listening impression may or may not have been conditioned—I mean this seriously—by the fact that, when I first laid eyes on them, I wasn't entirely sure the speakers I had traveled to hear were speakers at all. The well-crafted, unabashedly wooden Westminster Royals looked like very heavy china cabinets. But where one might otherwise expect to see an entire row of commemorative plates—perhaps featuring the likenesses of Ron and Nancy Reagan, the crew of the spaceship Challenger, and Diana, Princess of Wales—each Westminster displayed on its single shelf a single plate. On closer inspection, the single plates were single drivers, each marked with insignia in gold leaf.

That first listening impression was extremely positive: For the first and possibly last time in my life, I heard a stereo sound every bit as dynamic as real music. I wound up spending the night at Harvey's, sleeping on the couch in the same room as the speakers, listening until I couldn't hold my eyes open any longer.

That's velvet, isn't it?

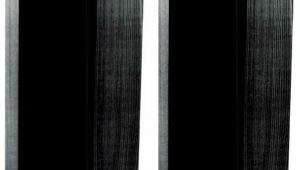

The new Tannoys I was sent for review, the Dimension TD12s, don't look like china cabinets or anything else. They are products of modern thinking. (A bit later, I'll tell you what my wife thought of their impact on our living-room décor.) The important thing for now is that the TD12 retains a link to Tannoy's past: one of its drive-units is actually two drivers in one—a Dual Concentric, to use Tannoy's trademarked phrase.

From the earliest days of their involvement with domestic audio, Tannoy believed that one of the great impediments to making a convincing full-range loudspeaker was the fact that different drivers, covering different portions of the audible frequency spectrum, create wavefronts that tend not to blend well: Their dispersion characteristics clash. They aren't properly time-aligned with one another, meaning that various subcomponents of the resulting complex wave are out of phase with each other as compared with the original. And because these wavefronts are launched from different physical points, the listener's perception of music playback as a spatial event is a hit-or-miss affair, depending on where he or she sits in the listening room. Egad.

Tannoy introduced their solution to those problems in 1947, when Sam Tellig was but a wee lad and the end of World War II made it possible for England to redirect her wartime technologies toward more peaceful things: a one-piece woofer and tweeter, arranged coaxially. In the interest of physical time alignment, its high-frequency driver was positioned behind the throat of its low-frequency cone, thus distinguishing the Tannoy from other coaxial loudspeakers, then and now, where a tweeter is suspended in front of the woofer dustcap. And it differed from its contemporary, the Voigt driver (footnote 1), in that the Tannoy's two vibrating elements were physically and electrically separate from one another: The tweeter neither rode piggyback on the woofer nor shared its voice-coil. Thus: Dual Concentric.

Notwithstanding the refinements afforded by such things as computer-aided design, metal-depositing techniques, and various new polymers, Tannoy's best speakers of today have the same Dual Concentric technology at their core. The TD12 is built around a driver that combines a 1.25" aluminum-dome tweeter with a 12" pulp bass/midrange cone. The dispersion of the former is controlled by a stationary waveguide and by the woofer cone itself, which acts as a horn, the flare rate of which is best described as "compound." In addition to keeping electrical sensitivity high, that probably makes for a much smoother resulting impedance curve than would otherwise be possible. The woofer cone, for its part, has a relatively stiff surround made of impregnated fabric, and it's reflex-loaded via two ports on the back of the cabinet. As supplied, these are filled with foam to provide resistive loading.

On paper, the two diaphragms appear to have been engineered as one with the greatest of cunning—yet because they're electrically and physically separate, some form of crossover is required. Luckily, this has been kept simple: a combination of a third-order low-pass filter with a first-order high-pass, all hardwired, and with a center frequency of 1.1kHz. The result is something that sounds impossible: a single-driver loudspeaker that can be biwired.

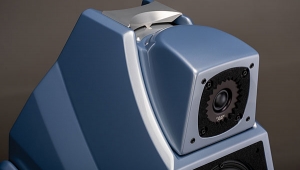

But here's another twist: The TD12, like the other models in Tannoy's Dimension series, isn't a single-driver speaker at all: Tannoy has equipped it with their new SuperTweeter, a 1" titanium dome with a neodymium magnet. The Dual Concentric driver is allowed to roll off naturally at the top of its range, and the SuperTweeter blends in with the aid of a third-order high-pass filter. The center frequency of this compound (acoustical plus electrical) crossover is 12kHz, and the response of the TD12 is claimed to extend way the hell out to 54kHz, where boy bats whistle at girl bats. The SuperTweeter sits in a chunky ovoid housing machined from aluminum alloy and mounted on the main cabinet in such a way that its voice-coil is the same distance from the listener as the other two.

And what a cabinet! Its lines slope and curve, with few parallel surfaces in sight. A cherry veneer that wouldn't look out of place on an expensive Stickley table shares space with metal trim and a black velvet apron, the latter ostensibly to absorb and tame unwanted high-frequency reflections. And because it's constructed entirely of Baltic birch plywood—the baffle is 1½" thick, with 1" wood used for everything else—the TD12 is unusually heavy for its size: a whopping 108 lbs each. Since I have no friends and most of our floors are hardwood, I wound up moving the TD12s around by "walking" them onto a little area rug, sans spikes, then pulling them from room to room like a child pulling a very large toy.

Now I'll tell you why I had to move them at all.

Big speaker, big room

The room in which I do most of my listening—which, in its previous lives, before I bought the house, served first as a master bedroom, then as a dining room—is 12' wide by 19' long, with an 8' ceiling. I place loudspeakers at the far end of this room, firing down its length, and when I install a new pair I rely on both my ears and my AudioControl Industrial SA3050 spectrum analyzer to achieve both the best bass extension and the smoothest overall response.

I started out using my Naim separates with the Dimension TD12s: Playing a 92dB speaker in a medium-small room with 35W or so seemed reasonable to me, and there were no technical clashes I could see. The first record I listened to was the Peter Maag/London Symphony recording of Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream (LP, Decca/Speakers Corner SXL 2060). I was a little disappointed. Even with the Tannoys well into the room and away from the walls, the sound was more colored than that of the similarly priced Quad ESL-989 speakers, whose places they'd taken: boomy bass, and odd dips and peaks throughout much of the midrange. Voices and some instruments sounded dark, and the whole presentation had a slightly hollow quality: obviously, not the results I or anyone else was striving for.

I tried a more delicate record: Joni Mitchell's Blue (LP, Reprise MS 2038). That one fared better, arguably thanks to its comparatively limited frequency range. But still, Mitchell sounded darker and thicker than usual, especially toward the bottom of her singing range, and the piano, which sounds a bit glassy on some of the album even under the best of circumstances, now sounded glassy and thick. Still, I couldn't help but enjoy the music. Rhythms and pitches were just fine.

Setting aside for a moment the matter of tone, I thought the sound of Levon Helm's snare drum on The Band's Music from Big Pink was better than I'd ever heard: The Tannoys did an amazing job of getting across the idea that I was hearing a real human being whap a wooden stick against a drumhead with considerable force.

Footnote 1: The Voigt driver eventually became known as the Lowther driver, which has changed even less since the dawn of time: It is the horseshoe crab of hi-fi.—Art Dudley

- Log in or register to post comments