| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Music Served: Extracting Music from your PC

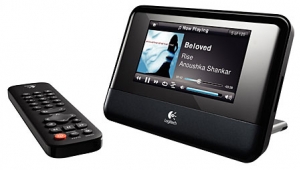

"Physical discs seem so 20th century!" That's how I ended my eNewsletter review of the Logitech (then Slim Devices) Squeezebox WiFi music server in April 2006, and it seems that increasing numbers of Stereophile readers agree with me. In our website poll of January 5, 2008, we asked, "Are you ready for an audiophile music server?" The response to that question was the highest we have experienced: 32% of respondents already listen to music via their computer networks, many using home-brewed solutions, and 44% intend to. We've published a lot of material on this subject in the last five years, and it seemed a good idea to sum it up in this article.

Computer in the listening room?

Two primary questions face an audiophile who wants to integrate a PC into his high-end system. First is which file format to use for ripping the music from his CDs (see sidebar). The second question is whether to put the computer in the same room as the audio system, or in a remote room. The former makes things much easier, but sound quality will be compromised by the noise of the computer's fan and hard drive. (Some computers, such as the cheap Mac mini, have fans that rarely turn on and are therefore inherently quiet.) Remote location of the computer eliminates the noise problem, but introduces more system complexity.

The first option is by far the simplest and cheapest. You need three things: somewhere to back up your music files, such as an external USB2.0 or FireWire (IEEE1394) hard drive; a soundcard, with its analog outputs feeding a line-level input on your preamplifier; and a music jukebox program to allow you to tag, browse, and play your music, and compile playlists.

Many jukebox programs are available, the most popular being Apple iTunes, which runs on both PCs and Macs. Other, PC-centric programs are Foobar 2000, Media Monkey, Winamp, and, of course, Windows Media Player. For the Mac, there are Music Man, Play, and SongBird. Each of these has its advocates, but not all will play all file formats—while iTunes, for example, can't handle the popular FLAC format,1 it's the only program that will play the protected AAC files that can be purchased from the iTunes store. All will rip your music from CDs and search the Web for the appropriate metadata tags, though I prefer to use the free Exact Audio Copy program (Windows only), which allows you to optimize your PC optical-drive operating parameters to deal with error-prone CDs.

These days, most PCs come with a motherboard that handles audio, doing away with the need for an internal or external soundcard. But my experience has been that the analog audio output of these boards is not really of high-end sound quality, the PC's internal environment being electrically very noisy. In addition, PCs older than 18 months or so use the Windows AC97 codec, which doesn't handle high-resolution audio formats optimally. The CoreAudio codec used by Macintoshes running OSX does handle hi-rez music data correctly, however, as does the codec that comes with modern PCs running Windows Vista.

The audiophile has two more choices, therefore:

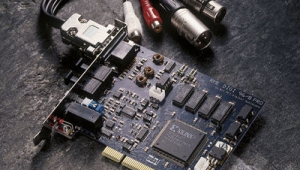

1) A high-quality, therefore expensive, soundcard in the computer chassis, such as the RME HDSP 9652 Hammerfall DSP ($700) or the Lynx AES16 ($625), both of which will handle 24-bit data at sample rates up to 192kHz—ideal for Reference Recordings' new HRx DVD-R data discs, which contain 24-bit/176.4kHz–sampled audio files; or the older Digital Audio CardDeluxe ($399), which is restricted to a 96kHz maximum sample rate.

2) get the audio data out of the computer box using USB or FireWire, and an external converter to convert those data to analog. My favorite solution for this is also the cheapest: the M-Audio USB Transit costs just $80 and works with both Macs and PCs. It converts USB data of up to 24-bit word length and 96kHz sample rate to both analog audio and optical S/PDIF digital audio. The analog outputs are only so-so in quality, but the digital output can be sent to the digital input of a standalone, high-end D/A converter or an A/V receiver. (Some Macs do have optical S/PDIF digital data outputs, eliminating the need for something like the Transit.)

Modern high-end digital processors also feature USB inputs, and Stereophile has recently reviewed four such, all of which we recommend: the Musical Fidelity X-DACV8 ($1500), the Bel Canto e-one DAC 3 ($2495), the Benchmark DAC 1 USB ($1275), and the Grace Design m902 ($1695). The last two, which include very-high-quality headphone amplifiers, were compared by Sam Tellig in the October 2008 Stereophile.

One aspect of USB connections is that almost all the products available on the market allow the host computer to control the flow of data. A PC is not optimized for uninterrupted streaming, and has operating-system housekeeping chores to attend to—while the sample rate of the output data, averaged over a longish period, will indeed be the specified 44.1kHz or 48kHz, there will be short-term fluctuations. These timing variations in the datastream, are called "jitter" and result in increased analog noise and reduced resolution in the reconstructed audio signal. (Once jitter has been introduced, you can never really remove it completely, only filter it.) The USB DACs reviewed by Stereophile vary in their ability to minimize the effects of jitter—read the original reviews for more information.

By contrast, it is possible to operate the USB interface in what is called "asynchronous mode," which allows the DAC to control the flow of data from the PC, which in turn very much reduces the amount of jitter. However, at the time of writing, there were very few USB DACs available that operated in this mode. The least expensive is the Wavelength Cosecant ($3500), which is scheduled for a review in Stereophile early in 2009.

With all of these solutions, it is not always as straightforward as it should be to get "bit-transparent" playback. With the internal soundcards mentioned, they can be used with the ASIO protocol, which bypasses the PC's audio handling altogether. External USB and FireWire devices should be bit-transparent, but you need to make sure your jukebox program has all its "enhancements" disabled, that its volume control is set to its maximum, and that the PC's or Mac's sound-handling parameters are set to not do unnecessary and quality-compromising operations such as sample-rate conversion. (With a PC, check the settings in Control Panel; with a Mac, check System Properties and the Audio/Midi utility program settings.)

- Log in or register to post comments