| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

McIntosh MS750 music server Page 3

I think he's partly right. No, I don't think we audiophiles would rather hear the warts and spots on recordings, but those last little smidgens of air, delicacy—and, yes, even power—are audible through the Ayre not just with DVDs and SACDs, but with "Red Book" CDs as well.

Christian McBride's bass dug deeper through the Ayre—not deeper into the bass, but deeper into the groove. Lovano's tenor sax bit harder, and the sound of the room was more evident in Tyner's piano sound—not a lot, but enough that when I paid attention, I could hear it.

That said, the pace and timing of Stephen's salsa mix was magnificently presented by both the McIntosh and the Ayre. If you thought I was going to say that the Ayre aced the Mac in delivering that salsa beat-itude, I have to surprise you. It sure surprised me. Startled me is more like it—through the MS750, that complex cowbell syncopation absolutely sounded as if it was in the house.

The Ayre did capture with more astringency the overtone bite of Yomo Toro's cuatro on "Que Bien Te Ves," though not by a lot. But in critical listening, that little bit extra can mean the world.

Horses for courses, of course. For the same money, you can buy a single-play, multiformat player, or a music server capable of storing an immense amount of music at your beck and call.

Jump back, Mac!

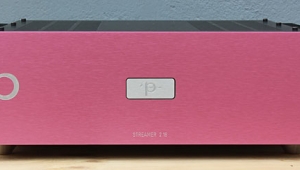

After he measured the MS750, John Atkinson asked me to add some notes on using the music server, via its digital outputs, as a source for a D/A converter. He suggested a known quantity: the $2495 Bel Canto e.One DAC3, which he'd reviewed in the November 2007 Stereophile.

I added the e.One DAC3 to the system, connecting its single-ended outputs to the Krell Evolution 202's S2 input via a 1m run of Shunyata Research Altair interconnects identical to those I was using with the MS750. I connected the MS750's digital output to the Bel Canto's BNC connector with a short run of Stereovox VX2 digital interconnect. Then I powered everything up and let it settle for 12 hours or so, having read in the Bel Canto's owner's manual that it would sound best after 48–72 hours of warmup.

Naturally, I was in too much of a hurry to wait that long, so bright and early the next morning I began comparing the two in level-matched auditions. At first, I was impressed by how strikingly similar they sounded. But as time went on—and as, I presume, the DAC3's circuits settled down—this changed. Increasingly, I heard the Bel Canto as more articulate, clean, and quiet. I could hear more of the acoustic, especially in recordings such as the Tallis Scholars' performance of Tompkins' Third Service (Gimell 54294). Switching back to the McIntosh made individual voices sound less distinct from each other, and lost much of the precision of attack that distinguishes the Scholars from lesser choirs.

I went back and listened to the first recordings I'd compared: Acoustic Guitars' Gajos in Disguise (STUCD 19001) and Chanticleer's A Portrait (Teldec 104743). Sure enough, now it was the differences that were striking. If I auditioned the straight MS750 first, then switched to the e.One DAC3, several layers of fuzz fell away. If I auditioned the Bel Canto first and then switched to the Mac, I wanted to switch back immediately. It wasn't so much the clarity, frequency extension, or depth; it was that the DAC3 compelled me to care about the music, and the MS750 didn't, particularly.

Thinking that it was possible I'd reached my limit of attentive listening and was starting to get cranky, I took a rest. After lunch, I cued up Bennie Wallace's "Sainte Fragile," from Twilight Time (Blue Note CDP 7 46293 2). The Bel Canto caught Wallace's tenor squonk brilliantly. More important, it captured the gutbucket precision of the rhythm section's boogie slop shuffle. When I switched to the Mac, that atomic precision became a lurching stumble.

I couldn't escape the conclusion: by itself, the Mac was a letdown.

Mac factor

I so wanted to become a McIntosh convert. I did find a lot to love about the MS750 and the McIntosh experience. The MS750 was far and away the easiest music server to use that I've incorporated into my system. Its dead-simple user interface should appeal to the computerphobic audiophile, while being sophisticated enough that the computer-savvy can make the MS750 do just about anything they want.

It's true that you pay a premium for that McIntosh faceplate, but you get more with it, too. A three-year warranty, for one thing (the Escient model it's based on comes with only one year). You also get that faceplate, with a larger, easier-to-read alphanumeric display than the Escient's, and that "mission critical" hard drive—not to mention McIntosh's legendary support and resale value.

However, my experiences with the Bel Canto e.One DAC3 make me question the "mission critical" aspect of the McIntosh's D/A conversion—which is, presumably, the part of the MS750 that McIntosh enthusiasts expect to be built "Mac tough."

There are still logical reasons why a consumer might buy a McIntosh MS750, especially if cost is no constraint. In that case, go ahead and get the Mac and the digital processor of your choice. But a little bit of computer savvy, a $300 Slim Devices Squeezebox, and that same processor will get you to the same sonic place for significantly less.

- Log in or register to post comments