| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Conrad-Johnson ART Preamplifier Interview part 2

Phillips: I noticed that balance control is offered only on the remote.

Johnson: We wanted to keep the front panel clean, but we also feel that if you're going to set balance, you want to do it from your listening position anyway. And, of course, the balance function is not an additional control---because the volume control sets each channel's volume separately. There's only one set of switches; what changes are the control instructions. What's interesting is that the microprocessor built into the ART is the same one that used to be in the computers we used to run the business---it's essentially a Z86 with built-in memory, so the program is actually resident on the CPU. Of course, it's a whole lot more computer than we need to turn on and off a handful of switches, but it's a fairly efficient way to do things.

In order to build to the quality level that we insist upon, it is quite expensive to take the approach we've taken in the ART---mainly because we're using Vishay resistors. The cost of the resistors actually becomes an issue. You can buy metal-film resistors for a penny apiece, but we're using bulk metal-foil resistors---which is a metal foil that is trimmed with a laser to create a resistive element---and you're looking at multiple dollars apiece. That adds up pretty quickly when arranging 10 triode sections per channel.

Phillips: How many power supplies are there in the ART---one for each channel, as well as one for the control circuitry?

Johnson: Remember, the control circuitry is nothing but some DC supplies to turn the relays off and on. All the control work, whether we're talking about setting the level or choosing an input, is done with switches. They aren't electronic switches, they aren't FET switches or IC switches, they're relays---mechanical, physical switches---which is why you hear the click, click, click when they're in operation. There are 12 switches in each channel for volume control, and one for each input, and one to mute the output. The computer just decides which switch to throw, and, because they're relays, you have to give them a little DC to open them and close them. But all that's coming off a different transformer and is totally independent of the audio circuitry. Actually, it has to be separate because you need a power supply in order to turn the unit on.

The interesting thing about the audio-circuit power supply is that we don't use feedback there, either. It's a fairly straightforward regulated power supply. A number of people use a feedback supply to get their power-supply regulators, but we just use a direct brute-force approach. The main thing in the power supply is to keep its impedance low. When you're running a signal through the audio circuit, the current you're delivering to the circuit is going up and down with the signal, and the impedance of the power supply will modulate that current. We've designed a power supply with an impedance of a fraction of an ohm in such a way that it maintains that impedance, essentially, across the audio band.

You have to play some tricks to keep that impedance low when you're starting to look at multiple kilohertz. Typically you'd look at DC performance, but our concern is that it have low impedance at high audio frequencies. We've been using this power supply for 20 years---we've refined it over the years, but the basic approach is one we're very familiar with. And because we've used it all that time, we know it's reliable.

Phillips: Is there a feature or function of which you are especially proud?

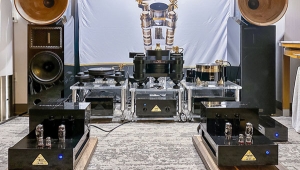

Johnson: Well, it's easy---and pleasant---to use. You don't even have to open the box in order to change the tubes---which is a lesson we learned with the Premier Seven. But ultimately, the whole rationale for the thing is the way it sounds. It is designed to perform at the fringe, to be the state of the art. That's its only reason for being. If you feel the sound is where we feel it is, then you fully appreciate and understand the product. And if you don't, then there's really no excuse for it.

Phillips: How does the ART relate to your future plans at Conrad-Johnson?

Johnson: The most immediate result will be the Premier Sixteen LS [$7995], which is a single-chassis stereo version of the ART. Physically, the product is slightly more than half an ART, which the price reflects. Our big problem was getting it to fit in a single chassis---if you open up an ART, you'll find it's pretty full, it's not just packaged air. So we had to cut back on the number of triodes: There are 12, not 20, and the power supplies are shared across the channels. But that's about it in terms of compromise.

It's going to be a very interesting product---I think it's going to come very close to the performance of the ART. But I don't see any practical means of trickling it down to the next step. The costs involved just remain too high for us to produce this design for as little as we'd like to.

- Log in or register to post comments