| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I don't even understand what "composition" in modern jazz means; something like "plot" in a documentary I guess.

There is a counterargument. It goes like this: Jazz today is vital and dynamic because great players keep popping up, all over the world. Very few of those great players are also great composers. Yet they apparently feel obliged to be. A large proportion of new jazz albums contain all or mostly originals.

Economic incentives are in play. Original compositions possess the potential to generate royalties, in addition to the payment for performance. Conversely, if you record music written by others ("covers"), it may be necessary for the performer to pay royalties. But money alone does not fully explain this fixation on original material. The proliferation of academic jazz programs may be a factor. A young musician who got an A in composition class might be forgiven for assuming that she is a composer. Current jazz musicians seem to think that to be taken seriously, they must compose. That perceived obligation can be a curse.

Original composition has always been an essential element of jazz, and there are some excellent composers on today's jazz scene. What is new is the presumption that to play a cover is to compromise. Back in the day (ie, in the 20th century), more value was placed on creative interpretation. Jazz musicians commonly used sources like American Songbook standards, classical pieces, pop and country tunes, and folk music as settings for improvisation.

Today, much great music from the vast archives of our shared human heritage is in danger of lying fallow. Many of today's jazz albums would be better if their program material were more interesting. There are too few jazz musicians like pianist Bill Charlap, who is willing to say, "I love the songwriters. I'm not a composer. My calling is to be an improvising jazz musician, interacting with other musicians, staying extemporaneous all the time."

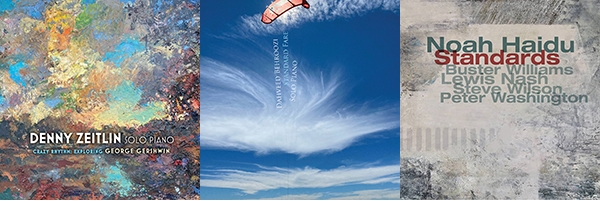

Into jazz's present vigorous but self-limiting moment, three new CDs arrive like a blast of fresh air, all on the Sunnyside label, by Denny Zeitlin, Dahveed Behroozi, and Noah Haidu. They are all fascinating, dissimilar pianists. They all compose, but each has just released a standards album. They all know that certain kinds of inspiration only happen for them when they improvise on great songs that are deeply embedded in their collective tribal language.

Zeitlin, at 85, still works three jobs: college professor; clinical psychiatrist; A-list jazz pianist. An ongoing commitment in his busy and productive life has been an annual solo concert at the Piedmont Piano Company in Oakland, California, featuring the work of a single composer. Crazy Rhythm: Exploring George Gershwin (Sunnyside SSC 1693) contains some of the most familiar songs in American musical history, but you have never heard them like this. "Summertime" has a brand-new prologue, which surges and swells. When the immortal melody finally rings out, it is a rush.

For Zeitlin, it was not a night for intimate understatement or wistful reflection. Normally graceful songs like "It Ain't Necessarily So" take on sharp angles and hard edges. Often, his powerful left hand marks out a grid of thick lines within which his right hand roams free. Gershwin's keys and harmonies become provisional. "My Man's Gone Now" is a ballad in tempo but not in tone; Zeitlin turns it into a series of dark, dramatic pronouncements. Over 13 minutes, he wrings the song dry.

Dahveed Behroozi is a gifted, fearless improviser who shares with Zeitlin a faith that standard repertoire can be a prism for creative refraction that is otherwise unachievable, that can provide otherwise unreachable epiphanies of cultural resonance. Standard Fare (Sunnyside SSC 1689) is his third album and his first solo album. Behroozi ventures even further from his sources than Zeitlin does. On "All the Things You Are," he apparently is thinking of Kern and Hammerstein's form but rarely of their melody. His outpourings only tease and hint at the song. But for him, as for Zeitlin, well-known themes become threads, touchpoints that recur and unify far-reaching improvisations. When Behroozi plays "The Nearness of You," Hoagy Carmichael's song emerges frequently like intermittent flashes of light. But he pauses in places Carmichael didn't, because the melody triggers emotional associations that overtake him. "The Nearness of You" becomes Behroozi's own story.

Noah Haidu's trio album Standards (Sunnyside SSC 1706) is the most conservative work of these three. Haidu operates within the envelope of a well-defined tradition. (Keith Jarrett's Standards Trio is his paradigm.) His taste, musicianship, and sheer pianistic elegance make him so trustworthy that you just relax and let Standards wash over you. Tunes like "Just in Time" and "I Thought About You" glide with a grace that feels effortless. Haidu gravitates naturally toward ballads. He proceeds patiently, even hesitantly, through "All the Way" and "Skylark," carefully bringing previously submerged feelings to the surface.

These three albums demonstrate that in jazz, interpretation is as fine and deep and necessary an art as composition.

I don't even understand what "composition" in modern jazz means; something like "plot" in a documentary I guess.

It means the same thing it means anywhere else -- new melodies, rhythms, and harmonies. What's not to understand? And a piece that seems to discourage new composition in jazz seems very odd to me. It seems like just what jazz needs, not more rehashing of old compositions.