| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Rabbit Holes #4: Elvis On Tour

FLASH! Record Business Conquers Death! Musicians Live Forever! There is life after death in the world of recorded music. Elvis left the building 46 years ago. Jimi Hendrix has been absent for 53 years. Yet both continue to release albums of unreleased material. Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and Bruce Springsteen wisely recorded much of their music throughout their careers, live and in the studio; they'll continue to release "new" music long after they pass.

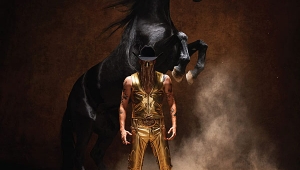

Keeping fans satisfied but also looking forward is an effective marketing tool, one that Ernst Mikael Jørgensen, the guru of all things Elvis, has mastered. His latest project is the six-CD box set Elvis On Tour, which is connected to the 50th anniversary of Presley's 1972 US tour and the rerelease of the MGM documentary/concert film of the same name, a Blu-ray of which is also included.

Apart from the movie, this set's selling point is 91 unreleased tracks of Presley performing in small-market cities: Richmond and Hampton Roads, Virginia; Greensboro, North Carolina; San Antonio, Texas—and rehearsing at RCA Studios in Hollywood. Each venue gets its own disc, with two discs of rehearsals.

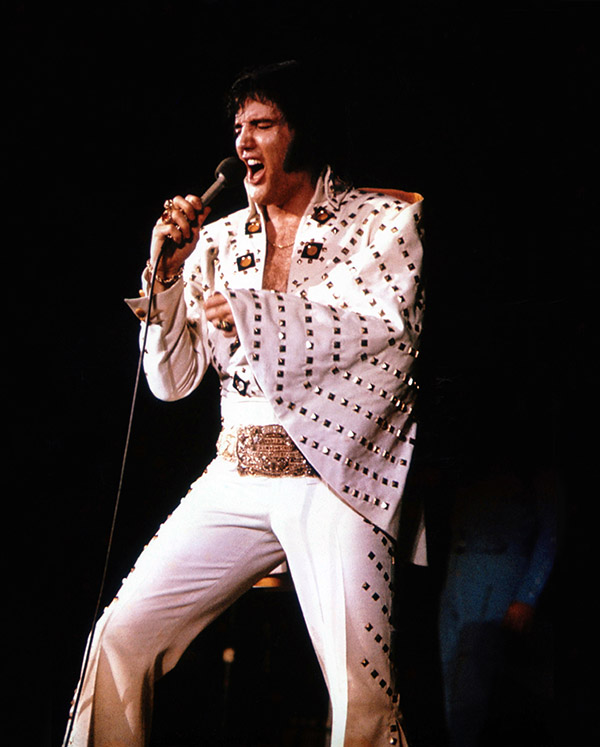

Elvis sounds relaxed and committed. His band is the embodiment of both musical and professional excellence, filled with incomparable talents like James Burton (guitar), Ronnie Tutt (drums), and Glen D. Hardin (piano). But, while these performances have an energetic charm, it's striking that, in a year widely considered to be the best ever for landmark rock-album releases (Harvest, Exile on Main Street, Ziggy Stardust), Elvis, who often lamented not becoming the artist he wanted to be, was enthusiastically reprising old hits, pop numbers, and spectacles like "An American Trilogy."

Photo by Steve Barile

The engineer on Elvis releases since 2016 is Matt Ross-Spang, a young, talented, much-in-demand producer/engineer who grew up in Memphis and began his career at Sun Studios. Ross-Spang has worked on projects by the Drive-By Truckers, St. Paul & The Broken Bones, and Margo Price. He engineered John Prine's final album, The Tree of Forgiveness, and took part in two Grammy-winning albums by Jason Isbell. In an interview with Stereophile, he let out a knowing chuckle before saying that engineering and especially remixing Elvis tapes was something very different.

"The 2" 16-track tapes are barcoded, and all the multitracks are handled with white gloves and treated like the Ark of the Covenant. They've been digitized pristinely, mostly at 192/24. Ernst knows the catalog like no one else, not just in an archival way but in an emotional, technical, and spiritual way.

"When they recorded Elvis live, they had at least two machines going. Running at 15ips, which is basically a medium speed. You have about 33 minutes on each tape, which isn't enough for a full concert. That means you must have two machines going that cross each other, so when the first machine runs out, the B machine is going, and you can thread up the new one. So, there's a master and a safety for each song," he explained. "Often, I have a picture of the original reel-to-reel tape box. And sometimes the engineer would leave notes, like maybe EQ, panning, that kind of stuff. I re-edit the transfers to match the original concert. I have to redo all the tape splices, see which machine sounds better, and put those together and get it back to what they originally had to mix from. Then I start remixing. I basically edit the whole show as one long song."

"It's not a static mix," he continues. "Everything kind of rides like a wave through the record. I have the benefit of not working on tape. I can play something over and over and not worry about it getting noisier. And I can use more surgical EQ than they could have, to get out any feedback; in Elvis's mikes, especially, you hear a lot. In one of the versions of 'Can't Help Falling in Love,' you hear a lot of girls smooching on him as he makes his way through the audience. Elvis liked to wear a lot of rings, and those rings clack on the microphone, so I can take some of that out."

Originally recorded by Wally Heider's mobile recording unit, one track, "I Got a Woman" from the Hampton Roads show, had a problem with the channel recording Elvis's vocal. And in an odd bit of copy-editing, drummer Tutt is left out of the credits listed in the booklet, but Ross-Spang assured me that it is indeed Tutt in all shows.

While still much louder than it needs to be, the sound of the unreleased live shows is remarkably full and balanced. Ross-Spang said that while "stylized" and in spots even lightly compressed, his mixes stay true to the originals and don't add anything modern like drum samples. They accurately capture the sweep of the arrangements, which, as Baz Luhrmann's recent film Elvis conveys in one telling scene, Elvis wanted big and dramatic.

It's a style that Ross-Spang has come to appreciate after hours of listening. "Pop music used to be these big, orchestrated arrangements and now it's often a looped sampled drum, a vocal, and a simple keyboard part. Going back and hearing 'Never Been to Spain,' even the orchestration and arrangement on 'An American Trilogy,' and how so many of those Elvis songs start with just a light piano and a little drum, and then the choruses ramp in with background vocals, strings, and horns—they all make you feel something. These bold cinematic arrangements have really inspired me in my recording and production, to try and find some of those moments."

- Log in or register to post comments