| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

for $110 /m these give you a lot of bang for your buck

The song takes its name from the Los Angeles studio in which it was recorded, formerly known as Marvin Gaye Studios and founded by Gaye in 1975. According to Tom Kenny, editorial director of Mix magazine, Marvin Gaye Studios was "the Studio 54 of the West Coast"—the venue for legendary parties where athletes, politicians, movie stars, models, and musicians mingled and cavorted, supposedly for days at a time. It was Gaye's AIR, his Sun, his Electric Lady, his second home. Perhaps his first. In the late 1970s, when Gaye's financial troubles resulted in the studio's foreclosure, he was crestfallen. Kenny cites Gaye's former wife, Janis: "He went into a deep depression. The enormity of losing his studio was so devastating to him that he was never the same after that. We had gone bankrupt, lost our home, our cars—everything. But he was a broken man over the studio. . . ."

In the late 1980s, Marvin Gaye Studios became a temporary site for Eldorado Recording Studios, but the new facility held little connection to its previous owner or those carefree parties of the mid-'70s. When Eldorado found a permanent location in Burbank in 1996, it looked as if any physical connection to Gaye's vision and work would be lost altogether. But in a surprising twist, just as the old studio was to be converted into a digital photo lab, it was purchased by record-label executive John McClain, renovated to honor the late soul singer, and given a new name: Marvin's Room.

With all this in mind, I can't help wondering if Drake's "Marvins Room" is as much a semifictional account of Gaye's personal troubles as it is a semiautobiographical version of Drake's own. I Want You, the first album Gaye recorded in his new studio, was released while his romance with young Janis Hunter was in full bloom and his marriage to Anna Gordy was falling apart. I swear you can hear echoes of I Want You in Drake's music. Though the Toronto-based rapper has been disparaged for the low-key, even rueful nature of his work, and has been linked to musical genres, such as emo and goth, that are typically associated with suburban indie artists, I hear a deeper kinship to the "quiet storm" music that Marvin Gaye helped define. Throughout, Take Care is marked by subtle, intelligent rhythmic shifts and a surprising amount of wide-open space. The album is indeed quiet—quieter than most I own, in fact. I like to turn it up loud. The Kimber PBJ interconnects do an outstanding job of re-creating the performance space, setting well-defined musical images within a surprisingly wide, deep soundstage.

Producer Noah Shebib's inventive use of electronics, live instruments, and real dynamic range combine with Drake's impressive knack for moving easily between sung and rapped verses to make "Marvins Room" a sonic and musical success. With a flurry of staccato syllables and melodic twists, Drake's character describes the events that led to his making a late-night phone call to a former lover. I'd like to cite a few lines from the song, but because even I can't bring myself to use such caustic language in the hallowed pages of Stereophile, I'll paraphrase: "I think I'm addicted to naked pictures and sitting, talking about [women] that we almost had / I don't think I'm conscious of making monsters out of the women I sponsor until it all goes bad." A psychotherapist would have a field day with such confessions.

The young man knows very well that his ex is happily involved with someone else, but he nevertheless attempts to regain her love. Again, I paraphrase: "[Forget] that [worthless new guy] that you love so bad / I know you still think about the times we had."

Never mind that Drake twice end-rhymes had with bad; his steady flow and fine use of internal rhyme get him off the hook. Alongside a heavy kick-drum beat and through some clever production work, we hear samples of a phone conversation: "It's Friday night, I'm mixed up / I've been talking crazy, girl / I'm lucky that you picked up, lucky that you stayed on / I need someone to put this weight on." Shades of Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being?

The female character, clearly annoyed but not without some lingering affection, asks, "Are you drunk right now?"

To anyone familiar with alcohol addiction, the question is a familiar one; the answer, of course, is yes. The young man apologizes for calling, but not without adding a barb: "I'm just saying you can do better."

This is fairly heavy, strangely earnest content for a pop song, especially one in the hip-hop genre. Drake is playing with sentimentality, working on our more vulnerable emotions. For me, at least, it works: I feel a connection to his character.

I liked "Marvins Room" a lot before adding Kimber Kable's PBJ interconnects to my system. Now that they've been in for a few weeks, I feel obliged to share these thoughts with you. A part of me worries that some readers will expect an apology—John Marks gives you Delius, I give you Drake—but I think there's something to be gained from all this: If you, like my dear Uncle Omar, still insist on using cheap, no-name cables in your hi-fi, well, I'm just saying you can do better.

Things that last

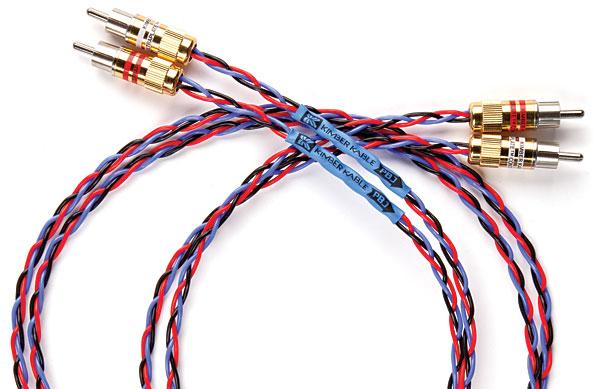

Kimble Kable's PBJ interconnect was deleted from our "Recommended Components" list in April 2005, but only because too much time had passed since we'd last heard it to be sure that it still belonged there. Corey Greenberg reviewed the PBJ in July 1993, when I was 16 and still listening to music, almost exclusively rap, through a small GPX boom box: some of my favorite groups were Black Sheep, A Tribe Called Quest, Lords of the Underground, and Leaders of the New School. Corey was probably listening to Nirvana through his He-Man rig. The PBJ then sold for $62/1m pair, which translates to about $98 in 2012. According to Kimber Kable's founder, Ray Kimber, today's PBJ is almost identical to the interconnect he originally released in the late 1980s (footnote 1). At the time, he wanted to make a minimalist cable, using only materials he had on hand. The recipe is simple: "Take three high-quality multi-strand wires in individual Teflon jackets and braid together. We have refined connectors and materials over the years, but even a decades-old PBJ should still make music."

I love things that last, and the small increase in price, to $110/1m pair, seems fair to me. The fact that Kimber's tried-and-true PBJ—not the Mk.II or v.6 or Special Edition PBJ, but the same old design—has stuck around this increasingly fickle world all this time is just one reason to take notice.

for $110 /m these give you a lot of bang for your buck