| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

The Fifth Element #62

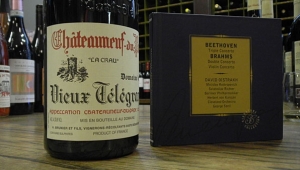

Vivid speakers change the game. But first a great piano recording: Tributaries: Reflections on Tommy Flanagan (CD, IPO IPOC1004), from the late Sir Roland Hanna (his title was an honorary knighthood granted by Liberia). I missed this wonderfully crafted solo-piano recording when it first came out in 2003, and still would not have known about it today except that a publicist sent me an e-mail saying that he was cleaning out his shelves of leftover promotional copies. I quickly sent back a request, in large part because one of my Desert Island recordings is Jim Hall's Concierto, originally released in 1975 on the CTI label, and on which Hanna had played. Concierto has since been reissued in digital form many times, most successfully, as far as I can tell, by Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab on an SACD (UDSACD 2012) that includes new tracks, as well as alternate takes of tunes on the original release.

Footnote 1: My extremely brief personal association with Tommy Flanagan was entirely serendipitous. To promote new releases on my label, John Marks Records, at Stereophile's 1996 High-End Hi-Fi Show, at the Waldorf=Astoria in Manhattan, I arranged with loudspeaker manufacturer ESP to hold in their exhibit rooms a "Music Minus One" live demonstration and press reception. The plan was to present the demonstration for invited members of the press, then drink some champagne and decompress. Stereophile writer Lonnie Brownell asked me whether he could bring a couple of non-journalist friends. I imagine my eyes grew quite a bit larger when Lonnie's friends turned out to be Tommy Flanagan and drummer Max Roach. They arrived early, and charmingly ignored my tongue-tied-ness. After the music was over, I told them to stay seated. I zipped into the adjoining room, grabbed two glasses of champagne off a waiter's tray, then handed them to Flanagan and Roach. A priceless memory.

I do wish, however, that remastering producers and engineers would show a little more respect for the artistic integrity of the original release by leaving a long silence between the end of the original program and the start of the extras. On the MoFi SACD there's a gap of only about a second between the end of the heart of the album, Don Sebesky's arrangement of the slow movement of Rodrigo's Guitar Concerto, and the uptempo Duke Ellington tune ("Rock Skippin'") that is the first additional track. It seems no one remembers sitting breathlessly by the turntable in the 1970s as the music died out, and then—silence.

I do wish, however, that remastering producers and engineers would show a little more respect for the artistic integrity of the original release by leaving a long silence between the end of the original program and the start of the extras. On the MoFi SACD there's a gap of only about a second between the end of the heart of the album, Don Sebesky's arrangement of the slow movement of Rodrigo's Guitar Concerto, and the uptempo Duke Ellington tune ("Rock Skippin'") that is the first additional track. It seems no one remembers sitting breathlessly by the turntable in the 1970s as the music died out, and then—silence.

This reissue is not the only offender. The extra material on the digital reissues of Miles Davis' Kind of Blue also crowds in on the original tracks, especially as that is a take recorded earlier than the one chosen for the original release; the extra material is, in a way, a step back, in chronology if not in quality. It should occupy more of a space of its own.

A counter-example: When Bob Ludwig mastered my recording of Arturo Delmoni and Yuri Funahashi performing violin and piano sonatas by Brahms and Amy Beach (CD, John Marks JMR 2), Arturo and I could not agree on the playing order. I thought that his and Yuri's performance of the end of Brahms' Sonata 1 was so poetic that nothing should follow it. Arturo, however, thought that the better-known piece should go first. I came up with the idea of adding dead air to the end of the final movement of the Brahms—if I recall correctly, at least 16 and perhaps as many as 20 seconds, except that I was timing by musical beats, not the clock. We tried it, it worked.

One of the highlights—and the actual musical climax—of Concierto is Roland Hanna's piano solo, wherein the climactic modulation really sounds like an emotional breakthrough. Concierto is the pick of the CTI litter, and you really should have it. The regular CD costs $6.99 from Amazon.com, and there are many copies on the used market, including regular and 180gm LPs.

Back to Tributaries. I was favorably disposed to the album even before I received it, owing to its connection to Concierto. I was even more favorably disposed when I began to play it. The album was recorded at the Performing Arts Center of SUNY Purchase, New York, a noted classical venue where one of my own recordings, cellist Nathaniel Rosen's Reverie, was also taped. Tributaries' engineer was Tim Martyn, a noted classical recordist who has worked with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and the London Mozart Players. The sound is first-rate, although this is not a recording with the usual distant "classical" perspective. The sound is crisp and clear, with powerful bass, but no intrusive action sounds.

As its subtitle makes clear, Tributaries is Hanna's tribute to Tommy Flanagan, who had been his friend since boyhood in Detroit, which in the 1940s and '50s was a much more important jazz town than it is now. Of the 11 pieces on the recording, only two, "Sea Changes" and "Delarna," were written by Flanagan, though the rest—ranging from Thad Jones' "A Child Is Born" to Green and Heyman's "Body and Soul" to the Gershwins' "Soon" (a standout performance)—are all strongly associated with the late pianist (1930–2001).

Though somewhat of a late bloomer, Flanagan did play on John Coltrane's Giant Steps and Sonny Rollins' Saxophone Colossus. He later was Ella Fitzgerald's music director, and did two stints as her pianist. Fitzgerald later said, "He really started getting me singing what I heard inside and what I wanted to get out." It was only in 1978 that Flanagan first formed a trio of his own, the format he stayed with for the rest of his career (footnote 1).

Flanagan's playing was often "classical" in both conception and technique, as was Hanna's. Both sought elegant clarity rather than propulsive power or smoldering intensity. Indeed, the recording for which Flanagan is doubtless most famous, his haunting performance of Horace Silver's "Peace," from his 1978 album Something Borrowed, Something Blue (CD, Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-473-2), is also perhaps the best example of his classical influences.

What's important to note is that Flanagan's "classical" style was fluid, ‡ la Chopin and Debussy, and not monumental, ‡ la Beethoven and Brahms. FM-radio listeners throughout New England had Flanagan's rendition of "Peace" engraved on their hearts because for many years it was the opening theme of Eric in the Evening, Eric Jackson's evening jazz program on WGBH-FM.

Footnote 1: My extremely brief personal association with Tommy Flanagan was entirely serendipitous. To promote new releases on my label, John Marks Records, at Stereophile's 1996 High-End Hi-Fi Show, at the Waldorf=Astoria in Manhattan, I arranged with loudspeaker manufacturer ESP to hold in their exhibit rooms a "Music Minus One" live demonstration and press reception. The plan was to present the demonstration for invited members of the press, then drink some champagne and decompress. Stereophile writer Lonnie Brownell asked me whether he could bring a couple of non-journalist friends. I imagine my eyes grew quite a bit larger when Lonnie's friends turned out to be Tommy Flanagan and drummer Max Roach. They arrived early, and charmingly ignored my tongue-tied-ness. After the music was over, I told them to stay seated. I zipped into the adjoining room, grabbed two glasses of champagne off a waiter's tray, then handed them to Flanagan and Roach. A priceless memory.

- Log in or register to post comments