| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

The Fifth Element #43

My "Musical Cultural Literacy for Americans" write-in competition seems to have been a smashing success. I received 65 entries, and only a very few missed the mark. A few more were obvious, so-so, or lacking in passion. Many were good. But a score or more were of enviably high quality. Choosing the top 12 was tough. At the end, who won a prize and who did not was entirely my own subjective decision. The winning entries are posted in full on Stereophile's website as an appendix to my April column. Here are the points I made online in announcing the results:

Footnote 1: I was flabbergasted by that Simpsons episode. The only conclusions I could come to were either that the producers of that program were incapable of holding anything sacred, or that younger generations having gotten a little tired of how old folks mythologize people, places, and things, regard JFK as just another feckless politician, remarkable not for anything he did in office but only for having bonked Marilyn Monroe. And I'm not sure that that is entirely a bad thing for the Republic.

"Here's an idea: instead of spending $100 on new pucks, cones, mats, wires, or tubes, how about spending $100 on randomly selected recordings from these lists that are unfamiliar to you? You might be able to pick up quite a few on eBay for comparative peanuts.

"Worst case, you may decide you will never listen to something again. If that happens, you can donate it to your local public library and claim a charitable deduction. (If spending $100 is not within your comfort zone, just borrow recordings two or three at a time from your public library, listen intently, and add titles to your wish list.)"

Now that the dust has settled, perhaps a few more words about cultural literacy are in order. One of the foundational notions of cultural literacy is that it constitute familiarity with the body of knowledge and works of art that today's "content creators" (I hate academic jargon, but sometimes it's the only thing that does the job) will assume their audience is familiar with. Of course, there is an element of circularity in that definition.

To give a silly example, in one episode of The Simpsons, some organized-crime types shoot at Homer Simpson from behind a picket fence. As they flee the scene, one says to the other, "I told you we should have brought more than three bullets." Obviously, the person who wrote that episode assumed that his audience would be familiar not only with the assassination of John F. Kennedy, but also with conspiracy theories that regard the official Warren Commission report as a cover-up, or the product of dupes (footnote 1).

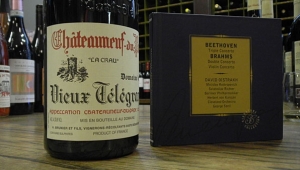

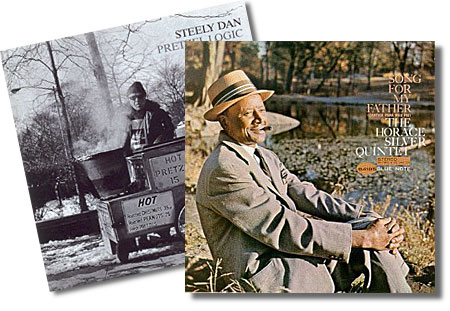

In much the same way, when rappers Lord Tariq and Peter Gunz borrowed the bass line (and a synth lick) from Steely Dan's "Black Cow" (from Aja), Tariq and Gunz doubtless assumed that at least their peers (if perhaps not their audience) would get the reference (footnote 2). (Extra-credit essay question: Is the bass line to "Rikki Don't Lose That Number" Becker and Fagan's homage to A Love Supreme's "Acknowledgement"?)

So, in separating the great lists from the good lists, I tended to favor the body of works that today's content creators will assume familiarity with, rather than works by today's content creators. A few specifics: I considered and ultimately rejected including some brass or military band music (such as John Philip Sousa's) in my own list. While brass-band music was extremely popular in the 19th century (at the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries, there were perhaps as many as 30,000 brass bands in the US), I am unpersuaded that today's content creators assume familiarity with the genre. But I may be wrong. Quite a few respondents felt passionately about the issue, so I let them have their say.

Stephen Foster: Good catch. No Stephen Foster, no Gordon Lightfoot, James Taylor, and all the rest of that ilk.

Dvorák: Right-o. Enough said. By the way, I think John Williams slipped a reference to Dvorák's Symphony 9, "From the New World," into his score for Close Encounters of the Third Kind, when the alien mothership blasts bass notes at the contact site. Either that, or that's a self-quote from the Jaws theme.

John Williams: Again, I don't know how much his work shows up in other works, but, certainly, a huge cultural presence. Williams' film scores are probably as close to classical music as a lot of people today ever get. Good catch.

Other good catches: Gospel music, Alan Hovhannes' orchestral works, Little Feat's Waiting for Columbus, the Allman Brothers, Janis Joplin, Sarah Vaughn, Errol Garner, Nancy Wilson and Cannonball Adderley, George Benson, Keith Jarrett, Rebecca Pidgeon, Meat Loaf, Brian Eno, the Monkees, the Grateful Dead, Native American music, and Hawaiian music.

Thanks again to all who entered. Congratulations to the winners—their lists are well worth printing out or saving as shopping lists. This was so successful that perhaps—perhaps—by year's end we can do it again in a slightly different format, this time for the Western Classical canon. Stay tuned.

American Idol

As long as I'm tying up loose ends, I'll comment on the mind-boggling fact that Melinda Doolittle was thrown off American Idol while Blake Lewis remained. (Of course, by now, we all know that effervescent, personable, and precocious Jordin Sparks is the new Idol. Don't we? Criminy, I sure hope so!)

I have seen it asserted that there is fine print extant in which the producers of the show note that they are guided but not bound by the vote totals, although I hasten to add that I have not seen this myself. So either the producers thought that having an African-American woman and a biracial woman (both of whom deserved to win) face off in the final round would cost them viewers, or the demographics of the population that votes is radically skewed in favor of white teenage girls 16 and under, and that subset bloc-voted for Lewis. Lewis is innocuous and entertaining, but his singing is totally undistinguished. His claim to fame is making explosive rhythmic noises with his mouth. All fine and good, but it's not singing.

If, by this time, you've decided that I've taken leave of my senses, please bear with me. I had never paid that much attention to the show before this season. It seemed to offer a choice among "sensitive" men, ersatz cornpone, and Stepford Sopranos. However, when I lucked into hearing Melinda Doolittle sing Lorenz Hart's and Richard Rodgers' (not Chet Baker's, as some sources claim) "My Funny Valentine," I was not only hooked, I was voting. I tell people that Doolittle appears to be every pastor's dream youth-group leader. Indeed, she is an alumna of Belmont College in Nashville, a fine music school whose visiting-artist series afforded me opportunities to hear some world-class music during my Nashville days.

Melinda Doolittle has the makings of a first-class interpreter of the Great American Songbook. If you doubt me, just go to www.youtube.com and search for Melinda Doolittle + My Funny Valentine. It's all there: pitch security, tone color, phrase-shaping, intelligence, emotional resonance, joie de vivre, and style—genuine style, not clacking around in mommy's high heels. What a gift. So now I have to go online and buy a "DON'T BLAME ME, I VOTED FOR DOOLITTLE" bumper sticker.

Why don't we all pool our funds and get Melinda Doolittle into a quiet but acoustically live space with an orchestra, some old ribbon microphones, 30ips two-channel analog tape, and a stack of pre-1960 sheet music? To quote another from the Great American Songbook, "I can dream, can't I?"

Footnote 1: I was flabbergasted by that Simpsons episode. The only conclusions I could come to were either that the producers of that program were incapable of holding anything sacred, or that younger generations having gotten a little tired of how old folks mythologize people, places, and things, regard JFK as just another feckless politician, remarkable not for anything he did in office but only for having bonked Marilyn Monroe. And I'm not sure that that is entirely a bad thing for the Republic.

Footnote 2: The pseudonym Peter Gunz itself puns on the 1958–61 private-eye television show Peter Gunn, which was the first US network series to feature jazz regularly, not only as theme music but also as location music—Gunn's girlfriend was a nightclub jazz singer. Henry Mancini's two RCA Living Stereo albums of music from the series were major critical and sales successes of the early stereo LP era. (Although I seem to remember a box of 45rpm discs.) And just because you always want one more trivia bit: Future film composer John Williams was a member of Mancini's orchestra at the time. One more? Victor Feldman played vibes on the More Music from Peter Gunn LP (and may have played without liner credit on the first project). Feldman later played on and composed for Miles Davis' Seven Steps to Heaven, and later still played percussion, keyboards, and vibes on several Steely Dan records, including Aja. Full circle!

- Log in or register to post comments