| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Recording of February 2008: White Chalk

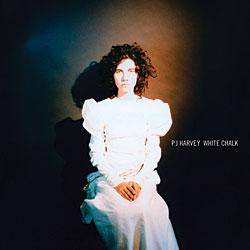

PJ HARVEY: White Chalk

Island B0009972-02 (CD). 2007. PJ Harvey, John Parish, prods., mix; Flood, prod., eng., mix. ADD? TT: 33:34

Performance *****

Sonics ***1/2

White Chalk contains no trace of the blues-drenched rock of Polly Jean Harvey's first four astonishing albums, or the lean, restrained, almost dignified (in comparison) pop of the three that followed—which, for all their taste and craft, somehow never sounded as necessary as Dry, Rid of Me, 4-Track Demos, and To Bring You My Love. Instead, with her eighth album, PJ Harvey has started over. Which is not to say that White Chalk is a return to form. Instead, it's a break with anything and everything Harvey has ever done.

The photos on the cover and inner sleeve (the CD is packaged like an LP: no jewelbox) show an expressionless Harvey face-on and in profile in a plain white ankle-length Edwardian dress with puff sleeves. The effect—of a mug shot taken in 1910 of an inmate of an insane asylum—is entirely in keeping with the music. Imagine a young woman of a century ago, betrayed in love, heart and mind broken, locked in an attic full of damaged or out-of-tune parlor instruments, and forgotten by her embarrassed family, who speak of her as dead when they speak of her at all.

The photos on the cover and inner sleeve (the CD is packaged like an LP: no jewelbox) show an expressionless Harvey face-on and in profile in a plain white ankle-length Edwardian dress with puff sleeves. The effect—of a mug shot taken in 1910 of an inmate of an insane asylum—is entirely in keeping with the music. Imagine a young woman of a century ago, betrayed in love, heart and mind broken, locked in an attic full of damaged or out-of-tune parlor instruments, and forgotten by her embarrassed family, who speak of her as dead when they speak of her at all.

On the evidence here, the feeling is mutual. In one after another of these brief fragments, Harvey sings directly to mummy, daddy, lover, child—but whether this is the voice of a lone survivor singing to ghosts, or of a ghost singing to the forgetful living, is unclear. In fact, much remains unclear even after several hearings. But the indecipherability of many of Harvey's words makes those that can be understood all the more striking.

In "Dear Darkness," a delicate waltz about a double suicide, two lovers (the other voice is that of John Parish) coax and gently remonstrate Death to fulfill his obligations: "Dear Darkness, now's your time to look after us / Because we kept your clothes, we kept your business / When everyone else was having good luck." The singers seem to smile; Death's tardiness, it seems, will be forgiven.

The album's pervading atmosphere of fragile dread is built of small moments. In "Grow Grow Grow," what sounds like an obsessed child kneels staring down at the ground, in which she's just planted . . . something. Her chant of "Grow Grow Grow" becomes a threat, then a demented wail. As for what she's planted, it probably wasn't a seed.

Most striking, and alone worth the purchase price, is "When Under Ether," whose deadpan presentation of an almost beatific peace experienced during an abortion is a masterpiece of tonal and musical ambiguity as precise as it is noncommittal: "I lie on the bed, waist-down undressed / Look up at the ceiling, feeling happiness / The woman beside me is holding my hand / I point to the ceiling, she smiles so kind / Something inside me, unborn and unblessed / Disappears in the ether, this world to the next." Each couplet is followed by the refrain: "Human kindness." The words mean exactly what they say, or their opposite, or both. I hear no trace of irony, and my desire to hear more of this story is perfectly balanced by my relief that Harvey stops when she does—an almost textbook example of creative tension. What is absolutely clear is that, once heard, this song is not forgotten.

These 11 songs total barely half an hour; most end before the chorus can be sung a second time. Only "The Devil," "The Piano," and "Silence"—which gets the loudest, fullest arrangement—even begin to sound like rock. But nothing here, not even Harvey's vocals, sounds anything like the blues—perhaps the bravest or most foolish artistic choice possible for someone who, on the strength of her first four records, is one of the greatest blues singers of all time. Here, Harvey sings like a wraith or waif or both, in a high, thin keen that seems always about to escape her control. She takes artlessness as far as art can take it, and occasionally further.

Each track's arrangement is unique. In "Broken Harp," Harvey accompanies herself on the eponymous antique. Elsewhere are combinations of zither and wine glass, piano and harmonica, occasional vocal processing, and the barest wisps of Mellotron and Mini-Moog. But the overall sonic sensibility is of an acoustic album, each accompanying instrument and minimalist sound carefully chosen for maximum effect. The highs can be harsh, but the mix is clear, deep, and spacious, with—wonder of wonders—genuine dynamic range.

Why put yourself through all this? If the music of PJ Harvey has ever meant anything to you, White Chalk is news. If music is important to you, you may not have known it could make quite this sort of sense. If you have ever experienced or imagined or dreaded the death of a lover, a parent, yourself, or your unborn child, White Chalk can offer an austere but honest peace. I was aware of many different ways that a woman could feel about her aborted child; I was not aware of the one described in "When Under Ether."

For all its power, I doubt that White Chalk points a new direction for Polly Jean Harvey. To go further down this road would, I think, quickly bring her art or psyche, or both, to a point of no return. But for an artist to create, almost sui generis, work of such stark, uncompromised integrity simultaneously draws a line in the sand and erases whatever interior limitations or expectations might have been established by anything that came before. For all their competence and craft, I doubt I'll ever again listen to Harvey's Is This Desire?, Stories from the City, or Uh Huh Her. I may not, in years to come, listen to White Chalk as often as I will to her first four records, but when I do, I know that my attention will be riveted from beginning to end, every time.—Richard Lehnert

- Log in or register to post comments