| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Joint Recording of November 1992: Wagner: Götterdämmerung

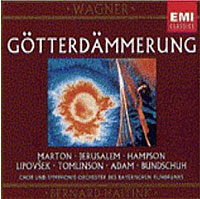

WAGNER: Götterdämmerung

Eva Martón, Brünnhilde; Siegfried Jerusalem, Siegfried; John Tomlinson, Hagen; Thomas Hampson, Gunther; Eva-Maria Bundschuh, Gutrune; Marjana Lipovsek, Waltraute; Theo Adam, Alberich; Jard Van Nes, First Norn; Anne Sofie von Otter, Second Norn; Jean Eaglen, Third Norn; Julie Kaufmann, Woglinde; Silvia Herman, Wellgunde; Christine Hagen, Flosshilde; Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra & Chorus; Bernard Haitink

EMI CDCD 54485 (4 CDs only). Wolfram Graul, Peter Alward, prods.; Martin Wöhr, eng. DDD. TT: 4:17:42

Eva Martón, Brünnhilde; Siegfried Jerusalem, Siegfried; John Tomlinson, Hagen; Thomas Hampson, Gunther; Eva-Maria Bundschuh, Gutrune; Marjana Lipovsek, Waltraute; Theo Adam, Alberich; Jard Van Nes, First Norn; Anne Sofie von Otter, Second Norn; Jean Eaglen, Third Norn; Julie Kaufmann, Woglinde; Silvia Herman, Wellgunde; Christine Hagen, Flosshilde; Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra & Chorus; Bernard Haitink

EMI CDCD 54485 (4 CDs only). Wolfram Graul, Peter Alward, prods.; Martin Wöhr, eng. DDD. TT: 4:17:42

It's easy to get jaded by the constant flood of record-company "product" that monthly drowns my desk: endless, unnecessary recordings of the standard repertoire by no-names with nothing to say.

Well, everyone should have such problems. But as I sat on the edge of my seat for the more than 4¼ exciting hours of this final installment of Haitink's Ring cycle, I felt what I felt when Stereophile first hired me: I couldn't believe I was actually being paid to have such a great time.

Well, everyone should have such problems. But as I sat on the edge of my seat for the more than 4¼ exciting hours of this final installment of Haitink's Ring cycle, I felt what I felt when Stereophile first hired me: I couldn't believe I was actually being paid to have such a great time.

As any critic will tell you, the convincing rave is the hardest sort of review to write—and the past few years' embarrassment of recorded Wagnerian riches has set me to scraping through the bottom of my barrel of superlatives. The two new studio cycles of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, from James Levine (on DG) and Bernard Haitink (EMI), both now complete, have, after not the strongest of starts, moved from strength to strength. With Levine's Siegfried (Vol.15 No.7) and now Haitink's Götterdämmerung, both have ended with recordings that challenge the best of the last 40 years.

In this concluding chapter of his Ring, Bernard Haitink once again proves himself a compellingly dramatic conductor. As much as I enjoyed Haitink's recording of Siegfried (Vol.15 No.3), and Levine's of Götterdämmerung (Vol.15 No.2) even more, and Levine's own Siegfried (Vol.15 No.7) even more than both of those, I have to admit: of the two new Ring cycles, Haitink's Götterdämmerung is the pinnacle in terms of singing, conducting, and recorded sound.

As Levine grew into the cycle, seeming to discover only after recording Rheingold and Walküre that, yes, he did have something to say after all, his vision grew ever more grand, noble, and expansive. His own Götterdämmerung was very nearly profound, his Siegfried darker, more foreboding than any other. Levine's is definitely a god-driven Ring, vast elemental forces passing shuddering through his monumental world-orchestra. His darkly elegiac grandiloquence in the Ring's last half almost makes up for his cold, lumbering emptiness in the first.

Haitink's approach has been quite different, and—considering his reputation of careful, balanced scholarship and impeccably "correct" if unexciting performances of the standard symphonic repertoire—all the more surprising. For Haitink has, from the beginning (Die Walküre, Vol.13 No.4), been far more interested in the tale, in character and motive (this last in the senses of both Wagner and Stanislavsky), in real people and their problems.

This Götterdämmerung is a triumph of that approach. Everything I've always read about Furtwängler's vision of the Ring, but in his two extant recordings have never actually heard (a generational glitch?), I now hear in Haitink: that seemingly instinctive feel for the act-long line and rhythm of this architectonically most challenging of works, that sense of (quite literally) divinely inevitable unfolding, of a door opening upon a musical/dramatic tale ever and already in progress. Haitink shows no hesitation (as did Karajan for DG), nor does he drive the music past itself (as so many accuse Solti of doing); nothing here is rote (like Janowski), or a primer in some revisionist conductoral manifesto (Boulez). Haitink is spiritual without being too reverent (like Goodall) or remote (like much of Levine), and lean without Krauss's tendency toward scrawniness. In fact, and despite its entirely different tonality and pace, I find Haitink's Ring most similar to Böhm's: there is that same strength of pulse and through-line, of a gripping, necessary tale aching to be told, and of a conductor as enabler rather than visionary, window rather than interpreter.

Of course, I know: to make a work sound as if it has not been interpreted is in itself the best sort of interpretation—just as the perfect loudspeaker will sound only "like" whatever music is being played through it. But there can be more than one kind of perfection. Where Böhm's strength was in the effortless Mozartean grace with which he made Wagner's massive orchestrations glitteringly dance without losing a bit of weight or heft, Haitink's is in his impeccably right pacing everywhere, in his superb balance, leading, and accompanying of his singers and orchestra, and in the burnished, polished, golden sound of the Bavarian Radio Symphony. For this is a tonally sumptuous Götterdämmerung for the ages, sounding not at all "digital," but rich, effortless (again!), and—I listened to it in a single 4¼-hour listening session—absolutely unfatiguing.

With very different emphases, I was no less admiring of Levine's Götterdämmerung—until I started talking about the singers. But even here, in this dark age of Wagnerian singing, Haitink's recording—truly a singers' Götterdämmerung—can take its place with the best. The Brünnhilde, Eva Martón, was the single drawback of Haitink's Walküre and Siegfried, but she seems to have got religion for Götterdämmerung. The transformation is astonishing. In the first two operas she seemed to have strength enough only for reining in her large, impressively rich, dark-toned dramatic soprano, leaving nothing whatever left over for nuances of character or emotion. Here, for the first time, she sounds like a fully-rounded person in extreme circumstances, and one who also just happens to be a world-class vocalist. In fact, she turns in one of the most emotionally present, exciting, fire-breathing, strong-willed Götterdämmerung Brünnhildes I've ever heard, even rivaling Nilsson in some scenes. Brünnhilde is a complex character, a demigoddess newly awakened into mortality and swinging from madness to ecstacy to rage several times a day, and Martón is completely convincing. It's hard to believe this is the same singer who somnambulated at full cry through Siegfried. Other than the fact that no one would ever mistake her for a native German speaker, the only drawback is what seems to be a slowly growing wobble. But in a performance this vital, who cares? Even Nilsson had intonation problems.

Martón is almost perfectly matched in Siegfried Jerusalem's Siegfried. Jerusalem seems not to be enjoying himself as much as he did in Siegfried, but here he is in robust, if not exactly finely honed, voice (though he does seem to tire in his Act III retelling of the Forest Bird's advice). He brings an edge to the role that I have not heard before: of a Siegfried in some way aware of his role, if not its ultimate implications, within the curse-tangled universe of the Ring, and on whom the mantle of hero sometimes chafes. Sure, he'll do what's expected of him, but he'd really just rather have a good time. This is a Siegfried as Babbitt, his hail-fellow-well-met beginning to fray around the edges, but who keeps on slapping backs because he doesn't know what else to do; a Siegfried just beginning to wonder why everyone around him isn't having as good a time as he is, when Hagen stabs him in the back. This could all just be a factor of the rough edges of Jerusalem's voice implying a more complex interpretation than the singer intended or was aware of, but it works perfectly, intended or not. For the first time, I was stimulated to imagine Siegfried at 50. Scary.

Perhaps most impressive in this recording, because so unexpected, are the Gibich half-brothers, Gunther and Hagen, sung here by John Tomlinson and none other than Thomas Hampson. Haitink's casting of the latter as the traditionally weak-willed Gunther was a stroke of genius fully equivalent to Solti's choice of Fischer-Dieskau for the role almost 30 years ago: you get a strong singer/actor to play a weak character. Hampson's gorgeous baritone, unique tonal quality, and considerable dramatic range, though not quite as transparently, emotionally accessible as Dieskau's (whose mellifluous croon turned the usually hapless Gunther into a sensitive, reluctant poet-king), still create an interesting, vital character where too often one finds a generic doormat.

And Tomlinson's Hagen is, quite simply, the best since Gottlob Frick's—in some scenes, even better. The voice is big, dark, and serpentinely flexible, and Tomlinson's Calling of the Vassals sounds disturbingly real—this is not pretty to listen to, nor should it be. But listen too to Hagen's short passage in I,i ("Gedenk des Trankes im Schrein"), in which he tells his half-brother and -sister of his idea of drugging Siegfried to forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. In ten short lines he goes from hushed secrecy to quiet triumph to open gloating, Haitink and Tomlinson taking their time to fully experience all of this. It's a small moment, but one thoroughly digested, carefully observed. The entire opera is conducted and sung in this way, Haitink's infectious attentiveness to detail ever in the service of the characters and their inner lives. Listen to Karajan's DG recording for an example of how a dedication equally punctilious but exclusively musical robbed an entire Ring cycle of any life whatsoever, subjecting it to the paralysis of undiluted introspection.

Eva-Maria Bundschuh as Gutrune gives an introspective, matronly reading in a dark, covered voice. She is fully present emotionally, however, as is the very strong Marjana Lipovsek as Waltraute, who reminded me of Christa Ludwig (the best) when she wasn't reminding me of herself; a classic performance. Theo Adam seems to have entirely recovered the singer in his Alberich, which in Rheingold had seemed almost entirely lost. But I've never heard a bad Alberich in this scene; the genius of Wagner's writing seems to make an exciting, committed performance easy, or inevitable, or both.

The three Norns, including as they do some of the better singers of their generation (Van Nes, von Otter), though impervious to technical complaint, are also proof against passion. An argument can be made for this—they are, after all, the Fates, and hardly human—but I think it's a bad one; the one eventuality these particular Fates did not foresee was their own destruction. It should disturb them more than it does here.

The opera's other female trio, the Rhinemaidens, are simply perfect. Anna Russell once called Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Flosshilde "a sort of aquatic Andrews Sisters," and that description was never more apt as here: the voices of Kaufmann, Herman, and Hagen—the first two reprising their Rheingold roles for Haitink—blend so richly and smoothly that it's difficult to believe they weren't all hatched together in the depths of the Rhine. They sing with a flawless balance of clarity and too-good-to-be-true seduction (the Rhinemaidens were, after all, born to entice while themselves feeling nothing but amusement and curiousity), without the almost too-heavy richness of Solti's trio.

Singers, orchestra, conductor, and engineers all come together perfectly in Act II, that miracle of operatic concision and ever-mounting tension, joy and horror, celebration and intrigue, unconscious betrayal and blind revenge. Jerusalem and Martón are savage, drawing blood in their contradictory oaths on Hagen's spear—there is little nobility in them as they spit out charge and countercharge. No, the nobility is all in the orchestra, and lots of it. The Calling of the Vassals is electrifying, gripping as in no other recordings but Solti's and Levine's. I followed the easy-to-read libretto (thanks, EMI) line for line, on the edge of my seat throughout the entirety of this act I've heard a hundred times.

The rest of the opera is no less demanding of the listener's commitment and passion. Haitink gets power, massiveness, and bite from the orchestra in Siegfried's Funeral Music and Rhine Journey, and the Immolation Scene has all the apocalyptically autumnal, dying grandeur it needs. But do be careful when the Rhine overflows its banks to wash away the Gibichung Hall: what the engineers have done here out-Culshaws Culshaw in special effects, and is shockingly appropriate. Owners of WAMMs and IRS Betas might first make out their wills.

The entirely natural, undigital sound throughout all 4¼ hours is that of a real orchestra and singers in the very real—and excellent—Herkulessaal of Munich's Royal Residenz. Though it's hard to believe they avoided it, there's no sonic hint of spotmiking, or of trigger-happy engineers riding gain on four dozen tracks. Perhaps the most satisfyingly, realistically recorded studio Götterdämmerung ever (this is true for the entire cycle), and definitely the best-ever thunder between scenes ii and iii of Act I. Offstage horns (III,i) are handled as well as I've heard, again with no hint of electronic manipulation.

With this Götterdämmerung, Haitink's Ring finally bumps Clemens Krauss's live, mono 1953 Bayreuth recording from my list of Top Three to Recommend. It's almost as accessible as the Solti, though that and the Böhm still have the best singing overall. So Haitink is a very close third choice for singing and conducting, and first choice for sound. But here's a reality check: While listening to this Götterdämmerung, I never once wished I was hearing a different recording, or even thinking that someone else did this bit here better; what little of that there was all came afterward. Haitink's recording is completely satisfying, and that's its glory. If you've never heard the work, it's a perfect first—and last—recording. And that's recommendation enough.—Richard Lehnert

- Log in or register to post comments