| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Recording of January 2006: Wagner: Tristan und Isolde

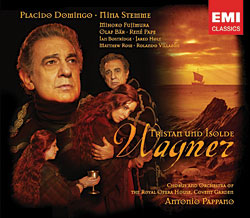

WAGNER: Tristan und Isolde

Plácido Domingo, Tristan; Nina Stemme, Isolde; Mihoko Fujimura, Brangäne; René Pape, Marke; Olaf Bär, Kurwenal; Jared Holt, Melot; Ian Bostridge, Shepherd; Matthew Rose, Steersman; Rolando Villazón, A Young Sailor; Orchestra & Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Antonio Pappano

EMI 5 58006 2 (3 CDs, 1 DVD). 2005. David Groves, prod.; Jonathan Allen, John Dunkerly, Roland Heap, engs. DDD. TT: 3:46:29

Performance *****

Sonics ****½

Plácido Domingo, Tristan; Nina Stemme, Isolde; Mihoko Fujimura, Brangäne; René Pape, Marke; Olaf Bär, Kurwenal; Jared Holt, Melot; Ian Bostridge, Shepherd; Matthew Rose, Steersman; Rolando Villazón, A Young Sailor; Orchestra & Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Antonio Pappano

EMI 5 58006 2 (3 CDs, 1 DVD). 2005. David Groves, prod.; Jonathan Allen, John Dunkerly, Roland Heap, engs. DDD. TT: 3:46:29

Performance *****

Sonics ****½

Richard Wagner long planned but never composed Die Sieger (The Victors), an opera based on the life of Buddha and informed by the writings of Schopenhauer, the closest European thought has ever come to Buddhism. Instead he wrote Tristan und Isolde, perhaps the most persuasive aesthetic evidence we have of the Buddhist principles that human existence is mainly suffering, and that the primary human task is the detachment from the desires that cause such pain.

This is not, apparently, what Wagner thought he was doing. As he wrote to Franz Liszt in December 1854, not long before beginning to compose Tristan, "As I have never in my life tasted the true joy of love, I will raise a monument to this loveliest of all dreams, in which from first to last this love shall for once be satisfied utterly." This from the epicenter of the Romantic movement, of which Wagner was zenith or nadir, depending on one's taste. From the vantage of the psychologically informed if emotionally benumbed 21st century, Wagner seems instead to have, in Tristan, raised to romantic love not so much a monument as a tombstone.

This is not, apparently, what Wagner thought he was doing. As he wrote to Franz Liszt in December 1854, not long before beginning to compose Tristan, "As I have never in my life tasted the true joy of love, I will raise a monument to this loveliest of all dreams, in which from first to last this love shall for once be satisfied utterly." This from the epicenter of the Romantic movement, of which Wagner was zenith or nadir, depending on one's taste. From the vantage of the psychologically informed if emotionally benumbed 21st century, Wagner seems instead to have, in Tristan, raised to romantic love not so much a monument as a tombstone.

While, like Shakespeare, Wagner is never less than deeply compassionate to every one of his characters, to modern ears this opera seems more a scathing critique and condemnation of romantic love. The passion of Tristan and Isolde admits no reality and, famously, no daylight—none of the divisions and boundaries and restraints on which everyday life and any true, mature love must be built. Wagner's "loveliest of all dreams" means misery or death for all whose lives these lovers touch, as well as for the lovers themselves, who remind each other again and again, from Act I through Act III, that they can find true fulfillment only in extinction. Some romance.

It is this latter view that conductor Antonio Pappano and an all-star cast of singers propound in this recording, and it is absolutely convincing. This Tristan is not the hysterical, harrowing, utterly chilling wall of tortured, overwrought, unbridled sound the work so often becomes—and to great power and effect. It is instead a four-dimensional psychomusical drama that, for the first time in my experience, explores in exquisite psychological detail the work's endless shadings of ecstasy, shame, rage, bewilderment, grief, yearning, despair, and guilt. These are the true subjects, it seems to me, of Wagner's most Buddhistic work in a lifetime of creating allegories (such as the Ring cycle) intended to instruct the listener in the pain and suffering that inevitably result from attachment to desire for wealth, power, possessions, immortality, etc. For the first time, this opera sounds not like a pathological passion embodied in sound, but a life-affirming exorcism of that pathology—a catharsis in the Greek sense toward which Wagner always aspired, and which makes him, perhaps, the only true dramatic Classicist among the Romantics.

This catharsis is effected through the minute observation of every musical, emotional, dramatic, and psychological nuance in the score—conductor and singers alike are meticulous about Wagner's dynamic and tempo markings—and it is a testament to the thoroughness of all involved that every role is consummately realized. There is a brief passage in Act I, scene iii in which Brangäne and the orchestra attempt to soothe the despairing, raging Isolde, and the musics of the two women's mental states first overlap uncomfortably, then smooth out into Brangäne's reassurances. The vocal line is fiendishly difficult without at all calling attention to its challenges, and the mezzo, Mihoko Fujimura, makes effortlessly lyrical music of it, serenely sailing these troubled musical waters in a perfect sonic embodiment of what she is trying to do for her mistress. This role has not been sung better, not even by Christa Ludwig. Fujimura's top is so good that she sounds as if she could sing Isolde herself.

Such attention to detail is paid by everyone here—this may be the most thoroughly prepared recording of the work ever made. Though Plácido Domingo has never sung the role in public, he has been studying Tristan for some 30 years. (The first soprano he approached to be the Isolde of his début was Birgit Nilsson, who sadly passed away in January 2006 at the age of 87.) Though his German will never be idiomatic, Domingo's voice, at 65, actually sounds better than ever, and almost entirely leached of any trace of the Italian and French repertoire he specialized in for so long. One indicator of the comprehensiveness and balance of his tone: After a particularly impressive passage in Act I, my wife exclaimed "So dark!" just as I exclaimed "So bright!" We were both right.

Act III is the supreme test of any dramatic tenor—long, exhausting, and exhaustive, a dying man spiritually eviscerating himself before our ears. How to convey this without exhausting oneself and one's audience? Wolfgang Windgassen, that Method singer, wailed and gasped and shouted in agony, and his discipline and musicality made it all work immensely well. Domingo is entirely different but no less powerful in making precise choices of vocal color and volume and phrasing, and it works even better. In a single phrase or note he can reveal Tristan's complex psychology of despair, regret, love, and guilt, his walking wide-eyed into betraying and being betrayed, into death, and he does it over and over again. There is true German style in his singing, every marble note carved with a chisel of hardened steel. This is singing at the highest level, so deeply felt as to be hardly bearable—and it is all in the sound.

The young Nina Stemme is a bit warmer-toned than many sopranos who sing Isolde, and that, in concert with a vocal and interpretive precision every bit Domingo's match, is more welcome in this role than one who cut his teeth on Nilsson's titanium sound would ever have thought—and Stemme has a liquidness Nilsson never had. Suddenly, and barely a year after Deborah Voigt's excellent Vienna Isolde, Stemme has defined for herself an entirely new category. I now can think of no one else I'd rather hear sing this part.

The same goes for René Pape as King Marke. This crucial role is small, and too often even the best basses seem to pick a single emotion—grief, sorrow, sadness, gentle reproach, anger at trust betrayed—and color Marke's entire narration in that hue. Pape's palette holds them all, and he is a master of the telling tonal tint, the expressive phrasing. His singing qua singing is absolutely gorgeous—no syllable goes uninterpreted, nothing is phoned in. But this is true of everyone here.

The original versions of the 12th-century Tristan legend's characters—Tristram, Yseult, and the characters Wagner conflated into Kurwenal—were all in their late teens, and Olaf Bär's feisty, terrier-like Kurwenal sounds it. The bottom of the voice is not as full or as steady as it might be, but that is my only vocal quibble with this recording. The Young Sailor is the rising superstar tenor Rolando Villazón, who makes of the brief song that opens Act I not the usual slow, melancholy elegy (which runs counter to the text), but the crowing of a young stud feeling for the first time his full virility, passion, and voice, and trying to fill all outdoors with them. Even the light-voiced Ian Bostridge is ideally cast and coached as the Shepherd—after two acts full of huge, world-class voices singing at the limits of their abilities, the Shepherd's brief interlude of relative calm at the beginning of Act III is delicious respite before we are plunged again into Tristan's living hell.

After a shaky start in the Act I prelude, which does not entirely cohere until about halfway through, Pappano's grasp of Wagner's most perfect and most modernist score—with which Western music continues to come to terms a century and a half later—never again falters. Pappano seems more versed than most conductors in the dramatic functions of Tristan's leitmotifs, so much more subtle and dovetailing than those of the Ring. This makes his reading of the opera more musically revealing as well. Again and again I heard familiar motifs, either rising from the low strings and brasses or emerging from supporting woodwind parts, in places I had never noticed them before. Almost always these were the motifs relating to night, death, and the love potion's fatal magic; conscious or not, Pappano's interpretation emphasizes that it is only the lovers' mutual desire for death that simultaneously engenders and dooms their love.

The sound of Abbey Road's Studio 1 is warm and rich, deep and immense, with sweet highs and little spotlighting. The session photos show Domingo and Stemme singing from the middle of the orchestra, and Domingo is very occasionally half buried in the sound—though only in the most "natural" way. The set includes a free DVD-Video disc containing the entire opera in 5.1-channel surround with onscreen libretto and translations, for those so equipped. The text is easily readable, with an excellent essay by Wagner scholar Barry Millington.

For 40 years, the Nilsson-Windgassen-Böhm recording from the 1966 Bayreuth Festival has been the recording of Tristan und Isolde against which all others have been compared and found wanting by most critics, including this one. In the December 2004 Stereophile, I concluded my review of the recent Christian Thielemann recording, with Deborah Voigt and Thomas Moser, with "One of these every 40 years or so seems about right." Now we have two such. This new one might be the best ever, and for a long time to come.

In their promotion of this recording, EMI hints darkly that it might be "the last" studio recording of a full-length Wagner opera. Even had this been true—Naxos has since disproved it by releasing their own new studio Tristan—I could have been grateful for this recording for the rest of my life. It is the Tristan I have always wanted to hear.—Richard Lehnert

- Log in or register to post comments