| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

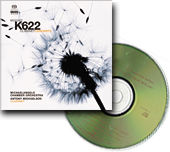

Project K622

The upbeat is the most magic moment in classical music making. Before the conductor brings down his baton for the downbeat, anything and everything are possible in the musical journey that is about to begin. And the upbeat to Mozart's sublime Clarinet Concerto that conductor Robert Bailey was about to give in London's Henry Wood Hall last November gave me an extra frisson—as producer of the recording sessions, I would have to pronounce instant judgment on everything I was about to hear.

Talk about pressure. It's hard enough for a critic to be right, even with all the benefit of hindsight the writing process affords. But to be right in real time, with a conductor, a soloist, an engineer, and 30 of London's leading classical musicians, all of whom have forgotten more about music than I ever learned, waiting for my critical voice to emerge from the talkback speaker, is a pretty good definition of big-time stress overload.

Talk about pressure. It's hard enough for a critic to be right, even with all the benefit of hindsight the writing process affords. But to be right in real time, with a conductor, a soloist, an engineer, and 30 of London's leading classical musicians, all of whom have forgotten more about music than I ever learned, waiting for my critical voice to emerge from the talkback speaker, is a pretty good definition of big-time stress overload.

The first time I asked Robert to have the orchestra repeat a passage—in this case, the ensemble wasn't quite together and the intonation seemed a bit sour—he asked me if I was sure. I sucked in my gut, crossed my fingers, knocked on wood, rubbed my good-luck talisman, and crossed my heart. Then I flicked the mike switch on and said, "Yes, maestro, measures 72 through 74 were a little untidy in the violins. Could we take it again?"

But I'm getting ahead of myself...

Michaelson & Mozart

Back in 1999, I had invited Musical Fidelity's Antony Michaelson to Blue Heaven Studios in Kansas to record the Brahms and Mozart Clarinet Quintets. The resultant Stereophile CD, Mosaic has sold consistently since its release, and is still available from the secure "Recordings" page on the Stereophile website. Antony and I had kept in touch about possible follow-ups to Mosaic, so when he called me in the summer of 2003 about producing a recording he was planning of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto, K.622, I didn't need much in the way of persuasion, particularly when he told me that we were going to work with recording engineer Tony Faulkner.

I've known Tony since the late 1970s, when he was working for English audio writer Angus McKenzie and I was a lowly reporter for English magazine Hi-Fi News. I have followed Tony's subsequent rise to preeminence in the classical recording community since those early days when we both took part in blind listening tests for reviewer Martin Colloms.

I asked Antony who the band was going to be.

"The Michaelangelo Chamber Orchestra."

I was none the wiser.

Antony explained: One of the beauties of recording in London—unlike, say, Kansas—is that it is home to some of the world's finest session musicians. Concertmaster Adrian Levine had "fixed" a Mozartean orchestra consisting of eight first violins, six second violins, four violas, four cellos, and two basses, with two each of flutes, bassoons, and horns, almost all of whom are principals or front-desk players in the London orchestras. Two notable exceptions would be two American musicians—violinist Kathy Andrew and cellist Judith Serkin—who, like Adrian Levine, had played for me in the Mosaic quintet. (Sadly, Mosaic violist Stephen Tees had another gig that day.)

With an ensemble of this caliber—and assuming Antony's nerves held up—it would be possible to get the work down in three two-hour sessions. Antony had worked with Robert Bailey and an earlier incarnation of the Michaelangelo [sic] orchestra for a 1998 recording of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto, released as a CD on the Musical Fidelity label (MF018). I asked Antony why he felt it time to return to the concerto.

"I have learned a lot about the clarinet since I started studying with Dame Thea King," he explained. "I also feel I have gained a deeper understanding of the Mozart in the last five years. The music matures in your unconsciousness. Suddenly, I will hear how a phrase should be shaped. It's an ongoing process of development—as you get older, the more you hear, the more you understand what the music's about."

Antony also explained that not only did he want the project recorded in DSD for release as a Super Audio CD, he want to run analog tape for an LP release. That way, audiophiles could choose between a "pure" analog release and a "pure" two-channel SACD. Why not a multichannel SACD? Antony snorted. "I think multichannel is a complete waste of time. My experience of music and music reproduction is that two channels are, for me at least, about right. Three channels offer a marginal improvement over two, and five channels are a marginal improvement on a marginal improvement. Multichannel is okay for sound effects, but it is of no significance for music whatsoever!"

Antony also explained that not only did he want the project recorded in DSD for release as a Super Audio CD, he want to run analog tape for an LP release. That way, audiophiles could choose between a "pure" analog release and a "pure" two-channel SACD. Why not a multichannel SACD? Antony snorted. "I think multichannel is a complete waste of time. My experience of music and music reproduction is that two channels are, for me at least, about right. Three channels offer a marginal improvement over two, and five channels are a marginal improvement on a marginal improvement. Multichannel is okay for sound effects, but it is of no significance for music whatsoever!"

But he did note that the SACD would be a hybrid. Not only would it carry the DSD recording, its hi-rez layer would include a DSD dub from the analog master tape, while the "Red Book" layer would contain two versions of the recording: a 16-bit/44.1kHz PCM version downsampled from the DSD master, and a straight PCM transfer from the analog master. That way, audiophiles would be able to compare all four formats and reach their own conclusions about which best preserved the musical message. (There is also a CD release, available from Musical Fidelity in the UK.)

- Log in or register to post comments