| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

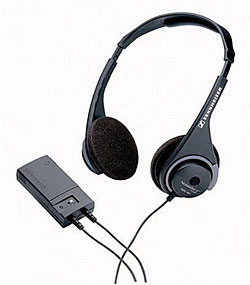

Sennheiser HDC 451 Noiseguard headphones

I was cruising at 36,000 feet, totally relaxed, listening to Richard Thompson. Looking down at my lap, I caught sight of a little box with a glowing green light. Switching off this light was like turning on the noise—the 767 was roaring like a locomotive and the ambient sound hit me like a fist. Thompson's crisp Celtic chordings turned mushy, undetailed, and dull. I felt weary. Whoa, I wouldn't do that again if I were you, laddie! I fumbled for the switch and reactivated the NoiseGuard circuitry on my Sennheiser HDC 451 noise-canceling headsets. Thompson's guitar rang out clearly, the airplane quieted to sound like an S-class Benz, and I relaxed into a calm reverie with only one worry clouding my contentment. But I patted my pocket: yup, still two cognacs left. Everything would be all right.

Noise annoys

Noise annoys

When I recently visited Sennheiser's manufacturing facilities in Wennebostel, Germany, I learned that the firm has long been a leader in avionic communication devices. At first I figured that pilots and air-traffic controllers just recognize a quality headset when they hear one—but there's a little more to it. Noise in their high-stress environment isn't merely an annoyance—it causes fatigue, masks vital information, and can lead to permanent hearing damage.

So Sennheiser set out to combat noise and its side effects by actually canceling it. Their Noiseguard circuitry incorporates a microphone which inverts the polarity of ambient noise 180° and feeds it back into the headset diaphragms, resulting in a drastic reduction in the perceived levels of that noise. While at the factory, we got to don various models of their aviation communication rigs while they played tapes recorded in different aircraft at real-life loudness levels. From single-engine Cessna to fighter jet, the headgear did the job—turn on the Noiseguard and suddenly we could hear what our colleagues were saying, clearly and without strain. Pretty darned impressive, especially when you consider that the number-one cause of in-air accidents is miscommunication. I may never get on a plane again without confirming that the flight-deck crew is wearing Sennheisers—I don't want to be a statistic!

On our way to the airport the next day, Sennheiser's John Bevier passed out samples of Sennheiser's HDC 451, a consumer model that incorporates Noiseguard into a pair of dynamic Open-Aire headsets like the ones commonly used with quality portables. Set in the middle of the connecting cable is a box just large enough to hold two AA batteries. One side of the box sports a sliding switch and an LED, the other a belt clip. Sliding the switch activates the Noiseguard and illuminates the LED. Battery life is given as 80 hours. The only-slightly-oversized motor housings on the earpieces contain discreet pea-sized screens—these are the microphones.

Cum on, feel the noyze

A busload of audio critics just received free headphones. Quick! What do you think happened next? To a one, we all either bum-rushed our luggage for our portables or stood there clicking the circuit on and off, giggling. I did both. Turning on the noise-canceling circuitry without music playing does feel a little weird. First, it causes a slight pressure on your eardrums. After all, that is what it's doing—creating a signal just as loud as the noise in order to cancel it. This is not uncomfortable, but I found myself swallowing more, as if to equalize pressure. Second, from 400Hz to 1kHz the noise does fall away—a measured 10dB reduction. What I found interesting was that the reduced-noise state doesn't feel unnatural; turning the circuitry off and reemerging into the world of noise—that feels unnatural. It's like turning the noise on. Who'd want to do that? Not me. In those first few minutes I swore a solemn vow to never take off my 451s.

I turned to tell my wife that she was going to have to live with a man permanently attached to a pair of headphones—less of an adjustment than you'd think, actually. She removed her 451s to catch what I was saying and winced at the roar of the bus's diesel. She put her 'phones back on and whispered, "Wow, I hear you so much more clearly with these on!" It was true; an added benefit was the extent to which speech and other essential sounds were able to penetrate. On the plane, when our stewardess gave her safety presentation, we put our 451s on to hear her better. We were getting hooked.

Listening to music through the 451s is enjoyable, too. I consider them several steps above the standard Walkperson headphone, although sonically they're no match for the Sennheiser HD-580s, Etymotic ER-4Ses, or Stax Lambda Pros that rightly inhabit Class A of our "Recommended Components." In fact, it's a little hard to get a handle on how good they are at just playing music. Put them on without activating the NoiseGuard circuitry and they don't, frankly, sound very much different from the bulk of Walkperson headsets. Grado's SR 60s ($60) sound considerably better, I think. But turn on the circuitry and the 451s immediately improve in clarity, articulation, and freedom from fatigue-producing artifacts. Perhaps they sound a touch too bright, but I start to mistrust my sonic judgments around NoiseGuard—after all, I'm the guy who said that turning off the device felt like you were turning on the roar of the world—very confusing, that. Is it too bright with the circuit on, or has the noise reduction subjectively brought out detail otherwise masked? I keep turning it on and off looking for an answer.

Since I enjoy listening critically while flying—enough to lug around a complete HeadRoom system—I'll probably continue to employ my Etymotics for in-flight listening. After all, their in-the-ear isolation renders 24dB of noise reduction and greater frequency range to boot. But not everybody listens to music the way I do while traveling. For listening to the in-flight programs, or for watching the featured film, the 451s are great! In fact, Sennheiser includes an adaptor for that dorky dual-mono plug that the airlines have designed specifically to keep you from using your own headsets.

Here's a little hint for you even if you don't listen to music: buy a pair of HDC 451s to listen to nothing with. "Buy a headphone and not even plug it in?" you ask. It sounds crazy, but you'll land feeling so relaxed without having had all that jet-roar pounding at your ears (footnote 1), Or use 'em for sleeping—while I'm not sure there's such a thing as quality sleep on an airplane, you'll get much better rest with a pair of these.

You might find these handy if you transcribe tapes a lot, as I do when writing up interviews. They've become my favorite tool for that—I strain less to make out details and therefore work much faster.

I took them into the subway back when I lived in New York. A lot of subway noise is below 400Hz, but even so, they made my trips a lot more enjoyable. They also deterred a certain number of those annoying subway conversations with crazy people—even madmen know better than to talk to someone with headphones on.

Fly the quiet skies...

The Sennheiser HDC 451 NoiseGuard Mobile headphones are not, I suppose, for everyone. Business travelers and other unfortunates who seem to live on aircraft should definitely consider buying a pair, if only to get a good flight's sleep. If they also get a chance to enjoy some high-quality music, or better comprehend an in-flight movie, so much the better. If you work in one of those open-plan offices or have your desk under the fan—or if you generally find yourself tired from constantly battling a noisy environment—then the HDC 451s may actually purchase you some peace. God knows, not many products offer that.

Footnote 1: I took the '451s with me on a recent trip to Europe. While I found the sound quality was nothing to fax home about, particularly when compared with the Grado SR 125s that I stuck in the Headroom Supreme's output jack for music listening—great cans, these—the noise cancellation with no music playing was addictive. One thing puzzled me psychoacoustically: The effect of the headphones seemed to be that while the noise within my head was very much lower in level, I was still aware of low-frequency noise coming from the sides. I guess that the cancellation is very much more efficient with common-mode noise, hence this weird effect. Or, perhaps, the cancellation of upper-bass and midrange noise unmasked the lower-frequency component.—John Atkinson

- Log in or register to post comments