| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Verity Audio Sarastro II loudspeaker Page 2

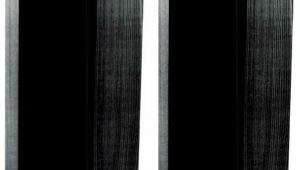

It's possible that my listening space—the living room of a Victorian brownstone—might not be ideally suited to the Sarastros. It has 10'-high ceilings, it's quite long (20' and connecting to a library and dining room that together add another 25'), and there's a lot of diffusing asymmetries (an oval window bay, filigree on the ceiling, mahogany trim and shutters, plush furniture, wooden bookcases, etc.). But it's also just 12' wide, and—even though there's a large opening to a stairway on one side of the room—the woofers would probably like another 2–3' of breathing space. For this reason, I also auditioned the speakers after they had been set-up by John Quick in John Atkinson's listening room, which measures 24' by 15' with a 7' 10" ceiling. I report briefly on the differences at the end of this review.

Sound

Even in my less than ideal space, the Sarastro IIs sounded terrific. Were they twice as good as the Parsifal Ovations? Who can measure such matters? But the Sarastro IIs did take recorded music to a level of refinement, detail, and—what's the phrase...oh yes, high fidelity—that I hadn't heard in my system before.

The first thing I noticed was how airy and free-flowing the music sounded. When I reviewed the Parsifal Ovations for The Abso!ute Sound three years ago, I wrote that their 1" soft-dome tweeters sounded so extended that I could have sworn they were ribbons. After hearing the Sarastro II's tweeter, which really is a ribbon, I guess what I'd swear is not to exaggerate from now on. In retrospect, what I found remarkable about the Ovation was, yes, its extension of the highs, but even more, how smoothly those highs were extended, and how seamlessly they integrated with the midrange. The Sarastro II sounded still more extended, at least as coherent, and—here's where it most differed from the Ovation—fast as lightning (not that the Ovation is a sluggard).

The first thing I noticed was how airy and free-flowing the music sounded. When I reviewed the Parsifal Ovations for The Abso!ute Sound three years ago, I wrote that their 1" soft-dome tweeters sounded so extended that I could have sworn they were ribbons. After hearing the Sarastro II's tweeter, which really is a ribbon, I guess what I'd swear is not to exaggerate from now on. In retrospect, what I found remarkable about the Ovation was, yes, its extension of the highs, but even more, how smoothly those highs were extended, and how seamlessly they integrated with the midrange. The Sarastro II sounded still more extended, at least as coherent, and—here's where it most differed from the Ovation—fast as lightning (not that the Ovation is a sluggard).

A brief but pertinent digression: When audiophiles talk about "highs," we're not talking about the higher notes of any particular instrument's range, but rather about harmonic overtones, and the wisps and whispers that distinguish, say, an alto from a tenor sax (even when playing the same pitch), or a violin from a viola, or the ambience of Carnegie Hall from that of another hall of similar but somewhat different acoustic. A speaker, and especially its tweeter, must be extremely fast and agile to reproduce those subtle signals—and at this, the Sarastro II was a champ.

On Bill Evans' Waltz for Debby (SACD, Analogue Productions CAPJ 9399 SA; LP, AAPJ 09), Paul Motian's cymbals sizzled more briskly than I'd heard in the hundreds of times I'd heard this record before; ditto for his crisp brushwork on the snare.

On Gene Bertoncini's Quiet Now (SACD, Ambient CD 005), a lovely jazz solo-guitar album, I could hear the most minute fingerwork, the faint slap echo on the wood, the effervescent fizz rising into the air when Bertoncini strums a high note, even a bit of the oval shape of the sounds blooming forth from the acoustic guitar's hole. (For an amazing display of fast acoustic guitar work, check out Paul Brady's energetic solo on "Arthur McBride," from the CD Andy Irvine/Paul Brady, Green Linnet GLCD 3006, if you can find it.)

At the start of Duke Ellington's "Mood Indigo," from Masterpieces by Ellington (CD, Columbia/Legacy CK 87143), the horns play the melody in unison, and although this album was recorded in mono, I could clearly distinguish each instrument: clarinet, sax, trumpet. I could do the same with the unison woodwinds, accordion, and wordless vocalizing at the beginning of Maria Schneider's modern stereo recording, Sky Blue (CD, ArtistShare AS0065).

These overtones weren't merely suggested; they were captured in their full dynamics. In Paul Simon's "Jonah," from disc 2—the underrated "middle period"—of his 1964–1993 (3 CDs, Warner Bros. 45494-2), someone plays a hand drum way off to the left of the left speaker. I'm impressed when a speaker (or amp, or whatever) can place that drum way to the left and can let me hear a bit of the drumhead's texture. The Sarastro IIs did that—and let me know that the percussionist gave the drum head a real smack. That eye-blinking transient was something I hadn't heard before.

From top to bottom, instruments sounded like themselves in tone, timbre, dynamics, and (to the degree the recording captured it) size—even when many different instruments were playing simultaneously. On Nicholas McGegan and the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra's rendition of the Concerto in F, RV 569, from Vivaldi for Diverse Instruments (CD, Reference RR-77CD), the blurting of the bassoon, the gritty resonance of the harpsichord, the sputtering of the valveless natural horns, the astringent warmth of the gut-strung violins—all were clear, distinct, and enmeshed in a gorgeous acoustic bloom.

The Veritys gave electric rock a good workout too. The crunching at the start of Radiohead's In Rainbows (CD, ATO/Red 0001) was, well, extremely crunchy. (What is that sound?) The bass drum made me blink. The guitars screamed. And against all this well-pitched grunge, the voice was clear, upfront, even intelligible.

In his review of the Sarastro I, my friend and colleague Michael Fremer complained that, though the SPL meter said otherwise, the speakers never sounded loud enough. "I was never kicked by a kick drum or seared by squealing...guitars," he wrote. MF may have a more demanding standard of loudness than I, but I didn't have a problem with the IIs. To me, the key in capturing loudness isn't so much the decibel level as whether the music swells as it gets louder—whether it expands in volume, in the spatial sense of the word. The Sarastro II got that right—whether it was the swelling of the strings in Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony's performance of Mahler's Symphony 9 (SACD, SFSO 821936-0007-2), or Radiohead's kick drum and wailing guitars.

This sense of volume has as much to do with dynamic contrast as with dynamic range—the density of gradations between loud and soft, not just the vastness of difference between the loudest and softest sounds. Fine dynamic contrasts unveil the human source behind the music—the pedals of a piano, a violinist's variations in bowing, the slight opening or tightening of a singer's vocal cords. In this realm, the Sarastro II was as agile as anything I've heard. In this sense, Fremer's broader point about the original Sarastro holds equally for the II: it was "more about touch, texture, resolution, and context than about slam and throwing me back in my seat."

But such agility is for naught if a speaker doesn't get the inner, or textural, detail of an instrument just right, and this was another of the Sarastro II's strong points. I don't know how many times I've listened to David Zinman and the London Sinofonietta's recording of GÛrecki's Symphony 3 (CD, Elektra Nonesuch 79282-2), but before the Sarastro IIs, I don't think I'd ever heard, at around the 15-minute mark, the pianist gently playing behind soprano Dawn Upshaw. Another reference disc I've played over and over is jazz pianist Don Pullen's Sacred Common Ground (CD, Blue Note CDP 8 32800 2), but I'd never heard his piano sound so luminous—not an artificial glow, but a coherent reproduction of the instrument's percussive hammers, warm wood, and Pullen's distinctive touch.

Nor was there anything to complain about when it came to the Sarastro IIs' renderings of space. Their soundstage was as wide and deep and high, the images as solidly 3-D, as the recording permitted.

I could continue this sonic checklist, except that it would undermine what was most impressive about the Sarastro IIs: the sheer, unfatiguing pleasure of listening to them. With something like "Nuages," from James Carter's Chasin' the Gypsy (CD, Atlantic 83304-2), other speakers have impressed me with how well they capture the strumming guitars, the snapping percussion, the ringing triangles, the fast snare-drum rolls, and so on. Through the Sarastro IIs I heard all that, but what made my head spin was the music as a whole. My reaction wasn't so much "Listen to how real that drum sounds" but rather "Listen to how rhythmic that drummer is," or "Listen to how tight this band is." Listening to a slew of well-made recordings, I heard all the details that thrill us audiophiles, but none of them stood out; all were naturally woven into the music.

What about the bass? First, it was very tuneful, with no one-note thumping—I could follow with no strain bass lines that were otherwise buried in the mix. But there was some ripeness, a bit of a boom, at around 100Hz. The length of a 100Hz soundwave is about 12', the same as my room's width. I think the boom was the woofers—which are designed to couple with the room—exciting the primary room-width mode. Unlike most bass booms, this slight boom didn't annoy me because it didn't obscure any detail elsewhere in the audioband. Nor am I sure that, in a bigger room, it would even be present. But it's present in mine. (Hearing the speakers in JA's room may solve this mystery.)

Against the YGA Anat Reference Professional

Apart from that narrow bass boomlet, the Sarastro II was on the slightly warm side of neutral. I like this; if speakers are to err (and they always do), I'd much rather they be a little warm than a little cool, as long as they're still fast and detailed—which the Sarastro II was. But because I'd never reviewed speakers so expensive, I went to Wes Phillips' house to hear a pair of speakers he was reviewing for Stereophile's March 2009 issue, the YG Acoustics Anat Reference Professional, which have enclosures of solid aluminum and retail for $107,000/pair.

On first hearing, I thought the YGAs sounded a bit metallic; after a while, I realized that they were as close to absolutely neutral as perhaps any speakers I'd ever heard. I'd grown accustomed to the "woodiness" of most speakers, even of very rigid models such as those made by Verity Audio. Listening to the YGAs reminded me that, however pleasant, wood warmth is still a coloration. Of course, it's also worth noting that the Anat Reference Professional costs nearly three times as much as the Sarastro II. But by any other standard—even that of $40,000/pair speakers—the Verity Audio Sarastro II is pretty damn neutral—very revealing and yet easy on the ears.

Conclusion

After hearing these speakers in John Atkinson's room, (much wider and a bit less warm than mine), I would reemphasize the point: The Sarastros won't show all their stuff unless your room is at least 15' wide, and even then you need a trained dealer to help with set-up. That said, even at John's place, there was a ripeness—bass tones got a bit bigger and more reverberant—around the crossover point between the woofer and the midrange. It's a minor thing; if it hadn't been more obvious in my own room (and even there it wasn't anything close to prominent), I wouldn't be making so much of it. But it's there. If you can live with that touch of character, definitely give Verity's Sarastro II a listen: it's musically involving and punctiliously precise.

- Log in or register to post comments